Refus Global Manifesto

We are the offspring of modest French-Canadian families, working class or lower middle class, who, ever since their arrival from the Old Country, have always remained French and Catholic through resistance to the conqueror, through strong attachment to the past, by choice and sentimental pride and out of sheer necessity.

We are the settlers who, in 1760, were first thrust into the fortress of fear, the usual refuge of the vanquished, and there abandoned. Our leaders took to the sea or sold themselves to the highest bidder, a practice they have continued to follow at every opportunity.

We are a small people huddling under the shelter of the clergy, who are the only remaining repository of faith, knowledge, truth, and national wealth; we were excluded from the universal progress of thought with all its pitfalls and perils, and raised, when it became impossible to keep us in complete ignorance, on well-meaning but uncontrolled and grossly distorted accounts of the great historical facts.

We are a small people, the product of a Jansenist colony, isolated, defeated, left a powerless prey to all those invading congregations from France and Navarre that were eager to perpetuate in this holy realm of fear (in-fear-is-the-beginning-of-wisdom!) the blessings and prestige of a Catholic religion that was being scorned in Europe. Heirs of papal authority, mechanical, brooking no opposition, past masters of obscurantist methods, our educational institutions had, from that time on, absolute control over a world of warped memories, stagnant minds and misguided intentions.

In spite of all this, our small people grew and multiplied in number, if not in spirit, here in the north of this huge American continent; we had strong, young bodies and hearts of gold, but our minds remained primitive, obsessed by the memory of Europe's past glories, disdainful of the true achievements of our own oppressed classes.

It seemed as if our future were set in stone.

Then wars and revolutions in the outside world broke the spell, shattered the mental block.

Irreparable cracks began to appear in the fortress walls.

Political rivalries became bitterly partisan, and, against all hope, the clergy became careless.

Then came rebellions, followed by a few executions, and the first bitter rifts opened up between the clergy and some of the faithful.

Slowly the breach widened, then narrowed, then once again grew wider.

Foreign travel became more common, with Paris as the main attraction. Too distant in time and space, too lively for our timid souls, a trip to Paris was often just an excuse to spend a holiday acquiring some long-overdue sexual experience and enough of the polish provided by a stay in France to intimidate the masses back home. With very few exceptions, our physicians, for example, whether or not they had actually made the trip, began behaving scandalously (we-have-a-right-to-make-up-for-those-long-years-of-study!).

Revolutionary publications, whenever we happened to stumble across them, were considered the virulent outpourings of a group of eccentrics. With our usual lack of discernment, we tended to regard academic activities in the same light.

In many cases, these trips also served as an unexpected wake-up call. Minds were growing restless, and more people began reading forbidden books, which brought some small hope and comfort.

Our minds were energized by the poètes maudits, who, far from being monsters of evil, dared to give loud and clear expression to feelings that the most wretched among us had always shamefully repressed for fear of being swallowed alive. The example of these men, who were the first to come to grips with everyday concerns about pain and loss, showed us the way. Their answers were so much more challenging, precise, and fresh than the age-old bromides being fed to us in Québec and in seminaries around the world.

We began to have higher expectations.

The collapse of the worn and tattered boundaries on our horizons made our heads spin. The shame of slavery without hope gave way to new pride in the knowledge that we could fight for our freedom.

To Hell with the aspergillum and the toque! They have extorted from us a thousand times more than they ever gave.

We passed beyond Christianity to touch the burning brotherhood of man to which religion had barred the door.

The reign of terror in all its forms was ended.

In the vain hope of erasing their memory, I will name the things we feared:

fear of prejudice, fear of public opinion, fear of persecution and general disapproval

fear of being abandoned by God and by a society that invariably leaves us to our lonely fate

fear of ourselves, of our brothers, of poverty

fear of the established order, of the mockery of justice

fear of new relationships

fear of the irrational

fear of needs

fear of the floodgates that open onto our faith in man, of the society of the future

fear of anything that could inspire in us a transforming love

blue fear - red fear - white fear: each one another link in the chain that binds us.

From the reign of debilitating fear we entered the age of anguish.

We would have to be made of stone to remain indifferent to the underlying sadness of those who have put on a false air of gaiety, a psychological reflex that takes the form of the most cruel extravagances - the cellophane wrapping with which we try to cover up our current agonizing despair. How can we not cry out in protest when we read the news of this horrible collection of lampshades pieced together from tattooed skin stripped from the flesh of miserable prisoners at the request of some elegant lady? How can we stifle our groans at the interminable list of concentration camp atrocities? How can we keep our blood from curdling at descriptions of Spanish dungeons, unjustifiable reprisals, cold-blooded acts of vengeance? How can we fail to tremble in the face of the relentless reality of science?

The reign of overpowering anguish is succeeded by the reign of nausea.

We have been disheartened by man's apparent inability to right these wrongs. By the futility of our efforts, by the vanity of our hopes of old.

For centuries, the generous fruits of poetic activities have been a tragic failure from a social point of view, at first violently tossed aside by a social structure that then makes a tentative effort to reuse them by distorting them irrevocably in the name of integration and false assimilation.

For centuries, splendid revolutions fought by people who believed in them utterly have been crushed after one brief moment of delirious hope in their barely interrupted slide toward inevitable defeat:

the French revolutions

the Russian revolution

the Spanish revolution

which ended as an international free-for-all, despite the vain hopes of countless simple souls throughout the world.

Once again, fatality was stronger than generosity.

How can we not be sickened by the rewards given for shocking acts of cruelty, to liars, to forgers, to manufacturers of useless products, to plotters of intrigue, to the openly self-seeking, to the false counsellors of humanity, to those who pollute the fountain of life? How can we not be nauseated by our own cowardice, our helplessness, our weakness, our lack of understanding? By our own ill-starred loves ... In the face of our continuing preference for cherished illusions rather than objective enigmas.

What makes us so efficient at imposing on ourselves this evil of our own making, if not our determination to defend the civilization that ordains the destinies of our leading nations?

The United States, Russia, England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain: all of them the sharp-toothed heirs of the same Ten Commandments, the same gospel.

The religion of Christ has dominated the world. See what it has turned into: sister faiths have now begun to exploit each other.

Suppress the forces that encourage competition in natural resources, prestige and authority, and they will be in perfect agreement. But no matter which one were to gain supremacy over the world, the general result would be essentially the same; only the details would be different.

Christian civilization is coming to an end.

The next world war will bring about its total collapse by eliminating all possibility of international competition.

Even those who refuse to see will be unable to ignore its moribund condition.

The decomposition that began in the 14th century will nauseate even the least sensitive.

Its despicable exploitation, maintained so efficiently for so many centuries at the cost of life's most precious qualities, will finally be revealed to its multitude of victims - submissive slaves who, the more wretched they were, the harder they fought to defend it.

But there will be an end to torture.

The decline of Christianity will bring down with it all the people and all the classes that it has influenced, from the first to the last, from the highest to the lowest.

The depth of its disgrace will be equal to the height of its success in the 13th century.

In the 13th century, once the limits allowed for the evolution of moral education and relationships that had originally been inclusive were achieved, intuition gave way to reason. Gradually the act of faith was replaced by the calculated act. Exploitation was born in the very heart of religion when it began to take advantage of existing feelings that had no other outlet, by the rational interpretation of holy texts for the purpose of maintaining the supremacy that it had once been freely given.

This rational exploitation spread slowly to all levels of social activity: maximum returns were demanded.

Faith sought refuge in the hearts of the people and became their last hope of reward, their only consolation. But there, too, hope began to fade.

Among the learned, mathematics replaced the outmoded traditions of metaphysical speculation.

The spirit of observation succeeded the spirit of transfiguration.

Method pushed our boundaries even further. Decadence became convivial and necessary: it favoured the creation of agile machines that moved at frightening speeds, enabling us to harness the power of our tumultuous rivers while we wait for the planet to blow itself up. Our scientific instruments are wonderful devices for studying and controlling things that otherwise would be too small, too fast, too vibrant, too slow or too large for us to comprehend. Our rational thinking has unlocked all the gates of the world, but at the price of our unity.

The growing chasm between spiritual and rational powers is stretched almost to the breaking point.

Material progress, that carefully controlled privilege of the affluent, did bring about political development - first with the help of religious authorities and later without them - but did nothing to renew the foundations of our sensitivity, of our subconscious, or to facilitate the full emotional development of the masses, the only thing that would have allowed us to escape from the deep rut of Christianity.

The society that was born of faith will die at the hands of reason: THE INTENTION.

The fatal disintegration of our collective moral strength into strictly individual and sentimental power has undermined the once formidable shield of abstract knowledge behind which society takes cover to enjoy its ill-gotten gains at leisure.

It took the last two wars to achieve this absurd result. The horror of the third war will be decisive. We are on the brink of a D-day of total sacrifice.

The rats are already fleeing a sinking Europe by crossing the Atlantic. However, events will eventually overtake the greedy, the gluttonous, the sybarites, the unperturbed, the blind and the deaf.

They will be mercilessly swallowed up.

A new collective hope will dawn.

It is already demanding the passion of exceptional insights, anonymous union in renewed faith in the future, in the future collectivity.

The magical harvest magically reaped from the unknown lies ready in the field. It was gathered by all the true poets. Its powers of transformation are as great as the violence practised against it, as its continued resistance to attempts to make use of it (after more than two centuries, there is not a single copy of the Marquis de Sade to be found in our bookshops; Isidore Ducasse, dead for more than a century, a hundred years of revolution and slaughter, is still too strong for queasy contemporary stomachs, even those accustomed to present-day filth and corruption).

None of these treasures is accessible to our society as yet. They are being preserved intact for future use. They were created spontaneously outside of and in spite of civilization. Their effects on society will be felt only when our present needs are clear.

Meanwhile, our duty is plain.

We must abandon the ways of society once and for all and free ourselves from its utilitarian spirit. We must not willingly neglect our spiritual side. We must refuse to turn a blind eye to vice, to scams masquerading as knowledge, as services rendered, as payment due. We must refuse to live out our lives in the only plastic village, a fortified place but easy enough to escape from. We must insist on having our say - do what you will with us, but hear us you must - and refuse fame and privilege (except that of being heard), which are the stigma of evil, indifference and servility. We must refuse to serve, or to be used for, such ends. We must refuse all INTENTION, the harmful weapon of REASON. Down with them both! Back they go!

Make way for magic! Make way for objective enigmas! Make way for love! Make way for what is needed!

We accept full responsibility for the consequences of our total refusal.

Self-interested plans are nothing but the stillborn children of their parents.

Passionate actions have a life of their own.

We are happy to take full responsibility for tomorrow. Rational effort can only release the present from the constraints of the past when it stops looking back.

Our passions will spontaneously, unpredictably, necessarily forge the future.

Although we must acknowledge the past as the birthplace of the future, it is far from sacred. We owe it nothing.

It is naive and unhealthy to think that, because historical persons and events happen to be famous, they are endowed with special qualities to which we ourselves cannot aspire. These qualities are indeed out of the reach of facile academic affectedness, but anyone who responds to the deepest needs of his or her being or recognizes his or her new role in a new world will attain them automatically. This is true for anyone, at any time.

The past must no longer be used as an anvil for beating out the present and the future.

All we need from the past is what we can put to use today. The present will inevitably give way to the future.

We need not worry about the future until we happen upon it.

THE FINAL RECKONING

The social establishment resentfully views our dedication to our cause, the outpouring of our concerns and our excesses, as an insult to their indolence, their smugness, and their devotion to the material pleasures of a life that has long ceased being generous or full of hope and love.

The friends of those in power suspect us of promoting the "Revolution." The friends of the "Revolution" think that we are nothing but malcontents: " ... we are protesting against the status quo, but only because we want to transform it, not because we want to transform it into something."

However tactfully it may be worded, we think we get the point.

It is all a matter of class.

The friends of the Revolution have suggested that it is our naive intention to try to "transform" society by replacing the men in power with similar men. So, obviously, why not choose them?

Because they are not of the same class! As if a change in class implied a different civilization, different aspirations, different expectations!

They would be happy to organize the proletariat in return for a regular salary plus a cost-of-living allowance, and they are absolutely right. The only trouble is that, as soon as victory is firmly within their grasp, in addition to the small salaries they are currently receiving, they will keep squeezing more and more from the same proletariat, just as the bureaucracy does now, in the form of surcharges and the right to remain in power over long periods, with no discussion permitted.

Nevertheless, we recognize that they are part of our history. Health can come only after the greatest excess of exploitation.

These men are this excess.

They are fated to do this without anyone's assistance. Their plunder will be plentiful. We have already refused to let them share it with us.

Here is where our "guilty abstention" comes into play.

We leave the rationally ordained (like everything else that lies at the complacent heart of decadence) rush for the spoils to you. As for us, give us spirited action; we are risking all for our total refusal.

(We cannot help it that the various social classes that have succeeded one another in governance over the people have been unable to resist the lure of decadence. We cannot help it that what we know of our history teaches us that only the full development of our faculties, followed by the entire renewal of our emotional resources, can lead us around this impasse and place us on the road to a civilization that is eager to be born.)

All those who hold power or aspire to it would be quite happy to grant our every wish, if only we were willing to let them use their scientific regulations to twist our activities.

Success will be ours if we close our eyes, stop up our ears, roll up our sleeves and fling ourselves pell-mell into the fray.

We prefer our cynicism to be spontaneous, without malice.

Kindly souls smile somewhat at the lack of financial success of joint exhibitions of our work. It gives them a feeling of satisfaction to think that they were the first to be aware of its small market value.

If we do keep putting on exhibitions, it is not with the naive hope of becoming rich. We know there is a world of difference between us and the wealthy. They would never run the risk of this type of incendiary contact with impunity.

The only sales we have had in the past have been to people who did not understand the situation.

We hope that this text will avoid any such misunderstandings in the future.

If we work with such feverish enthusiasm, it is because we feel a pressing need for unity.

Unity is the road to success.

Yesterday we stood alone and irresolute.

Today we form a strong, steady group whose ramifications are already pushing the limits.

We also have the glorious responsibility of preserving the precious treasure that has been left to us. This is also part of our history.

Its tangible values must constantly be reinterpreted, be compared and questioned anew. This is an exacting, abstract process that requires the creative medium of action.

This treasure is our poetic resources, the emotional renewal that will inspire the generations of the future. It cannot simply be passed down but must be ADAPTED, else it will be distorted.

We urge all of those who yearn for adventure to join us.

Within the foreseeable future, we expect to see people freed from their useless chains and turning, in the unexpected manner that is necessary for spontaneity, to glorious anarchy to make the most of their individual gifts.

Meanwhile we must work without respite, united in spirit with those who long for a better life, without fear of long delays, regardless of praise or persecution, toward the joyful fulfilment of our fierce desire for freedom.

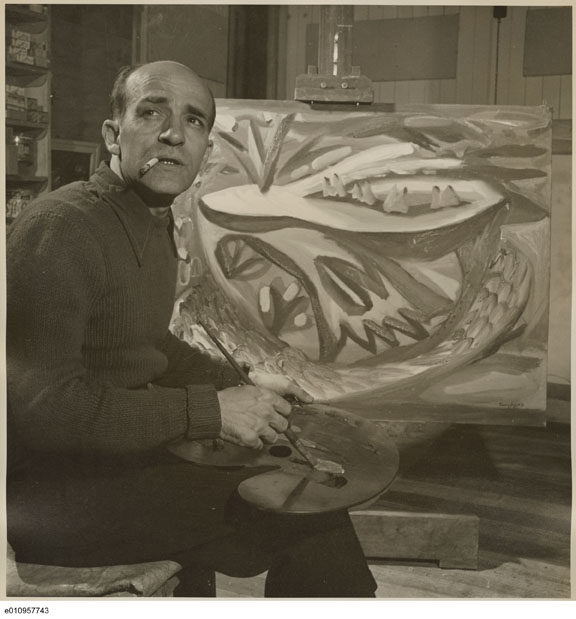

Magdeleine Arbour, Marcel Barbeau, Bruno Cormier, Claude Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Muriel Guilbault, Marcelle Ferron-Hamelin, Fernand Leduc, Thérèse Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Maurice Perron, Louise Renaud, Françoise Riopelle, Jean Paul Riopelle, Françoise Sullivan.

See also Refus global.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom