Origin and Definition

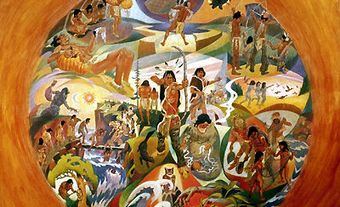

The potlatch (from the Chinook word Patshatl) is a ceremony integral to the governing structure, culture and spiritual traditions of various First Nations living on the Northwest Coast (such as the Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth and Coast Salish) and the Dene living in parts of the interior western subarctic. While the practice and formality of the ceremony differed among First Nations, it was commonly held on the occasion of important social events, such as marriages, births and funerals. A great potlatch might last for several days and would involve feasting, spirit dances, singing and theatrical demonstrations.

Purpose

Historically, the potlatch functioned to redistribute wealth in what some refer to as a gift-giving ceremony. Valuable goods, such as firearms, blankets, clothing, carved cedar boxes, canoes, food and prestige items, such as slaves and coppers, were accumulated by high-ranking individuals over time, sometimes years. These goods were later bestowed on invited guests as gifts by the host or even destroyed with great ceremony as a show of superior generosity, status and prestige over rivals.

In addition to its economic redistributive and kinship functions, the potlatch maintained community solidarity and hierarchical relations within and between bands and nations. A highly regulated ceremony, the potlatch conferred status and rank upon individuals, kin groups and clans, and established claims to names, powers and rights to hunting and fishing territories.

History

As part of a policy of assimilation, the federal government banned the potlatch from 1884 to 1951 in an amendment to the Indian Act. The government and its supporters saw the ceremony as anti-Christian, reckless and wasteful of personal property. They failed to understand the potlatch’s symbolic importance as well as its communal economic exchange value.

The last major potlatch, that of Daniel Cranmer (Kwakwaka’wakw) from Alert Bay, British Columbia, was held in 1921. The goods were confiscated by agents of the Indian Department and charges were laid.

By the time the ban was repealed in 1951, due largely to the difficulties of enforcement and changes in attitudes, traditional Indigenous identities had been damaged and social relations disrupted. However, the ban did not completely eradicate the potlatch, which still exists in various communities today.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom