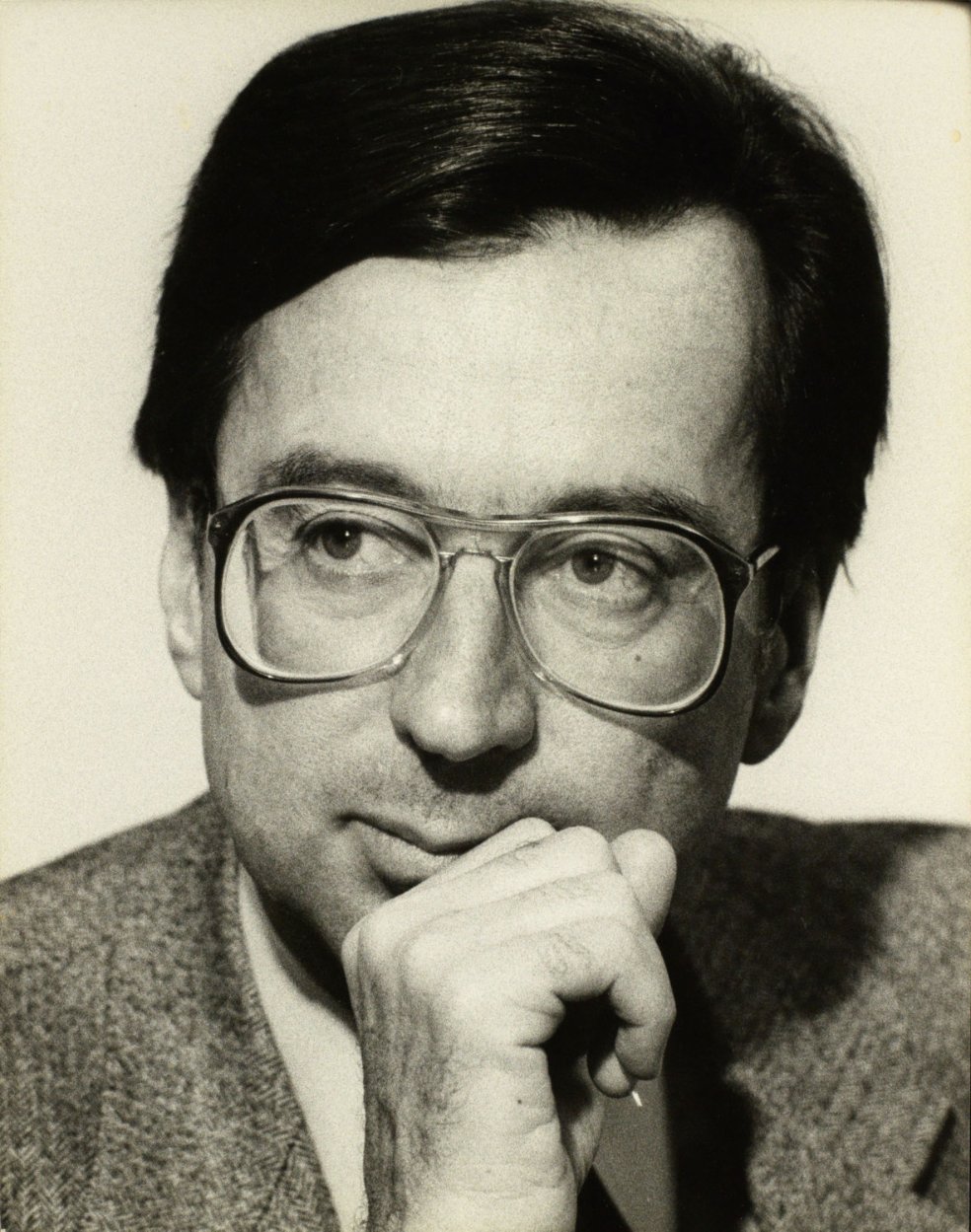

Jacques Parizeau, GOQ, economist, professor, senior public servant, politician and premier of Québec (born 9 August 1930 in Montréal, QC; died 1 June 2015 in Montréal, QC). Jacques Parizeau was one of the most prominent leaders of modern-day Québec and a steadfast champion of the Québec sovereigntist movement.

Education and Early Career

Jacques Parizeau was born into an upper-class family in Montréal, the son of insurer, businessman and historian Gérard Parizeau and his wife Germaine Biron. Parizeau studied at the Collège Stanislas in Outremont and at the École des hautes études commerciales (HEC Montréal), from which he graduated in 1950. He continued his studies in Paris at the Institut d’études politiques and at the Faculté de droit de Paris (1952). In 1955, at the age of 24, he received a PhD in economics from the London School of Economics.

Upon returning to Québec, Parizeau taught at HEC Montréal from 1955 to 1976, and served as head of the Department of Applied Economics from 1973 to 1975. He was consulted by various Québec ministers and was one of the architects of the Quiet Revolution of the early 1960s. From 1961 to 1969, he was the economic and investment advisor to the premier of Québec and the Cabinet. He helped nationalize hydroelectricity and establish a new bargaining system in the Québec public service. He also helped to create the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, a key contribution to the modernization of the province’s economy.

Parliamentarian and Minister in the Lévesque Government

Parizeau officially joined the Parti Québécois (PQ) in 1969. He explained his choice to support the party by stating his conviction that strong Québec and Canadian governments could not both operate in the same country. He never deviated from his separatist aim for the duration of his political career. He was Minister of Finance from 1976 to 1984 under René Lévesque’s successive governments, but resigned because he was critical of Lévesque’s federalist sentiments. Lévesque favoured an attempt at reworking Québec-Canada relations under the beau risque strategy (see Sovereignty-Association; Constitutional History).

In 1988, Jacques Parizeau replaced Pierre Marc Johnson as leader of the Parti Québécois, a sign that his views were gaining ground within the party. He made independence a top priority for the party again, and in so doing set his party up for an arduous period of being in the opposition. The following year, Robert Bourassa and Brian Mulroney negotiated a new constitutional agreement between Canada and Québec, known as the Meech Lake Accord. When Jacques Parizeau was appointed leader of the PQ, as the accord was reaching its final ratification, influential beau risque supporters joined the Conservative party in Ottawa (notably Lucien Bouchard), and the federalist movement seemed to be gaining momentum in Québec.

In the 1989 provincial elections, despite winning 40 per cent of the vote, the Parti Québécois won only 29 seats and was once again relegated to opposition status. In June 1990, the Meech Lake Accord failed, and the alliance between beau risque supporters and Canadian federalists was broken. Lucien Bouchard left the Mulroney government to create a federal separatist party, the Bloc Québécois. Robert Bourassa refused to take part in the First Ministers Conferences and threatened to hold a referendum on Québec sovereignty if the rest of Canada could not propose an acceptable constitutional amendment before the summer of 1992. The first ministers came to an agreement in August of that year with a new constitutional amendment, the Charlottetown Accord. The accord was rejected following a national referendum held on 26 October 1992. Jacques Parizeau led the Québécois “No” vote to victory, joining five other provinces that opposed the accord.

Election as Premier of Québec and the 1995 Referendum

In 1994, Jacques Parizeau was elected Premier of Québec, receiving 45 per cent of the vote and winning out over Robert Bourassa’s successor, Daniel Johnson (younger). Although the vote count was close, the Parti Québécois won 77 of the 125 seats in the National Assembly. The federal sovereigntists of the Bloc Québécois, led by Lucien Bouchard, had won seats in over two thirds of Québec ridings the previous year. Jacques Parizeau proclaimed that the conditions were right for him to carry out his promise of holding a referendum in the year following his election. But the momentum that the sovereigntist movement had gathered following the failure of the Meech Lake Accord had begun to dwindle. At the beginning of the referendum campaign, the Yes vote was more than 10 points behind the No vote. Midway through the campaign, in a last effort to reverse this trend, Jacques Parizeau agreed to step down and allow Lucien Bouchard, who was very popular among Québec voters, to take over managing the Yes campaign.

On 30 October 1995, the Yes vote won 49 per cent of the vote, falling a few tens of thousands of votes short of a majority. The night of the referendum, a visibly bitter Jacques Parizeau stated that he had been defeated by the financial influence of the opposing side and a strong mobilization of ethnic communities against the Yes vote, a statement for which he was severely criticized. He resigned the next day.

Controversy

Following his resignation, Jacques Parizeau took on the role of leader of the sovereigntist movement, attempting to breathe new life into the effort, in particular by leading a think tank on the subject within the Bloc Québécois. He regularly commented on Québec current affairs and criticized the Bouchard government’s obsession with a zero deficit and the Parti Québécois’ ambiguous stance on the referendum issue. He was even critical of his successors, and his commentary earned him the nickname belle-mère, literally “mother-in-law.” A devoted democrat, Jacques Parizeau believed so deeply in the importance of debate that he would even criticize his own party. A few months before he died, he declared that sovereigntists were faced with “un champ de ruines” (a field of ruins) following the defeat of the Parti Québécois led by Pauline Marois in the election on 7 April 2014. Just before the 2012 election he openly supported the new Option nationale party, led by Jean-Martin Aussant, over his old party.

Jacques Parizeau never apologized for the controversial remark he made the night of the 1995 referendum. The following day in his resignation speech he did, however, acknowledge that he had not expressed his disappointment well. However, if his statement could be interpreted as a reference to a nationalist identity, it goes against the vision of civic nationalism that he always spoke in favour of for a sovereign Québec — namely, a society that is modern, secular, pluralist and open to the world (see Francophone Nationalism in Québec). He was also one of the strongest critics of the Québec values charter proposed by PQ minister Bernard Drainville, because he deemed that the charter was too prohibitive and that it should have instead been limited to the recommendations given in the Bouchard-Taylor report.

Legacy

Jacques Parizeau was an important architect of modern-day Québec who gave the province some of its most powerful economic engines. Although his contributions to economic development, nation building and political debate are widely acknowledged in Québec, he is remembered in the rest of Canada for a period of political divisiveness and constitutional disruption.

He has received numerous awards and honours in recognition of his academic and political careers. In 2004, filmmaker Francine Pelletier produced a documentary about him titled Monsieur. The day after his death, the National Assembly announced that a state funeral would be held in his honour and that the main building for the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec would be named Édifice Jacques-Parizeau.

Jacques Parizeau married Polish writer Alice Parizeau (née Alicia Poznanska) in 1956. He remarried in 1992. His second wife, Lisette Lapointe, was a member of the Parti Québécois from 2002 to 2012 and became mayor of Saint-Adolphe d’Howard in 2013. The Jacques Parizeau archives are held at the Centre d’archives du Vieux-Montréal of Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Honours and Awards

Commander of the Legion of Honour, French government (2000)

Prix Louis-Joseph-Papineau, Rassemblement pour un pays souverain (2006)

Grand Officer of the National Order of Québec (2008)

Prix Richard-Arès for Best Essay Published in Québec (for La souveraineté du Québec: Hier, aujourd’hui et demain) (2010)

Honorary doctorate, Université de Montréal (2014)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom