Craft Unionism

Craft unionism, a form of labour organization developed to promote and defend the interests of skilled workers (variously known as artisans, mechanics, craftsmen and tradesmen). Craft skills have always involved both manual dexterity and conceptual abilities; their value and scarcity have given such workers considerable power in the workplace. Craft unions sought to maintain that power by controlling training, regulating the work process, and insisting that only members should practise any particular trade. Pride and independence bred a spirit of solidarity and led to Canada's first labour movement.

A full-fledged guild system protecting traditional crafts on the British and European model never developed in British North America. Men were generally expected to serve lengthy apprenticeships before becoming fully qualified practitioners or journeymen. Craft unions first appeared early in the 19th century when some journeymen began to recognize their common interests. By the 1830s journeymen shipwrights, printers, tailors, stonecutters, carpenters and others had formed unions and had even launched a few strikes for higher wages and improved working conditions. Many of these unions also established mutual-benefit funds to help their members cope with sickness, accident or death.

The first craft unions united skilled workers in single communities but, beginning in the 1850s, craftsmen began to affiliate with larger organizations. At first British workers established local branches of the unions they had left behind, like the Amalgamated Society of Engineers or the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners. But skilled workers in Canada increasingly linked their local unions to such new American craft unions as the Iron Molders' Union and the National Typographical Union, which were organizing workers across the continent - a development that reflected the growing tendency of workers to "tramp" around North America in search of work. This "international unionism" was intended to establish common standards of employment across the continent. Many craft unions in Québec, however, refused to join the internationals because of their insensitivity to French language and culture.

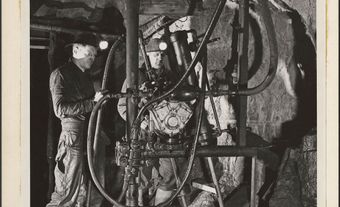

When Canada's Industrialization began after 1850, many employers attempted to erode craft skills by subdividing tasks among less-skilled workers and by introducing new machinery. By WWI these changes had brought mass production and "scientific" management. Craftsmen used their unions to resist any changes they believed would disrupt work routines, lower wages or threaten unemployment. For the practice of each craft the unions developed much tighter rules and regulations, which employers were expected to accept as a condition of hiring skilled workmen. These new rules governed such matters as apprenticeship, daily workload, hours of labour and tools of the trade.

Many employers resisted these restrictions on their unbridled control, and craft unionists fought hundreds of bitter strikes in the half century before 1920. Craftsmen were often the most vigorous and articulate critics of industrialization, which they believed was degrading the worker and his job. By the 1920s industrialists had driven craft unions out of most workplaces and had transformed work processes so thoroughly that they no longer relied on many scarce handicraft skills. It was only in the printing and construction industries that craft unionism survived with any vitality.

Craft unions had a long history of uniting across occupational lines to form labour councils in individual communities, at the national level in the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, and across the continent in the American Federation of Labor. Many craftsmen became uneasy, however, about the rise of Industrial Unionism, which would unite all workers in a single industry regardless of skill and might dilute the skilled workers' power. In 1919 they opposed the One Big Union, which promoted the new form of industrial organization, and in the 1930s set themselves against the American-based Congress of Industrial Organizations. In 1939 the TLC succumbed to AFL pressure and ousted CIO unions from its ranks. Some craft unions (eg, machinists' and carpenters' unions) nonetheless broadened their membership base gradually to include workers in mass production and related industries.

In Québec craft and industrial unions had co-existed inside the Canadian Catholic Confederation of Labour since 1921. Elsewhere, these 2 streams were reunited in the new Canadian Labour Congress. The friction did not disappear, however, and during the 1970s disputes over craft-union jurisdictions and autonomy of Canadian unions from international headquarters prompted several construction unions to withhold their CLC dues. Suspended in 1981, the following year these craft unions formed a new national organization, the Canadian Federation of Labour,giving craft unionism once again a distinct identity.

See also Working-Class History.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom