More than 400 million years ago, during the Silurian and Devonian periods, geological processes of plate tectonics slowly carried what is now Canada away from the Southern Hemisphere and across the equator. At that time, with Canada in the tropics, the earliest land plants were establishing the first vegetation and preparing the way for colonization of land by animals. This episode in earth history was transformational: barren landscapes of earlier times giving way to the rich tapestry of terrestrial ecosystems that is our home.

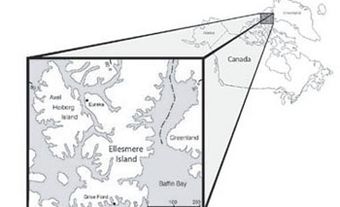

Early land plants have long been known from Eastern Canada, thanks to pioneering work by Sir J. William Dawson, father of Devonian palaeobotany and principal of McGill University from 1855 to 1893. But this record poorly represented the earliest phase of land colonization. The first hint that more ancient evidence was preserved in Canada's remote Arctic islands came from fragments recovered on Bathurst Island during the 1955 Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) expedition to Arctic Canada, known as "Operation Franklin." Dr Francis Hueber, then of the GSC, first described these fossils in 1972, but nothing more was heard until the GSC renewed interest in the island in the 1990s. Exploration of Bathurst Island from 1993-96 yielded the most extensive record of very early land plants from North America and one of the finest collections in the world.

Most fossil plants of Bathurst Island are of "Pragian" or basal Devonian age (from about 411 to 407 million years ago), but some extend into the Late Silurian (from 423 to 416 million years ago) and figure among the oldest known land plants. It was an alien world. Plants at that time were small, little more than ankle high, and reproduced only by spores as seeds had not yet evolved. Most had no leaves but only green stems, and roots were only beginning to form as a distinct organ system. All plants entirely lacked what we call wood and appear to have been "herbaceous," soft and vulnerable. It is likely that they did not spread far beyond favourable moist habitats. Localization on the landscape probably explains their worldwide rarity.

The majority of the Bathurst flora belonged to an extinct group known as the "zosterophylls," distantly related to the living club-mosses (Lycopodium), a surviving member of a very ancient lineage known as the "lycophytes." Club mosses are found throughout the world, including Canadian forests, and if found, on hands and knees, can inspire a glimpse of a primeval world. Most of the Bathurst Island zosterophylls were naked stems about 10-20 cm tall, arising in tufts, and terminating in a cluster of small sporangia. One type, named Bathurstia, was a giant of its age, with stems up to one cm wide and towering to heights of 30 cm. A robust and aggressive invader, its stems freely produced plantlets, miniature new plants, as it scrambled across the ground. A related lycophyte in the Bathurst flora is Drepanophycus, one of the first plants with true leaves. The stems, covered with fine, bristlelike leaves, were too weak to support themselves and draped across the ground.

Although the lycophytes dominated the early flora of Bathurst Island, this group is now dwarfed by conifers, flowering plants and ferns, the descendants of a separate lineage of plants that shared ancestry with the lycophytes when life first emerged on land. This other group, the "euphyllophytes," was originally rare and inconsequential. A visitor strolling through the ancient Bathurst landscape could not have predicted that it would feature predominantly in Earth's future vegetation. But the euphyllophytes emerged from obscurity to evolve into the great diversity we see today, driving the lycophytes to the brink of extinction. In the evolution of life on Earth, we often see such turnovers in flora and fauna, when the dominant forms of life dwindle and vanish to be replaced by the descendants of something altogether unexpected.

See also Palaeontology.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom