Racial segregation is the separation of people, or groups of people, based on race in everyday life. Throughout Canada’s history, there have been many examples of Black people being segregated, excluded from, or denied equal access to opportunities and services such as education, employment, housing, transportation, immigration, health care and commercial establishments. The racial segregation of Black people in Canada was historically enforced through laws, court decisions and social norms.

See also Anti-Black Racism in Canada.

Chattel slavery, the practice of treating people as personal property that can be bought, sold, traded and inherited, was abolished in most British colonies, including Canada, in 1834. (See Slavery Abolition Act, 1833). However, the segregation of Black people in Canada was justified for many years afterwards by perpetuating ideas about racial inferiority that had been used to justify Black enslavement. Historically, practices of racial segregation differed across the country, often according to province or local community.

DID YOU KNOW?

The town of Saint John, New Brunswick was incorporated by royal charter in 1785. The first mayor was Gabriel G. Ludlow, a slave owner. While Ludlow served as mayor from 1785 until 1795, several restrictions were placed specifically on the growing Black community. Many of these restrictions stayed in place long after he left office. For example, until 1870, Black people could not take an oath to gain the status of free men. They were prohibited from practicing a trade or selling goods in the city, barred from fishing at Saint John Harbour, and could not live within the city limits unless they were employed as a servant or labourer.

Education

Many Black Canadians were racially segregated in primary schools by the mid-19th century. Ontario and Nova Scotia set up legally segregated schools to keep Black students separate from white students. Black students had to attend different schools or attend at different times. In some other provinces, white families enforced an informal segregation by blocking Black students from attending school. Activists from the Black community fought against segregation in schools. (See Leonard Braithwaite.) The last segregated school in Ontario closed its doors in 1965; the last one in Nova Scotia closed in 1983.

Canadian universities, particularly medical schools, often rejected Black students’ applications on the basis of race. This was notably the case of Dalhousie University, the University of Toronto, McGill University and Queen’s University. Admitted Black students faced restrictions that white students did not have. Only a few hospitals accepted Black medical interns. Black women who applied to study nursing also faced racial restrictions.

See Racial Segregation of Black Students in Canadian Schools.

Housing and Home Ownership

Historically, Black Canadians access to colonial land grants and residential housing was often restricted based on race. For instance, some Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia and Ontario did not receive land grants as promised. Those who did were given smaller allotments located on land that was of poorer quality, and in places physically segregated from white settlers, such as the historically Black communities of North Preston in Nova Scotia and Elm Hill in New Brunswick.

There are many examples of land titles with restrictive covenant clauses used to prevent the sale or rental of property to people of African descent and other racialized groups. For example, a clause in Vancouver real estate deeds going back to at least 1928 and included as late as 1965 stated, "That the Grantee or his heirs, administrators, executor, successors or assigns will not sell to, agree to sell to, rent to, lease to, or permit or allow to occupy, the said lands and premises, or any part thereof, any person of the Chinese, Japanese or other Asiatic race or to any Indian or Negro." In the 1920s, city officials in Calgary, Alberta also codified restrictive covenants to prevent Black residents from purchasing homes outside of the boundaries of the railway yards. In Sarnia, Ontario, a 1946 property deed for a Lake Huron community of approximately 100 cottage lots specified that property could only be owned by whites of a particular background and could not be “transferred by sale, inheritance, gift, or otherwise, nor rented, licensed to or occupied by any person wholly or partly of negro, Asiatic, coloured, or Semetic [sic] blood...” (See Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians; Anti-Semitism in Canada.)

There are also examples of Blacks being routinely turned away when seeking rental accommodations based on their race. This meant they often had limited options in terms of where they could live. Over time, this systemic discrimination has resulted in the heavy concentration of Black residents in some neighbourhoods in major urban centres in Canada such as Little Burgundy in Montreal.

Employment and Trade Unions

Racial segregation practices have also extended to many areas of employment in Canada. Black men and women were historically relegated to the service sector – barbers, waiters, janitors, sleeping car porters, general labourers, domestic servants, waitresses, laundresses – regardless of their educational attainment. White business owners and even provincial and federal government agencies did not traditionally hire or promote Black people.

When the labour movement took hold in Canada near the end of the 19th century, workers began organizing and forming trade unions with the aim of improving the working conditions and quality of life for employees. However, Black workers were systematically denied membership to these unions, and worker’s protection was reserved exclusively for whites.

Military Service

Black men have served in militias, the British Army, and in the Canadian military, even when at times they were forced serve in racially segregated units. In 1859, when Black men in Victoria, British Columbia expressed their interest in signing up as volunteer fire fighters ( see Fire Disasters in Canada), they were rejected by the white male organizing committee. Governor James Douglas approved the establishment of a militia for Black men wishing to offer their service to help defend against American expansion threats. The unit, officially sworn in in 1861, was called the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Company, also known as the African Rifles.

Black men who attempted to enlist at the outbreak of the First World War were routinely turned away and told it was a “White Man’s War.” Seeking more men to serve in the war effort, and in response to the pressure of Black communities across Canada, an all-Black unit was proposed and approved in July 1916. While some individual Black men were accepted in some combat units, the majority of Black men, more than 600, who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force, had to enlist in the No.2 Construction Battalion that was stationed in Pictou, Nova Scotia, no matter where they lived in Canada. The racially segregated unit did not see combat as white soldiers refused to fight along side Black men.

Commercial Establishments

Theatres

There was segregated seating in some performance and movie theatres. In 1860, the dress circle of British Columbia’s Victoria Colonial Theatre was reserved for whites. Black seating was limited to the gallery by the theatre owner. An altercation took place when Mifflin Gibbs, his wife Maria, friend Nathan Pointer and his young daughter attempted to sit in section reserved for whites while attending a charity event.

In February 1914, Charles Daniels, a porter, purchased a reserved seat on the ground floor of the Sherman Grand Theatre in Calgary, Alberta for a performance of King Lear. When he went to watch the show, he was refused entry to the main floor due to the colour of his skin. The box office clerk offered him seats in the upper balcony instead, where Black people were permitted to sit. Daniels rejected this and hired a lawyer to file a lawsuit. The judge ruled in Daniels’ favour, awarding him $1,000.

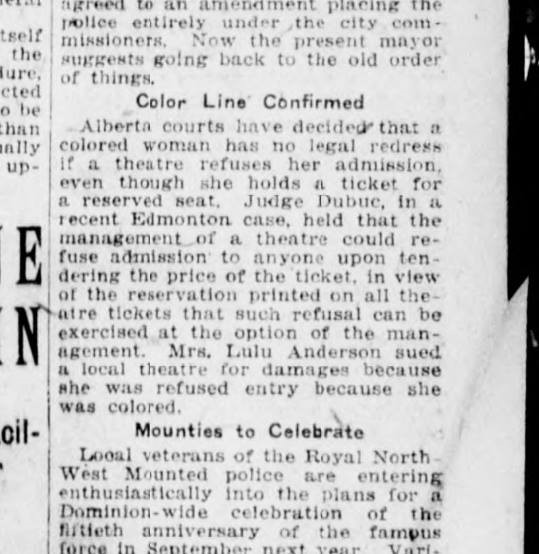

Some theatres in Saint John, New Brunswick closed their doors to Black visitors in 1915. Twenty-two years before the Viola Desmond incident in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, another Black woman named Lulu Anderson was denied admission to the Metropolitan Theatre in Edmonton, Alberta. In November 1922, Anderson sued the theatre for refusing to sell her a ticket to watch a movie, but the provincial courts ruled in favour of the theatre owners.

In Windsor, Ontario, the Palace Theatre maintained a “Crow’s nest” for Black customers, in reference to Jim Crow segregation laws and practices. In Montreal, the Loew’s Windsor Theatre publicly announced that Black customers would have segregated seating in what they called a “Monkey cage,” the upper balcony of the opera house.

Barbershops

White barbers were known to refuse to cut Black men’s hair. Former Senator Calvin Ruck, for example, was refused service in a Shearwater, Nova Scotia barbershop. In Dresden, Ontario, all five barbershops and the sole hair salon would not serve Black men and women.

Restaurants and Inns

It was common for restaurants across Canada to deny service to Black people. In 1943, civil rights activist Hugh Burnett, aged 25, was refused service in a restaurant in Dresden, Ontario while wearing his military uniform. When Burnett wrote a letter of complaint to then Liberal federal deputy minister Louis St. Laurent, he was told that racial discrimination was not against the law in Canada. In 1947, Dennis St. Helene, a West Indian student studying and working in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia could not purchase a meal at a local restaurant, because “[W]hite customers would not come in.”

While bars, pubs and taverns were public spaces of inter-racial interaction they were also another venue of public accommodations that were known to turn away potential Black patrons. On 11 July 1936, Fred Christie and another Black acquaintance Emile King, were refused service at the York Tavern in the Forum in Montreal after watching a boxing match. Christie sued for $200 and won in provincial court. Christie was awarded $25 and the tavern was ordered to pay his court costs. However, the tavern owners successfully appealed. Determined, Christie took his case all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1939. They dismissed his case, arguing that private businesses were able to discriminate based on the race of their choosing. Some taverns in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and British Columbia allowed Black visitors, but had designated tables or side rooms for Black patrons.

Hotels and inns in large cities and small towns frequently denied accommodation to Black people. During the mid to late 19th century, there were only a handful of Black-owned inns where Blacks could stay.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Prince Edward Hotel in Windsor, Ontario denied African American civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune a room in 1954 when she and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt were invited speakers at Emancipation Day in the city. Roosevelt was offered a room, but in the end they both opted to lodge in Detroit, Michigan for the night instead.

Between 1949 and 1967, there were Canadian entries in the American-published Green Book, the travelling guide for Black motorists that identified places that welcomed Black patrons. This speaks to the racial climate of the time.

Recreational Facilities

Black Canadians could not historically access many public recreational facilities. In 1923, the Edmonton city council passed an ordinance that barred Blacks from swimming in city pools after an outcry from the white public and the Edmonton Exhibition Association which opposed mixed bathing. Skating rinks (see Ice Skating) also refused admission to Black people, no matter the age. In 1945, 15-year-old Harry Gairey Jr. and his white friend Donny Jubas went skating at an indoor ice rink in Toronto, but they were told that Harry could not get a ticket, because they did not sell tickets to Black people.

On a Civic Holiday weekend in August 1930, approximately 300 members of the three Black churches in Chatham, Ontario who were visiting Seacliff Park in Leamington, Ontario were ordered by the mayor and two city councillors to leave the park because they had breached a common local convention “which prevents colored people from making a rendezvous of the town or township or holidaying at the Park, especially on a public holiday.”

Cemeteries

Black people experienced racial segregation even in death with segregated cemeteries. The Camp Hill Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia had a “coloured section” where veterans of the No.2 Construction Battalion were buried. It was the policy of the St. Croix Cemetery near Windsor, Nova Scotia that “Not any negro or coloured person shall be buried in the St. Croix Cemetery.” Cemeteries in Fredericton, New Brunswick and Colchester, Ontario also restricted burials based on race.

Transportation

Racial restrictions in public accommodations extended to some forms of public transportation such as steamboats and stagecoaches. In the 1850s, Blacks were barred from purchasing cabin-class tickets on a steamer in Chatham, Ontario. In his 1841 tour of southwestern Ontario, Toronto resident Peter Gallego, the son of a free Black man from Richmond, Virginia who settled in Toronto in the 1830s, was told that he was not allowed to sit in the carriage with the other passengers on a trip from Hamilton to Brantford because of his race. The driver would only transport him if he rode on the outside seat, but Gallego refused.

Immigration

The turn of the 20th century whites-only immigration policies, practices and restrictions were intended to keep Black and other non-white people out. The federal government mandated racial discrimination with the aim of keeping Canada British and anglophone. Section 38 of the 1910 Immigration Act permitted the government to prohibit the entry of immigrants "belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada, or of immigrants of any specified class, occupation or character." (See Racism.) These increased discretionary powers were in response to the vigorous campaigning of white men and women to ban any further Black immigration. Those campaigning included the Edmonton Board of Trade, the Orange Lodge, and the Edmonton chapter of the Order of the Daughters of the Empire, which petitioned Immigration Minister Frank Oliver concerning “the influx of Negroes” from Oklahoma. In 1911, the federal Liberal government under Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier drafted an Order-in-Council, a legal order to be declared by the governor general, that would ban Black Americans from coming in for one year. (See Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324 – the Proposed Ban on Black Immigration to Canada.) While the Order was not officially declared, the combined efforts effectively halted Black immigration into the Prairies by 1912 (see History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies). Some politicians instigated and endorsed anti-Black discrimination. In 1911, William Thoburn, the Conservative member for the Ontario riding of Lanark North, said in the House of Commons, "Let us preserve for the sons of Canada the lands they propose to give to n—rs."

Challenging Racial Segregation of Black Canadians

Black Canadians have a history of challenging racist laws and discriminatory practices. Many have fought over the years for desegregation and an increase in rights and freedoms in public spaces. Members of Black communities across the country held meetings and demonstrations, circulated petitions, lobbied politicians, refused to send their children to segregated schools, brought their children to white schools to force admission, sent delegations to government leaders, conducted direct action, civil rights testing and sit-ins, and published articles and letters to the editors in Black and mainstream newspapers. They filed lawsuits and appeals and organized funding support for people who took their cause to the courts. Black men and women formed organizations to collectively campaign for change and equal access in education, housing, and employment.

DID YOU KNOW?

There are many examples of community-based organizations established by Black Canadians to resist racism and fight for racial equality and social change. They include: The National Unity Association in Dresden, Ontario, the Black United Front in Nova Scotia, branches of the Associations for the Advancement of Coloured People, the Coloured Political and Protective Association of Montreal, the South Essex Citizen’s Advancement Association in Ontario, branches of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) across Canada, the Black Youth Organization

Many individuals are recognized for challenging anti-Black racism. Bromley Armstrong's long record of activism included testing the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1954, Ontario’s new legislation against discrimination. Armstrong and fellow activists of diverse backgrounds visited restaurants in Dresden, Ontario that continued to refuse service to non-white customers and applied to landlords in Toronto who turned away Black and other racialized renters. In Edmonton, Ted King challenged racial segregation in his role as the president of the AAACP. In 1959, he spearheaded a lawsuit against the Barclay Motel because the owner informed him that “we don’t allow coloured people here.” King used the courts to effect social change. Marlene Green founded the Black Education Project in Toronto in the late 1960s to advocate for Black students who experienced systemic racism in the public-school system. She wrote the first report on race relations in the Toronto Board of Education in 1979 after facilitating community consultations, which detailed recommendations to address parent concerns.

The human rights movement of the mid-20th century was spurred by countless Black people, other targeted groups, and their allies who resisted and struggled for change, equality, and justice. Black protest influenced the introduction of anti-racism legislation in different provinces and cities beginning in the 1940s, which decades later were reconsolidated into provincial human rights codes and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In 1944, Ontario enacted the Racial Discrimination Act, which prohibited the publication or display, of any notice, sign, symbol, emblem or other representation on lands, premises, by newspaper or radio, that indicated racial discrimination. Three years later, the city of Toronto passed an anti-discrimination law that prohibited places that required city licences to operate from practicing racial and religious discrimination, or their licenses would be revoked. Also in 1947, Saskatchewan became the first province to enact a Bill of Rights. (See Saskatchewan Bill of Rights.) In 1951, Ontario passed the Fair Employment Practices Act to target discrimination in hiring practices and workplaces by establishing fines as well as a procedure for complaints.

At the federal level, the Canada Fair Employment Practices Act became law in 1953. The two previous anti-discrimination laws introduced in Ontario led to the 1954 Fair Accommodation Practice Act of Ontario, which prohibited the denial of services or facilities to anyone that were intended to serve the public. The Canadian parliament passed a Bill of Rights in 1960, the first federal law to protect human rights and freedoms. However, it was only an ordinary statute and not enshrined in the Canadian Constitution, or the British North America Act. In 1982, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, entrenched in the new Constitution Act, provided a more comprehensive human rights legislation came into effect across Canada.

Conclusion

Racial segregation laws and common social practices have historically limited the freedoms of Black British subjects and, later, Black Canadian citizens. They imposed second-class citizenship on Black Canadians, while simultaneously giving white Canadians access to aspects of citizenship reserved only for them.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom