Terminology

There is debate about the terms enslavement and enslaved people, on one hand, and slavery and slaves on the other. Many authors and historians use both sets of terms, which have similar meanings but can represent different perspectives on historical events. For example, slave is used to describe a person’s property. It is a noun that critics of the term say reduces a person to a position they never chose to be in. The term enslaved describes the state of being held as a slave. Historians who prefer enslaved person explain that it makes it clearer that enslavement was imposed on people against their will. They also mention that adding the word person brings forward the humanity of the people the term describes.

Some historians continue to use the terms slave and slavery, without adding person, arguing that the terms are clearer and more familiar. They argue that adding the word person implies a level of autonomy that enslavement took away from people.

Background

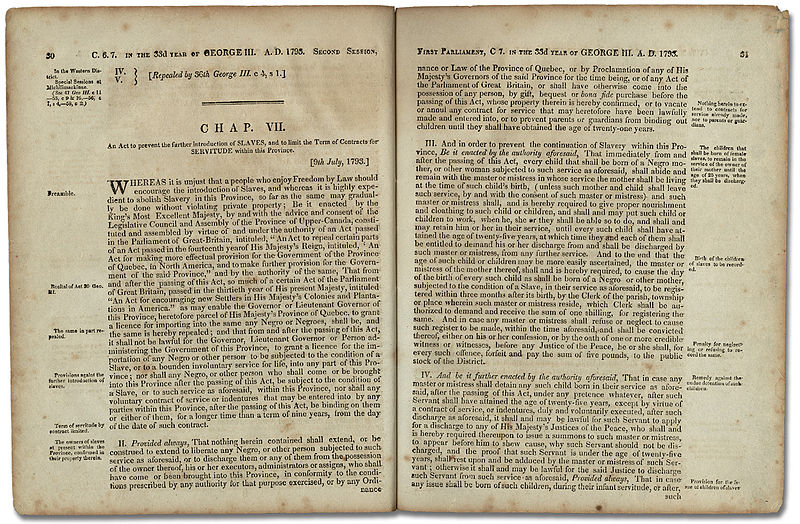

More than 4,000 Indigenous and Black people were enslaved in Canada from the colonization of New France in the early 1600s until 1834, when the Slavery Abolition Act came into effect throughout the British Empire, including British North America (see: Slavery of Indigenous People; Black Enslavement). In the United States, it remained legal to enslave people until 1865, but a growing divide emerged between abolitionist Northern states and the South, where slavery drove the plantation economy.

By the mid-1800s, anti-slavery societies had existed for years in the United States and United Kingdom, but the movement had not yet taken root in Canada. Among early efforts in this country were two short-lived organizations formed with the support of American activists. The first anti-slavery society was founded in 1827 by members of the Black community in Windsor; the second, called the Upper Canada Anti-Slavery Society, was active in the late 1830s under the leadership of Reverend Ephraim Evans, a White Methodist minister.

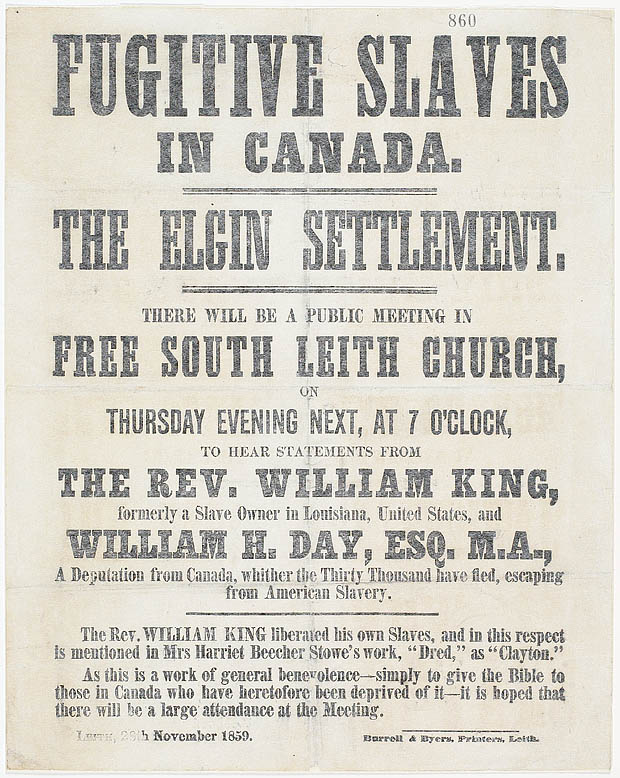

In 1850, the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which legalized the capture of those who had escaped enslavement in the North and their return to enslavers in the South. The law also prohibited citizens from helping fugitives reach freedom. Its enactment spurred the migration of 15,000 to 20,000 African American refugees to Canada in the decade that followed. Some found their own way across the border, while others came via the Underground Railroad.

The refugees’ plight generated public discussion in Canada. In 1850, it was the subject of a sympathetic meeting at the Mechanics’ Institute in Toronto and the subject of pro-abolition editorials in the Globe newspaper, edited by Gordon and George Brown (see also: George Brown of the Globe; Globe and Mail). Some reactions were far from sympathetic, however. Historian Robin Winks cites “growing evidence of organized, group prejudice in Canada West,” including petitions and campaigns against Black settlements near Chatham, an important terminus of the Underground Railroad (see also: Prejudice and Discrimination; Racism). Not far away, in Colchester, White men had physically blocked Black residents from voting in an 1848 election (see Black Voting Rights).

Formation

The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada was formed on 26 February 1851 in a public meeting chaired by the mayor at Toronto City Hall. Its first and only president was Presbyterian minister Michael Willis. The founding committee included several faith leaders in addition to Willis, as members of some Christian denominations (e.g., Baptists, Congregationalists, Methodists, Presbyterians and Quakers) were active in the abolition movement. Other prominent members were publisher George Brown and future premier of Ontario Oliver Mowat.

Black members of the executive included Wilson Ruffin Abbott, businessman and father of Anderson Abbott; Henry Bibb, editor of Voice of the Fugitive; and Albert Beckford Jones, a grocer. All three were born in the US (Jones and Bibb had been enslaved) and later settled in Canada. The executive included 14 local vice-presidents appointed to head chapters throughout Canada West. Jones and Bibb directed the London and Windsor chapters, respectively.

At its inaugural meeting, the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada adopted a constitution, bylaws and four resolutions. These resolutions condemned enslavement as inhumane, indicted the United States for not outlawing the practice, sympathized with the efforts of American abolitionists and defined the society’s objective:

…to aid in the extinction of slavery all over the world by means exclusively lawful and peaceable, moral and religious, such as by the diffusing of useful information and argument, by tracts, newspapers, lectures and correspondence, and by manifesting sympathy with the houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil.

The society was structured into three levels: office bearers, committee members and subscribers. The first two classes acted as agents of the organization, while subscribers supported it by paying annual dues.

Inaugural Year: 1851

As editor of the Globe — one of British North America’s leading newspapers in the 1850s — George Brown reported extensively on the society’s formation, advocated for abolition and raised awareness on behalf of refugees. He also republished materials from other anti-slavery newspapers.

The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada fostered close ties with American and British counterparts through correspondence and meetings. In April 1851, American orator Frederick Douglass, who had himself escaped enslavement, spoke at St. Lawrence Hall in Toronto as part of a lecture series sponsored by the society. In May, its president, Michael Willis, addressed the annual gathering of the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York City, where he reported on the situation in Canada.

That same year, the society launched aid programs and supported other relief organizations in the province. It also established a night school to train a small group of refugees in farming. The first step to ensuring the well-being and independence of these new arrivals, it believed, was to provide the economic stability and resources they required to focus on securing employment.

On the subject of education, the society took a firm position against segregated schools. Its first annual report noted that the quality of education at separate schools for Black students was inferior and that teachers were poorly paid. Henry Bibb viewed integration as key to the success of Black communities in Canada, and George Brown used his position in the press to oppose segregation.

Canada’s governor general, Lord Elgin, sought the Anti-Slavery Society’s advice on a proposal to direct the resettlement of Black people outside North America, namely to the West Indies. The society sided with a resolution of the 1851 North American Convention of Colored Freemen (held at Toronto’s St. Lawrence Hall) in opposing the idea, which it viewed as an effort by defenders of slavery to rid North America of free Black people.

Role of Women’s Organizations

Although the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada was composed of men, much of the grassroots work essential to its mission was administered by women. Women’s organizations, typically led by wives of the society’s committee members and local vice-presidents, collected and distributed money and clothing for fugitives, in addition to campaigning for abolition in the US.

In Toronto, for example, refugees in need could seek assistance from the Toronto Ladies’ Association for the Relief of Destitute Coloured Fugitives, which assessed applications and distributed funds in the amount it considered appropriate to each case. The Ladies’ Association included treasurer Agnes Willis (wife of Anti-Slavery Society president Michael Willis) and corresponding secretary Isabella Henning (wife of secretary Thomas Henning and sister of George Brown). Of its 40 members, the only known Black member was a woman named Ethalinda Lewis, about whom few details are available.

Like its parent society, the Ladies’ Association was active in the international abolition movement. It gathered almost 14,000 signatures for the Stafford House Address of 1853. This petition, signed by more than half a million women throughout the British Empire, appealed to women in the United States to help end enslavement in their country. Historian Karen Leroux notes that 14,000 signatures represents a remarkable achievement, as Toronto’s total population was only about 30,000 people in 1851. The campaign sparked conversations about enslavement in circles where it was seldom discussed, and it likely extended beyond Toronto.

Reach

In its early years, the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada also organized public meetings throughout Canada West, booking such prominent abolitionist speakers as Samuel May, George Thompson and Reverend Jermain Wesley Loguen. Reverend Samuel Ringgold Ward, a free Black American who had fled to Toronto to avoid arrest for his participation in the Underground Railroad, embarked on particularly fruitful speaking tours after being named to the society’s executive in late 1851. He helped establish chapters throughout the province — in Grey County, Hamilton, Kingston and Windsor. In 1853–54, he travelled to England on behalf of the society, where he raised £1,200 and spoke at meetings of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

Although it counted fewer than 200 members at its peak, the Canadian society extended its reach as far as Montreal in Canada East. Newspaper editor John Dougall and flour merchant D.S. Janes, both White residents of that city, were active members of the executive committee. Dougall often attacked slavery in his publication, the Montreal Witness.

Final Years

The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada’s activities slowed in the mid-1850s and, by the last years of the decade, focused more on relief work than on direct abolitionist action.

The Canadian organization was less involved in legal battles than were its counterparts in the United States. In 1860–61, however, it participated in the high-profile case of a formerly enslaved man named John Anderson, arrested in Canada on the charge of killing an enslaver in Missouri. The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada fought Anderson’s extradition to the United States to face trial. He was eventually released due to an error in the arrest warrant.

Sometime after the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 — which ultimately led to the formal end of slavery in the United States in 1865 — the Canadian society ceased its activities. Many Black settlers returned to their home states, where they were now free.

Impact and Limitations

The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada helped spread abolitionist sentiment in Canada while providing aid and advocacy for refugees of the US slave trade. In the United States, a much larger anti-slavery movement was already well established by the 1850s. The Canadian organization was therefore limited in its opportunities to bring about change south of the border. It did, however, help shape Canadian public opinion in the years leading up to the American Civil War, during which an estimated 40,000 Canadians fought on the side of the abolitionist North.

While the society provided financial support to hundreds of people fleeing enslavement in an attempt to set them on the path to self-sufficiency, historians have noted that its aid efforts were at best tainted by a paternalistic attitude, and at worst by racism. Robin Winks writes that the society’s White members revealed “the quiet arrogance of those who feel that they have all to give to an underprivileged group and nothing to learn from it.”

Black member Samuel Ringgold Ward criticized the unwillingness of White abolitionists (who formed the majority of the society) to recognize slavery and racism as separate issues. Ward saw that freedom would not guarantee equality for Black persons, and he suspected that few abolitionists in Canada were willing to work for equal rights. His outspokenness on these points made him unpopular among his comparatively conservative fellow members, who perhaps considered their work done when abolition was achieved. But Ward’s view proved well founded: anti-Black racism and discrimination persisted long after the abolition of slavery — for instance, in a proposed ban on Black immigration to Canada in 1911 — and it continues in various forms today.

As much as the Anti-Slavery Society benefitted from its association with newspapers (e.g., the Globe) and Christian denominations (e.g., the Presbyterian Church), it met with resistance and apathy from other publications and communities. For example, The Patriot and The Church were critical of its mission, the latter arguing that it was not Canada’s responsibility to condemn “compulsory labour.” The society urged greater participation from churches, but was frustrated by those Christians who would not take a clear stance against slavery or who continued to be friendly with American bodies that supported it. This lack of wider traction for the cause, paired with personal and ideological conflicts within the Canadian abolitionist movement, limited the society’s impact.

Several other factors impeded its work. Widespread anti-Americanism in Canada at the time meant that much of the public could not be moved to side with a cause south of the border. The organization also lacked money, subscribers and direct links to political parties with the power to shape policies in Canada. Finally, some members were uncomfortable with the overlap between abolitionism and the women’s rights movement, which had grown along with anti-slavery activism in the United States.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom