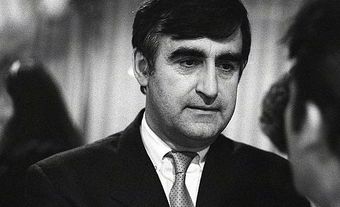

Background and Education

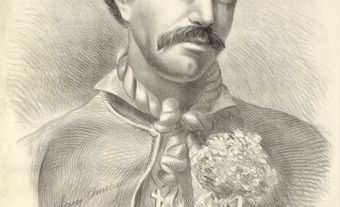

Alfred Évanturel was born in Quebec City on 31 August 1846 into a middle-upper-class family with ties to the intellectuals of the Parti rouge. His father, François Évanturel, was a member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for the riding of Quebec City from 1855 to 1857 and from 1861 to 1867, and then Minister of Agriculture and Statistics in the cabinet formed by John Sandfield MacDonald and Louis-Victor Sicotte (1862-1863). François Évanturel supported Confederation unenthusiastically, reassured only by the establishment of Quebec as a French-Canadian province to which authority in the social and cultural spheres would devolve.

François Évanturel’s son Alfred studied at the Séminaire de Québec and first expressed his views publicly in that institution’s student newspaper. He received his law degree from Université Laval in 1868, was called to the Quebec City Bar in January 1870 and worked for a few years as a partner with Thomas McCord, Crown attorney and Clerk of the Quebec Legislative Assembly. In the winter of 1874, Alfred Évanturel accepted a position in the office of the federal Minister of Public Works and moved to Ottawa, where his wife, Louisa Lee, gave birth to their two children, Stella (1876) and Gustave (1878).

Professional and Political Career

In the last quarter of the 19th century, thousands of French Canadians migrated to Ontario, where they settled in the United Counties of Prescott and Russell in the eastern part of the province or joined the federal public service. As of the Canadian Census of 1881, there were 103,000 French Canadians in Ontario. They accounted for 64 % of the population of Prescott and one-quarter of the population of Ottawa. In 1875, Alfred Évanturel became a trustee of the Ottawa Separate School Board and began working with the Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa. In 1878, he was called to the Provincial Court in L’Orignal, Ontario to defend a unilingual francophone client, and he considered making a career there. He also gained notice for his speech at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day celebrations in L’Orignal in June 1880, exhorting French-Canadians to remain true to their roots and form a local voice to demand greater respect from the English Protestant majority.

With longer-range goals in mind, Alfred Évanturel began practicing general law in Saint-Victor-d’Alfred in Prescott in spring 1882. Well aware that the people of Prescott had been voting for the Conservative Party for many years, he ran as a moderate Conservative candidate in the provincial elections of 1883, but was defeated. He continued to practice law and took advantage of francophone discontent surrounding the hanging of Louis Riel to launch a “red” weekly newspaper, L’Interprète, in August 1886.

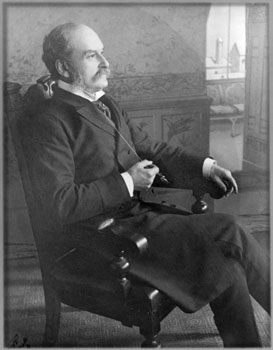

In the provincial elections of 28 December 1886, Évanturel was elected Liberal MLA for the riding of Prescott. His newspaper received hundreds of dollars’ worth of advertising from the Quebec Liberal Party. He supported the positions of the Liberal Party in Ottawa, Toronto and Quebec City and linked the Conservatives with the most fanatical actions of the Orange Order. Called upon to defend bilingual schools in the Ontario legislature in March 1887, he underscored the Liberals’ desire both to ensure that these schools provided good instruction in English and to improve the training of French-Canadian schoolteachers (see Ontario Schools Question). To secure the support of Catholic voters, Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat defended the sharing of powers and respect for religious and ethnic minorities. Thus, the government that Alfred Évanturel was joining had no intention of triggering school crises like those in New Brunswick or Manitoba (see New Brunswick Schools Question and Manitoba Schools Question).

But Premier Mowat had to respond to the nervousness of some voters who feared that Ontario was being “invaded” by French-Canadian migrants. Alfred Évanturel’s correspondence of that time highlights his interest in strengthening the bilingual schools in his riding and his work with Ontario Minister of Education George Ross, who consulted Évanturel in developing educational policy. As a backbencher in the Legislative Assembly, Évanturel was called upon to support the government’s position. He reminded French-Canadians of their duty of loyalty to the British Crown and their desire to build a new nation “between two great elements”, as he put it so well in March 1887. In January 1890, Minister Ross opened the first bilingual model school in Plantagenet, Ontario. The school regulations issued in winter 1890 also required that bilingual schools teach more subjects in English, when possible.

Premier Mowat presented Évanturel as a bridge between the “two great elements” of Canada at an interprovincial conference in 1887 and asked him to assume the task of securing the loyalty of Ontario’s Catholic and French-Canadian voters. Ever the good soldier, Évanturel agreed, but also suggested in the pages of L’Interprète that he be appointed to the provincial cabinet. The following year, he expressed this desire to George Ross, who explained to him that there was already a Catholic minister in the cabinet. Wilfrid Laurier, then leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, also asked Évanturel to be patient, because what he wanted would “happen on its own”. Évanturel continued his tours of the majority of the “French groups of Ontario” and English-speaking Catholics during the illness of Minister Christopher Fraser, himself a defender of the Catholic minority. The Liberals also called on Évanturel’s oratorical skills at federal and Québec election campaign rallies.

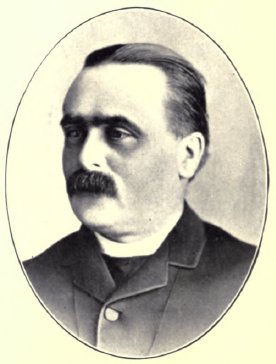

Certainly, English-speaking Protestants and Catholics were represented in the provincial cabinet of Honoré Mercier in Quebec, but Évanturel’s attempts to secure an Ontario cabinet position by threatening to resign from the legislature and run as a federal Liberal candidate, and his intimations that his supporters in Prescott would not re-elect him unless he was appointed to cabinet, were far-fetched and ineffective. However, when Laurier became prime minister after the federal election of June 1896, everything changed. He wrote the new Liberal premier of Ontario, Arthur Hardy, pressuring him to make Évanturel a minister: “From the point of view of Dominion politics, such a step… would be an offset to the [Manitoba] School question in showing the liberality of our Ontario friends to their French brothers.” Hardy hesitated at first, but in 1897 named Évanturel Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, a position that he held until 1902.

Although the French Canadian newspapers rejoiced over this appointment, Évanturel’s role remained largely ceremonial. He represented Ontario at the Exposition universelle de Paris, and his correspondence indicates that he limited his interventions to the school question and to requests for patronage. In 1899, Premier Hardy authorized Ontario’s Catholic school boards to collect taxes for “post-elementary” schools (grades 9 and 10) in rural areas that had no public high schools. Since French Canadians lived largely in rural areas, this was an important step in developing a Franco-Ontarian education system. At the time, there were some 200,000 French Canadians in Ontario. They represented 40% of Ontario’s Catholics, constituted majorities in several localities in eastern and northeastern Ontario, and founded several hundred parishes, schools and associations. As historian Gaétan Gervais has put it, they now formed a “viable” community.

In fall 1904, Alfred Évanturel was at last rewarded with an appointment as minister without portfolio, but he did not get to enjoy it for long. In the provincial elections of January 1905, he was defeated along with the government of which he was a part. Évanturel now hoped to sit as a “French-speaking senator” for Ontario. Although Laurier was favourable to the idea in 1902, by 1907 events had conspired to make other candidates (such as Napoléon Belcourt) a more strategic choice. Évanturel expressed his anger and disappointment to Laurier, who offered him the position of Clerk of the Senate of Canada as a consolation in December 1907. By then, Évanturel was ill. He held the position for less than a year and died on 15 November 1908.

Legacy

Alfred Évanturel’s son, Gustave Évanturel, continued the family tradition of political involvement in French-speaking Ontario. In the provincial elections of 1911, he was elected Liberal MLA for Prescott, and when the new Conservative government issued Regulation 17 in 1912, he fought against it.

The Township of Évanturel, in eastern Ontario, is named in Alfred Évanturel’s honour. Since 2005, the Prescott-Russell chapter of the Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario has been presenting the Alfred Évanturel Award each year to honour local elected officials who have contributed to the development of the francophone community—a recognition, in some sense, of Alfred Évanturel’s unlikely yet courageous struggle to ensure that the Franco-Ontarian community would endure.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom