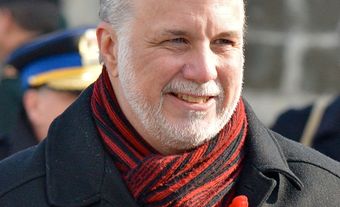

François Legault, businessman, politician and premier of Quebec (born 26 May 1957 in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Québec). Co-founder of Air Transat, François Legault was a minister in the Parti Québécois governments of Lucien Bouchard and Bernard Landry. As leader of the Coalition avenir Québec, a political party he founded in 2011, he was elected premier of Quebec on 1 October 2018. Some of his accomplishments are the adoption of Bill 21 (An Act Respecting the Laicity of the State), Bill 96, which made several amendments to the Charter of the French language, and the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Education and Early Career

François Legault earned his BA in business administration (public accounting option) at the École des Hautes Études commerciales (HEC), the business school at the Université de Montréal, in 1978. Legault then became an auditor at Ernst & Young, a position he held until 1984. That same year, he completed his master’s degree in business administration (finance option), also at HEC.

In 1985, Legault became the director of finance and administration at Nationair Canada and then marketing director at Québécair. In 1986, with Jean-Marc Eustache and Philippe Sureau, Legault created Air Transat and was its president and chief executive officer until 1997. Air Transat quickly became one of the largest airline companies in Canada offering charter flights (see Air Transport Industry). From 1995 to 1998, Legault sat on the boards of various companies, including Provigo Inc., Culinar, Sico, Technilab Inc., and Bestar Inc., as well as the Marc-Aurèle Fortin private museum.

Member of the National Assembly and Parti Québécois Minister

In 1998, Legault made the jump to provincial politics. On 23 September 1998, before Legault was elected to the National Assembly, Premier Lucien Bouchard appointed him Minister of Industry, Commerce, Science and Technology. In the 30 November 1998 general election, Legault ran for the Parti Québécois (PQ) in the riding of Rousseau and won.

Two weeks after his election, Legault became Minister of State for Education and Youth and vice-president of the Treasury Board. In January 2002, Bernard Landry, who had taken over from Lucien Bouchard as leader of the PQ and premier, appointed Legault Minister of Health and Social Services, a position Legault held until the April 2003 general election.

Following the victory of Jean Charest’s Liberals, Legault became the Official Opposition’s spokesperson on the economy and finance — a role he played from 2003 to 2007. The surprisingly strong showing of the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) in the March 2007 general election relegated the PQ to the second opposition group. Legault continued to act as spokesperson on finance and economic development matters for two years, but he resigned his position as member of the National Assembly on 25 June 2009 because he found working in opposition very frustrating.

Founding of the Coalition Avenir Québec

Legault did not leave public life behind altogether. In 2010–11, he made a number of public appearances and sounded out public opinion. On 21 February 2011, along with entrepreneur Charles Sirois, he established the Coalition pour l’avenir du Québec (Coalition for the Future of Québec), a non-profit organization. After releasing four position papers describing his priorities for revitalizing Québec, Legault toured the province in the fall of 2011.

On 4 November 2011, the Coalition became a registered political party in Québec. The party took the name Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ). Legault’s party merged with the Action démocratique du Québec, the former party led by Mario Dumont, on 14 February 2012. In the meantime, four independent members of the National Assembly decided to join the CAQ. In early January 2012, François Rebello, a member of the PQ, also quit his caucus to join the CAQ.

Coalition Avenir Québec Platform

As soon as he returned to the political arena, Legault capitalized on the accusations of corruption that were swirling around Jean Charest’s Quebec Liberal Party. Using the slogan “Québec can and must do better,” the party unveiled its priorities: enhancements to education; quality, accessible healthcare; a plan for making Québécois the masters of their economic development; promotion of the French language and of Québec’s culture; and integrity in public life.

Claiming to be neither right- nor left-wing, the new party proposed to put aside the constitutional debate that was paralyzing the province and to act in the best interests of Québec. In the preface to the Revival Plan for Québec, which contained the CAQ’s 2012 platform, Legault stated very clearly that “the Coalition will promote neither sovereignty nor Canadian unity.” Therefore, despite his 2005 study Finances d’un Québec souverain (Finances of a Sovereign Québec), in which he demonstrated the economic feasibility of an independent Québec, by 2012 Legault had clearly broken with his sovereigntist convictions.

During the spring 2012 Québec student strike, the CAQ supported the tuition fee increase put forward by the Liberal Party. However, the CAQ proposed to implement it more gradually in order to ensure adequate financing for universities and “neutralize the effects of the increase on lower-income and middle-class students” (see Educational Opportunity). Legault seized the opportunity provided by the conflict to promote his party’s position that Québec needed to reassert the value of education — to view it as a source of wealth. To reduce the student dropout rate, the CAQ suggested a different concept of the school day schedule; in particular, the CAQ proposed adding five hours a week to the secondary school timetable. The party’s platform also proposed abolishing school boards to give more autonomy and initiative to individual schools, enhancing the value of the teaching profession through measures such as pay raises for teachers, and improving financial aid to students.

General Election of 4 September 2012

Unable to reach an agreement with the students and counting on the support of the public in the tuition debate, Jean Charest called a general election. A summer election campaign gave Legault the opportunity to engage in debate on matters of substance.

Proclaiming itself to be staunchly nationalist, the CAQ took as its mission the creation of a strong and confident Québec with the strength and resources to fulfil its ambitions. Calling for a stronger policy on the use of the French language and the dissemination of Québec culture, healthcare and education reforms, as well as action to battle corruption, Legault led a vigorous political campaign during the summer of 2012. Counting on anglophone and allophone voters who might be ready to turn away from the Quebec Liberal Party because of rumours of illegal political financing and collusion with the construction industry, Legault highlighted his extensive and unblemished experience in politics and as a cabinet minister. Positioning the CAQ between Jean Charest’s and Pauline Marois’ parties, Legault ran a slate of 125 candidates.

However, despite positive polls throughout the campaign, the results of the 4 September 2012 election were disappointing for the Coalition avenir Québec. The party elected only 19 members to Québec’s National Assembly, even though François Legault’s team collected 27 per cent of the votes. The CAQ was only a few points behind the Quebec Liberal Party, which received 31.2 per cent of the votes and was called upon to form the Official Opposition to the elected PQ government.

General Election of 7 April 2014

After one year of work as party leader, Legault published a book entitled Cap sur un Québec gagnant : Le Projet Saint-Laurent (Setting Course for a Successful Québec: The St. Lawrence Project) in the fall of 2013. In this book, the leader of the CAQ invited the people of Québec to create a focal point of innovation, high-quality education and entrepreneurship in the St. Lawrence Valley by emulating the model of Silicon Valley, California. Legault also proposed making the St. Lawrence River and the St. Lawrence Seaway the cornerstone of economic development in Québec. The cleanup of shorelines and riverbanks, the impetus given to universities by research funding, tourism, and oil resource development would ensure that the people of Québec enjoyed the quality of life they expected.

The book served as the CAQ’s election platform during the spring 2014 election campaign. Even though the CAQ received fewer votes (23 per cent) than in the previous election and lost four ridings in the Québec City region, the party elected 22 members to the National Assembly — three more than in 2012 — and succeeded in establishing a foothold in the Montréal suburbs at the expense of the PQ. The Quebec Liberal Party, led by Philippe Couillard, formed the new government, and the PQ was relegated to Official Opposition.

General Election of 1 October 2018

On 23 August 2018, Premier Philippe Couillard called an election for 1 October 2018. This was the first fixed-date election to occur in the province of Quebec.

The Coalition avenir Québec campaigned under a simple, one-word slogan: Maintenant. With respect to education, the electoral platform called for lower school taxes and universal free pre-kindergarten for children four years of age. In the area of health care, Legault’s team promised improved access to front-line care and reasonable wait times to see family physicians. Certain proposals proved controversial, such as reducing immigration levels to 40 000, a decrease of 23.5 per cent from 2017 (see Québec Immigration Policy) and requiring new arrivals to pass a test evaluating their knowledge of Québec values as well as a French-language test after four years.

The 1 October election results allowed the CAQ to form a majority government. This victory put an end to the exchange of power between the Quebec Liberal Party and Parti Québécois that began in 1970 when the Liberal Party of Robert Bourassa won the election. With 74 out of 125 seats in the National Assembly and 37.42 per cent of the vote (resulting in a gain of 52 seats), Legault’s party emerged well ahead of its main competitors. The Liberals managed to elect only 31 members to the National Assembly (39 fewer than in the 2014 election), while the PQ won only 10 seats (down from 28 in the previous election). Québec solidaire was the only other party to gain a share of seats, jumping from 3 to 10 members. Women were elected to the National Assembly in unprecedented numbers, with 53 seats in total (28 belonging to the CAQ) representing 42.4 per cent of sitting members.

Elected in the riding of L’Assomption, François Legault became the 32nd premier in Quebec’s history.

First Mandate (2018–2022)

The CAQ’s first government was marked by the controversial adoption of important legislation addressing nationalist and identity issues. Bill 21 (An Act Respecting the Laicity of the State) banned certain government employees in positions of authority from wearing religious symbols. (See also Québec Values Charter.) The government also adopted a major reform of the Charter of the French Language, introducing new regulations for the anglophone cégeps and imposing the use of French language as the exclusive language of government and as the language of work in businesses with more than 25 employees. (See Quebec Language Policy.) These policies were opposed by anglophone groups and religious minorities. Both bills also raised controversy because of their use of the notwithstanding clause, which allows the government to override certain provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The CAQ’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic was controversial. Compared to the rest of Canada, Quebec suffered the highest number of deaths linked to COVID-19. For some critics, Legault’s government reacted to the pandemic through particularly heavy-handed measures. It implemented multiple lockdowns and a vaccine passport for patrons accessing certain events and restaurants. Perhaps most controversially, the government introduced two curfews during the pandemic. Other critics felt that the government was not doing enough, notably by reopening schools at certain points of the pandemic. The management of long-term care centres, or CHSLDs, early on in the pandemic was also heavily criticized.

Second Mandate (2022–)

The CAQ entered the election campaign way ahead of its rivals in the polls. The debates focused on the immigration and French language, the health care system and inflation. François Legault’s CAQ was the undisputable winner of the October 2022 elections, despite some critical voices who deemed the party’s election campaign rather weak. The CAQ won almost 41 per cent of the vote and elected 90 members of the National Assembly out of 125. Compared to the CAQ, the Quebec Liberal Party elected only 21 members with less than 14.4 per cent of the vote while the Parti Québécois barely elected 3 members with 14.6 per cent of the vote. Québec solidaire managed to get 11 members elected, obtaining 15.5 per cent of the vote. The Conservative Party of Quebec received 12.9 per cent of the vote but did not get any seat in the National Assembly.

Awards and Honours

Legault has been a Fellow of the Ordre des comptables agréés du Québec (Order of Chartered Accountants of Québec) since 2000.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom