Nearly 2,000 unprepared Canadian troops fought bravely to defend the British colony against a formidable Japanese invasion force. On Christmas Day, 75 years ago, the fighting ended... but the struggle for survival had only just begun.

"The story, however, is not about how the Canadians were defeated. It’s about how they fought and how they behaved against impossible odds. And it’s about the mettle they showed when it was apparent that there was no hope and there was no possibility of a successful outcome. They never surrendered and they fought like tigers." — George MacDonell

Why Hong Kong?

Canada entered the Second World War against Germany in 1939, but Canadian soldiers saw little action in the early years. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was worried that committing troops to battle overseas might require conscription and ignite conflict between French- and English-speaking Canadians.

By 1941, English Canada was clamouring for King to do more. So Ottawa agreed to a British request for troops to help bolster the small colony of Hong Kong. Battalions from two under-trained units — the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada (from Québec City) — were dispatched in November for what all expected would only be garrison duty, in a quiet outpost of the Empire.

War in the Pacific

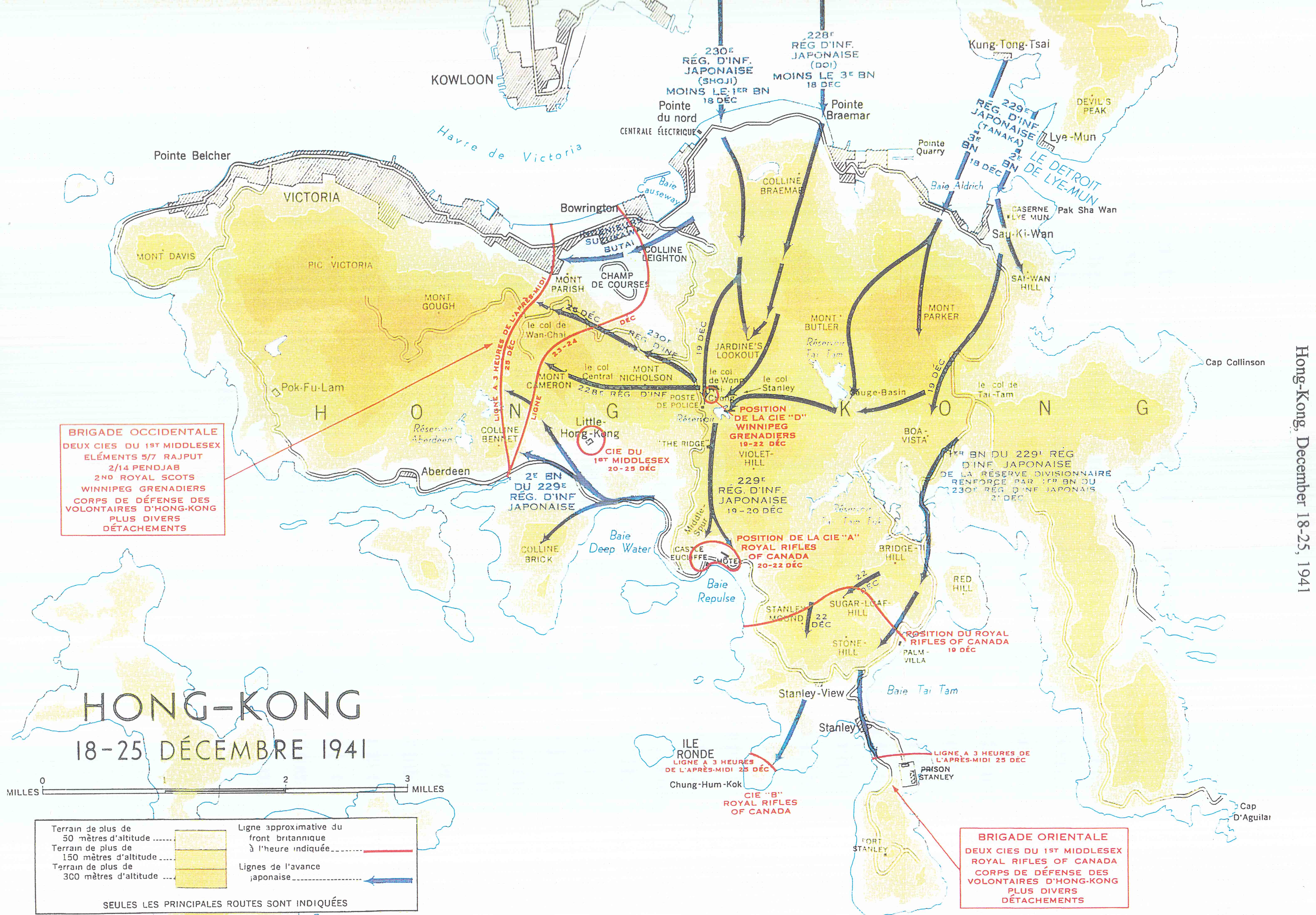

Japan had waged war in China since 1937, but it had avoided open hostilities against the West. However, on 7 December 1941, three weeks after the Canadians arrived in Hong Kong, Japan stunned the world by attacking the United States’ naval fleet at Pearl Harbor. Six hours later, the battle-hardened troops of the Japanese 38th Division attacked Hong Kong with overwhelming force.

Fourteen Days of Fighting

“I never surrendered. The governor of the island surrendered the island and I was ordered by my officer to lay down my arms. I never put up my hands.” — Bill Willington MacWhirter

Canadian, British and Indian troops fought hard to resist the Japanese assault. On 11 December, the men of "D" company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers became the first Canadian Army troops to engage in combat in the war. Short of water and ammunition — and pounded by the enemy’s superior artillery and command of the skies — the defenders held on for 14 days, refusing Japanese demands for surrender. On Christmas Day, the British governor finally surrendered, leaving thousands of Allied soldiers, and the colony's 1.6-million residents at the mercy of the Japanese.

Among the Canadian troops, 290 had been killed and 493 wounded in the battle.

Acts of Valour

The fighting had inspired numerous acts of personal bravery.

On 19 December, Company Sergeant-Major John Osborn of the Winnipeg Grenadiers threw himself on a Japanese grenade that had been tossed into his men's position. He was killed instantly, but he saved the lives of several Canadian soldiers. Osborn was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

The same day, Brigadier J.K. Lawson, the senior Canadian commander, had his headquarters surrounded by Japanese attackers firing almost point-blank into his bunker. Lawson announced he was going outside “to fight it out” with the enemy. The Japanese would later make note of his heroic death.

Prisoners of War

After the battle, nearly 1,700 Canadian soldiers became prisoners of war (POW) — first at camps in Hong Kong and later in Japan. Years of hardship followed, as they endured beatings, hard labour and inadequate diets. Hundreds of the Canadians died of illness, or from slow starvation in Japanese camps.

Veteran Story: George MacDonell

“I spent the first year or so in Hong Kong and then I was shipped to Japan. We were in Yokohama, Japan, in a camp called Camp 3B, and we were working in Japan’s largest shipyard, a vitally important war industry building much needed Japanese freighters and naval vessels.

“In order to strike back at the Japanese, these two young men, Staff Sergeant Clark and Private Cameron, decided that they would commit sabotage through arson… And they did that by starting a fire… under the blueprint factory and the place where the wooden forms are patterned, it’s called the pattern shop. And since in those days there was no electronic storage of information in computers, once you burned the blueprints and the patterns… there was no way you could build a ship or do anything in that shipyard.”

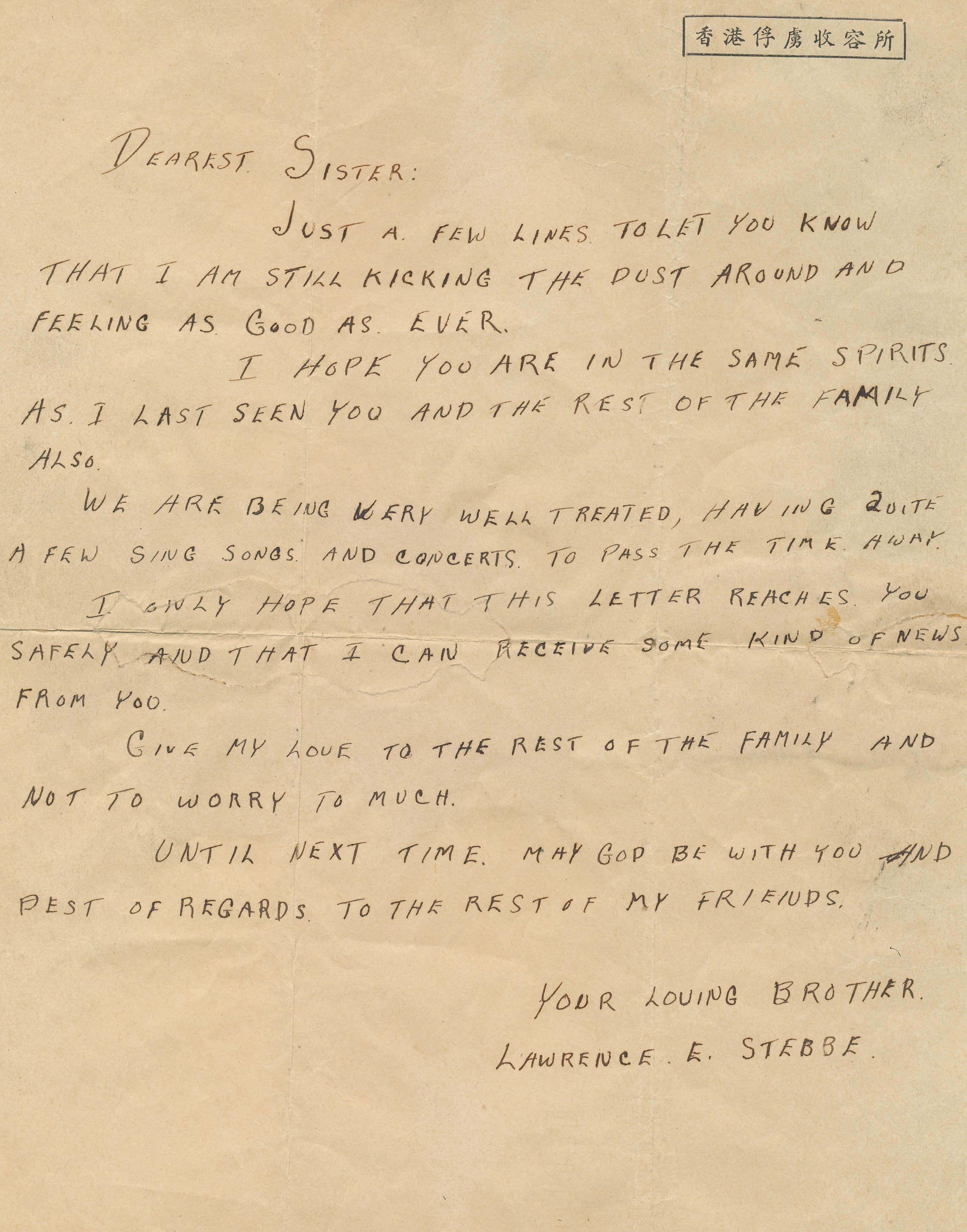

Veteran Story: Larry Edward Stebbe

“When we were first captured [after Allied positions were overrun on December 25, 1941], we went back to our barracks in Hong Kong and then a few months later, we were transferred over to a camp over on the island, North Point Camp. Food was the most important part which we never did have very much of, and then sickness, you start diarrhea, dysentery and big sores formed on your legs from malnutrition. And I still have scars all the way up my legs and stuff from malnutrition. Yeah, and, I don’t know, I guess some of the men they just gave up and died and that was it.”

Veteran Story: Jean-Paul "JP" Dallain

“[Being taken prisoner of war] is a bit like a sickness or an accident: you can’t foresee anything, you’re in the dark. You live one day at a time. The first year there, many fell ill and many died from dysentery.

“Eventually, the Japanese sent a first group of Canadian prisoners to Japan. ‘Things will be good there.’ It was worse. They were always referring to the emperor. There were a number of camps in Japan where Canadians were held captive. You often read that [the camp in] Niigata was the deadliest. But I’m not saying that the other camps were picnics, either.”

Liberation

In August 1945, almost four years after the fall of Hong Kong, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war in the Pacific. By this time, 264 Canadians had died as POWs, while 1,418 liberated survivors were returned to Canada — many of them deeply bitter at the cruelty of their Japanese captors.

The government in Ottawa appointed a royal commission to investigate Canada’s involvement in Hong Kong, but no blame was laid against the Cabinet or senior military commanders.

The Canadians who died in the battle and in POW camps are remembered in Hong Kong today by a memorial to all of the territory's defenders. Hundreds of the Canadian dead are buried at military cemeteries in Hong Kong and Japan.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom