This article was originally published in Maclean’s magazine on March 23, 1998. Partner content is not updated.

They are lining up to meet her in the flesh. Hundreds of broadcasters, delegates to a country radio conference, have gathered for a party at the new Planet Hollywood in Nashville.

They are lining up to meet her in the flesh. Hundreds of broadcasters, delegates to a country radio conference, have gathered for a party at the new Planet Hollywood in Nashville. In a room ringed with buffet tables, some queue up for Cajun shrimp, but the major feeding frenzy is around Canadian country star Shania Twain. She is not singing; she is signing autographs and posing for snapshots while a video of her song Don't Be Stupid plays on the wall behind her. The broadcasters so eager to meet her are professional fans, fans with influence. And Twain greets them with professional warmth. A hundred handshakes. A hundred autographs. A hundred point-and-shoot smiles. And, with each click of the shutter, a hundred strange hands clasped around her famous midriff. Every so often, like a boxer rehydrating between rounds, Twain turns to her makeup artist, Daisy, who holds up a bottle of water for her to sip through a straw. Finally, after more than an hour, Twain's handlers whisk her upstairs. In the elevator, the star holds out her hands. Daisy, who knows the drill, produces some wet wipes and scrubs them clean.

Later, in a roped-off VIP area upstairs, Twain sits for a moment before resuming the "meet and greet" ritual with another echelon of fandom - employees of her own record company. Does it not all start to seem absurd after a while? Twain fields the question with a puzzled look. "Not really," she says. "It's just part of it now. And people who want to meet you usually get some pleasure out it. It's nice. It's a nice exchange."

Nice. For the reigning queen of country music, playing the girl next door to throngs of strangers has become second nature. Country singers, like TV soap stars and politicians, are still expected to service the fan base in person. Up close, Shania Twain loses none of her radiance; she has the sort of star power that people expect from royalty. And part of the magic is a life story that reads like a fairy tale - Cinderella meets Bambi in the Canadian bush. A country girl from Timmins, Ont., is raised dirt poor, starts performing in bars as a child, loses her parents at 22 when their car collides with a logging truck, sings to support her three teenage siblings, then finds her prince - reclusive rock producer Robert John (Mutt) Lange - who gives her a studio kiss of stardom and a 2.5-carat diamond.

It is a story that occasionally threatens to veer into melodrama. Twain has had to fend off media controversy over her adoptive native heritage, and early rumors of trouble in her marriage to Lange. But although their careers often keep them apart, producer and star now appear to be living happily ever after. They call home a 1,200-hectare retreat with a private lake in upstate New York. And last week, Twain told Maclean's that they are seriously thinking of moving to Europe. They have begun looking for a house in the Swiss countryside.

Eileen Regina Twain - who rechristened herself Shania seven years ago - has certainly fulfilled the promise of her name, which means "I'm on my way" in Ojibwa. Now 32, she has sold more albums than any female country singer in history. Breaking a record that it took Patsy Cline 40 years to set, her 1995 CD The Woman in Me has attained sales of 12 million copies worldwide - two million of them in Canada alone. Twain's new album, Come on Over, which is nominated for three awards at this Sunday's Junos in Vancouver, has sold 4.2 million after just five months of release. And what is remarkable is that Twain has done it all without performing live. Instead, she has spent the past three years working as an indefatigable publicity machine - parading through talk shows, shopping malls and radio stations from Alberta to Australia.

Now, however, Twain is finally ready to hit the stage. She has put together a nine-piece band, and plans to launch a tour of Canadian hockey arenas on May 29 with a two-night stand in Sudbury, Ont., followed by a swing through Edmonton, Saskatoon, Calgary and Vancouver in early June. After some U.S. dates on the West Coast, she plans to play Toronto and Montreal in August, then smaller Canadian centres in the fall. Twain hopes to be on the road for most of this year and next. And anyone watching her rehearse and perform with her band last month at a Nashville TV studio could see that this is no typical country act. It is a hip, urban-looking outfit with an aggressive three-piece fiddle section and the energy of a pop band. "Basically, the show will be a party," says Twain, "and I'm the hostess. It's not going to be that slick. Just high energy, great lights and great sound."

With her music, Twain has goosed the tired country format with a well-aimed kick of sexy common sense. Her songs, which she co-writes with Lange, range from domestic-bliss ballads to sassy rockers that taunt and tease. In Don't Be Stupid (You Know I Love You), she offers feisty reassurance to a jealous mate. In That Don't Impress Me Much, she sings, "OK, so you're Brad Pitt ... so you've got the looks, but have you got the touch?" This is not hurtin' music, but painless pop. "Shania Twain has carved out her own place in country," says Chet Flippo, Nashville correspondent for Billboard. "Until she came along, there was no job description for what she is - a pop femme fatale in country, for want of a better term. She's playing by her own rules. And she's changing the audience."

Twain, meanwhile, is spearheading a country music invasion from Canada that is rejuvenating an industry rooted in the American South. "She's only the tip of the iceberg," says Nashville music journalist Robert K. Oermann. "A lot of the freshest sounds in country music are coming from Canada. The industry is looking north, because that's where the authenticity is."

Along with Céline Dion, Alanis Morissette and Sarah McLachlan, Twain also belongs to a brave new wave of Canadian women who have taken the U.S. music industry by storm. And judging by the current slate of Juno nominees, a new generation of talent, both male and female, is hot on their heels. If Dion is the pop diva, Morissette the angry young rocker and McLachlan the sensitive folkie, Twain is the no-nonsense sex symbol - a take-charge woman line-dancing down the middle of the road, splitting the difference between feminine compliance and feminist effrontery.

Twain's voice has a melting twang, enough to conjure up country, yet more suggestive of the boudoir than the barn. Her songs are flavored with fiddle and steel guitar, but Lange - who has put his studio stamp on Def Leppard, AC/DC and Bryan Adams - upholsters the music with lush arrangements typical of rock. "There are a lot of country fans who wouldn't usually be interested in as progressive a sound," says Twain. "And by the same token a lot of pop people like my music who wouldn't usually be attracted to country." With the new album, Twain's image, along with the music, creeps closer to pop. On the poster for it, denim and cowboy chaps have given way to faux-leopard and black leather. And in the video for Don't Be Stupid, she is in black sequins, river-dancing across a flooded alley.

While there is no denying her talent as a singer and songwriter, image is an integral part of Twain's appeal. She is a country singer who looks like a supermodel. Hollywood has, predictably, taken notice - the singer has turned down a stream of movie offers, including a role opposite Al Pacino. On camera, Twain projects a playful sexuality, an allure that is part come-on, part come-off-it. Like a PG version of Madonna, Twain promotes the flirtatious co-existence of glamor and self-empowerment. She is country's Cosmo-girl, a fantasy that works for both men and women. The video for her latest single, the ballad You're Still the One, unfolds like a Harlequin romance, with Twain on a moonlit beach in a silky robe, dreaming of a Calvin Klein hunk, who steps from the bath dripping wet and lets his towel fall to the floor as he slides into her bed.

No country singer has used video to promote herself with as much audacity as Twain. In fact, it was her very first video - a sexy, midriff-baring number from her first album - that hooked her most important fan. Lange saw it in 1993 and phoned her out of the blue. The same footage caught the eye of actor Sean Penn, who directed a video for her. John and Bo Derek (10) also took notice, and together they shot the first video from the second album, with Twain dancing on a diner countertop in a hot red dress.

Twain's style has drawn some flack from traditional quarters of country music. Guitarist Steve Earle once dismissed her as "the world's highest paid lap dancer." And some critics dwell on the fact that, since her breakthrough, she has never proven herself as a performer, except through a camera lens. Others suggest she is a studio Barbie created by a Svengali husband and a high-powered rock management (Twain is now handled out of Connecticut by Jon Laundau, who represents Bruce Springsteen). "A lot of people are accusing her of being packaged," concedes Luke Lewis, Nashville president of her Mercury label. "But I don't think this is a marketing-driven artist. It's been her vision from the beginning - all the clothes, all the looks, all the concepts."

In person, Twain certainly seems self-possessed. Sitting down for an interview in a Nashville hotel suite, she extends a firm handshake. In black pants, a black leather vest and a white T-shirt showing a sliver of midriff, she looks perennially ready for her close-up. She does not drink or smoke. She keeps her five-foot, four-inch, 110-lb. frame fit with regular workouts. Her skin has the glow of a woman who rides horses to relax. But Twain's clear-eyed charisma also works as a mask. She never lets down her guard, which can be frustrating for a photographer or interviewer hoping to catch her in a candid moment. Still, for a woman who is so poised and put together, it is a relief to know that she finds fault with her body. "I don't like my legs," she says flatly when asked why she sings about short skirts but never wears them.

It is late afternoon, and Twain has spent the day doing nonstop interviews with country radio broadcasters, ending each one with a snapshot and an autograph. Over and over, she answered questions about the new ripple in her hair, explaining that it comes from a curling iron, not a perm. One unctuous radio host had an unusual request.

"If you wouldn't mind calling me Sweet Cheeks, maybe once," he said.

As the tape rolled, he introduced his guest. "Here we are in Shania Twain's hotel room ..."

"And I'm with Sweet Cheeks," she said.

"See, Shania Twain does call me Sweet Cheeks ... I'll pay you later."

"Just leave it on the dresser."

No wonder she is eager to start touring. "I want to do less talking and more singing," says Twain. Her tour bus is under construction. "It's not going to be opulent," she insists. "There's not going to be any marble or anything. I want it to feel like home, with a fairly big kitchen space because I'm going to cook a lot." She plans to tour with her dog, a German shepherd named Tim, and one of her five horses, an Andalusian purebred named Dancer. Dancer will get his own trailer.

Twain, meanwhile, has handpicked a versatile touring band. The musicians all happen to be good-looking. They all sing, and most play more than one instrument - including 27-year-old Cory Churko, a Vancouver fiddler-guitarist who has spent more time playing rock than country. "She wanted a young, energetic, rocking band," says Churko, who quit his job as a computer animator to enlist. Twain is categorical about her criteria: "I can't have anyone in the band who doesn't have my energy. I don't want people who have been on the road for years and are just doing it in order to do it. And I like a clean band. I don't like drugs. I don't like alcohol. I like to have clean-living people around me."

Is she not nervous about performing live? "I'm going to be overwhelmed at first," Twain admits. "But it's going to be fun, not scary." Although she has not toured since she became a star, Twain points out that she has 20 years of stage experience under her belt - beginning at the age of 8, when her parents first started dragging her out of bed so that she could sing (legally) at the Mattagami Hotel bar in Timmins after it had stopped serving liquor. Talk about paying your dues.

"I love being in front of a live audience where I can control things," says Twain. "What I'm least comfortable with is the studio or anything contrived. I'm never at my best on television. There's a row of cameras between you and the audience, and it's very weird, very confusing."

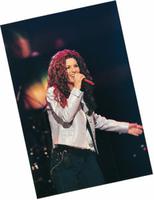

Shania Twain is onstage, rehearsing with her band for a taping of TNN's Prime Time Country. The TV studio occupies a wing of Nashville's Grand Ole Opry. As the nine-piece band runs through Don't Be Stupid, its young black drummer, wearing headphones in a Plexiglas booth, plays to a pre-recorded cue track. And although Twain is singing live, her vocals are perfectly synced to the song's video, which is projected behind her.

The band plays with unerring precision, fiddles cutting in and out with the galvanized attack of a horn section. Twain, meanwhile, delivers her songs with polished moves that barely change from one take to the next. The toss of the hair, the hand-slap on the hip, each gesture seems built into the song. And as cameras swoop around the stage, she seems in firm command, knowing exactly where to look and how to act. Twain lays to rest any doubts that she can deliver onstage. Her voice may lack power, but she sings with melodic ease. Even when she is just testing the microphone with some a cappella phrases, there is a seductive luxury to her unadorned vocals. And as she searches for an elusive intimacy, the one thing she fusses over is the sound - "too nasal ... too much bottom ... too much bite ... can you take a bit of the hard edge off? ..."

An hour after the rehearsal, the bleachers in the Nashville studio fill up with fans, who are taught how to produce polite "golf claps" or "thunderous applause" on cue. As the show begins, a life-sized poster of Twain in the form of a jigsaw puzzle is lowered from the lights. Counting down the days to her appearance, a piece has been added each week, and now that she has finally arrived, the last remaining segment - showing her belly button - is stuck into place.

Between songs, Twain puts in time on the talk-show couch. She tells a story about taking the train to the big city to appear on a TV show when she was 12. After a while, she realized she was going in the wrong direction. The conductor told her she could transfer at another station in six hours. "I said, 'You've got to stop the train right now because I'm going to be on TV.'' So they let me off in the middle of the bush with my guitar, like a little hobo. I caught a train going the other way in half an hour, but I did think, 'What if the train never comes?' "

Twain's childhood reminiscences often have an apocryphal ring, but perhaps they have just become buffed by constant repetition. This much is known. She was born in Windsor, Ont., on Aug. 28, 1965, the second of three daughters of an Irish-Canadian mother, Sharon, and her husband, Clarence Edwards, who is of Irish and French descent. By the time Twain was 2, her parents' marriage collapsed, and Sharon moved with the children to Timmins, where - four years later - she married Jerry Twain, an Ojibwa forester and prospector. He adopted the children, who automatically gained First Nations status.

Throughout her childhood, Twain was aware of her biological father, and he occasionally visited her family. But she kept his existence a secret until 1996, when The Daily Press in Timmins broke the story about the facts of her birth. There was a storm of controversy as Twain was accused of lying, and of enhancing her native heritage for the sake of her career. "It was very hard on my native family," she says. "I'm a registered band member. I've been part of their community since I was a little child. It's very hurtful to know there are people who want to unravel all that."

When asked why she didn't tell the truth from the beginning, Twain's consistently perky composure gives way to a burst of anger. "Half the people in my life didn't know I was adopted," she says. "Why should I have told the press? It frustrates me no end, I can't tell you. I have never referred to Jerry as my stepfather. I never even referred to Clarence as my father, and I didn't care if I was ever in contact with that family again." Then, she adds: "It's never been an issue for me, but it's an issue for everyone else all of a sudden. It's like a big black hole."

In his recent book about country music, Three Chords and The Truth, U.S. author Laurence Leamer went so far as to call Twain's life story "a brilliant reconstruction," claiming that she has exaggerated the poverty of her childhood. Twain says that in fact the reverse is true: "Let's put it this way. I'm not sugarcoating, but I've revealed very little of the true hardship and intensity of my life, and that's the way I'm going to keep it."

As a child, the singer recalls, she sometimes went for days with nothing to eat but bread, milk and sugar heated up in a pot. "I hardly ever took a lunch to school. I'd say I'm not hungry. Or I'd bring, like, mustard sandwiches." But Twain has fond memories of learning to hunt and trap in the bush with her father - although she is now vegetarian. And alone in nature, she would create her own world. "I'd take my guitar for a walk and go to a field or the river and write songs," she says. "As a kid I had three dreams: to live in a brick house and eat roast beef, to be kidnapped by Frank Sinatra, and to be Stevie Wonder's backup singer. It was never my dream to be a star. That was my parents' dream. I guess they prayed real hard."

Twain was a reluctant performer, but her parents were persistent. By her early teens, she was popping up on programs such as The Tommy Hunter Show. But only when she discovered rock 'n' roll did she begin to enjoy the stage. "I couldn't hide behind my guitar," she says. "I sensed a freedom that I'd never sensed before." Twain completed high school while working at McDonald's and playing bars. Meanwhile, her parents started a reforestation business, and from age 16 she spent summers in the bush, learning about chainsaws and seedlings, until she was supervising her own native crew.

In 1987, the death of her parents changed everything. Twain, then 22, was suddenly forced to become a mother to her younger sister and two teenage brothers. Her manager at the time, Mary Bailey, came to the rescue with a steady gig at the Deerhurst Resort in Huntsville - as a lounge act and as a singer in glitzy cabaret revues such as Viva Vegas. Twain paid her dues for three years at Deerhurst. And Bailey lured a Nashville producer up there to see her perform - which led to her first record deal in 1991.

The first album, Shania Twain, had modest sales of about 100,000 copies. But it led to the romance with Lange, which started as a songwriting relationship over the phone. They finally met face-to-face in Nashville, and married at the Deerhurst six months later. Lange, meanwhile, helped finance The Woman in Me, a $700,000 work of studio wizardry touted as the most expensive country album ever recorded.

Since then, reports of ruin have swirled around Twain's marriage. "People in the industry were calling my management all the time asking, 'Are they really divorcing?' " she recalls. "Most people thought we were unlikely to succeed. My family were like, 'You just met this guy, you can't get married.' " Twain adds that You're Still the One is about Mutt - and "the nice feeling that we've made it against all odds."

They do seem an odd couple. She spends much of her life in a professional romance with the camera; he is so obsessively media-shy that it is impossible to find a published Mutt Lange picture or interview. The South African-born producer never shows up with his wife at industry functions where he might be photographed. At the TNN show in Nashville, however, a backstage sighting - of a blue-denimed figure in his 40s, tall and handsome with a shag of blond hair - confirmed that he does, in fact, exist.

How can such a reclusive husband get along with such a public wife? "I make my living partly by being a celebrity," says Twain. "But I would love to have his life, to do the music and not have to be famous. I'm more private than people realize. I'm not that easy to get to know. My husband's the only one who really knows me. To get through the kind of life I've been through, you have to be strong, and it's wonderful when you find the right person who can share everything about you."

Whatever pain lies behind Twain's nearly seamless public persona, there is little evidence of it in her music. "It's not pure emotion. I mould it so it can be applied to people's lives. But I write a lot of music I don't share, for the same reason people have diaries. I just express myself. It's not a creative thing. It's therapeutic."

Twain's celebrity has brought its own pain to her family, and not just the native heritage controversy. Over the years, her younger brothers, Mark and Darryl, now 25 and 24, have been in and out of trouble with the law. In 1996, after they were caught trying to steal cars from a Toyota dealership in Huntsville, everyone from the CBC to The National Enquirer chased the story. "It's difficult for them to be exposed if they do anything wrong," says their sister, "but at the same time it helps keep them straight." Her brothers, she adds, are now working in the bush cutting timber.

Back in the Grand Ole Opry studio in Nashville, the host of TNN's Prime Time Country regales his audience with tales of Twain's days as a forestry worker in an exotic place called Timmins. Getting her to put on a yellow hard hat, he challenges the singer to a log-cutting contest. Picking up one of two small electric chainsaws, she says: "This is kind of dinky. It's what men would call a woman's chainsaw." They start their engines. And as the crowd roars, Twain cuts through her log in seconds, leaving her host in the sawdust - and her legend intact.

Maclean's March 23, 1998

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom