“African North Americans”

“African North American” is a term used by historian and New York Times writer Adam Arenson to describe those of African descent who “crossed or re-crossed the United States–Canada border between 1850 and 1930." As early as the American Revolution, Black people had left the United States seeking security, freedom and equal opportunity in Canada. However, life in Canada was not without difficulties: although slavery was no longer legal in Canada after 1834, Black persons in Canada still suffered discrimination, oppression and poor employment prospects. Once the American Civil War began, many returned to the United States to enlist as soldiers in the Union army. Although many moved back to Canada after the war, others remained in the United States and were joined by large numbers of Black people from Canada who wanted reunion with their families and who believed there would be opportunities in a country newly committed to ending the practice of slavery. The result was a North American Black community that straddled the border, with many individuals travelling frequently between the two countries in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Researching Dr. Roman

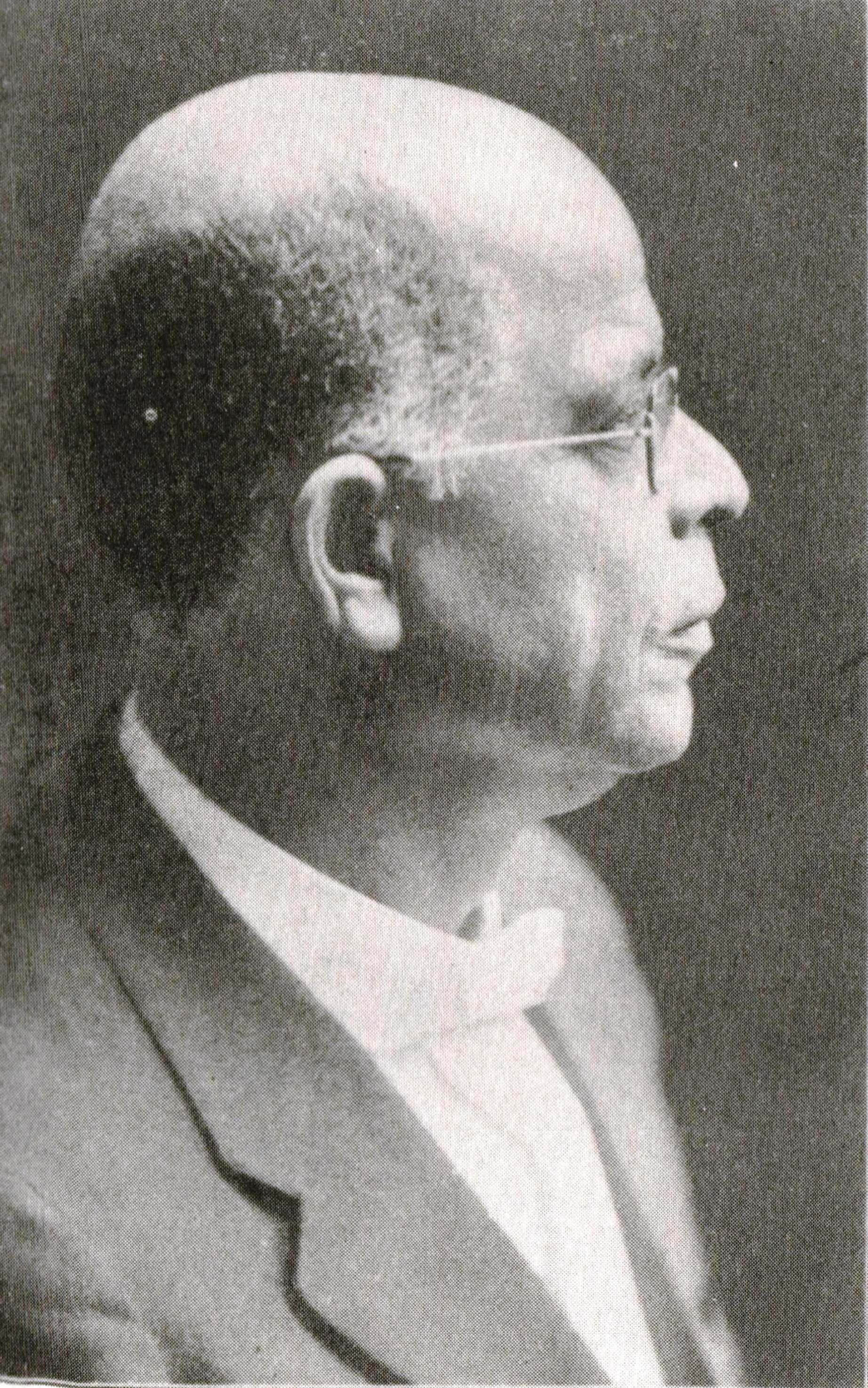

Dr. Roman was an internationally respected medical figure and a well-known author about whom much has been written in the

Family Background and the Underground Railway

Charles Victor Roman was the son of James William Roman, a fugitive slave who escaped from Maryland to Canada through the Underground Railroad. His mother, Anne Walker McGuinn, was the daughter of fugitive slaves Mary Anne and John Walker McGuinn, who had become landowners and successful farmers in Burford, ON.

Sometime before 1860, James and Anne Roman returned to the United States; the 1860 US census for Williamsport, Pennsylvania, lists James and Anne as well as their children (including Charles). The 1860 census also indicates that James captained a canal boat, which was probably owned by Anne (the census lists assets under her name). She likely purchased the boat with money from her father, John Walker McGuinn, who used the proceeds of his Burford, ON, farm to finance his children's endeavours in both Canada and the United States.

Records indicate that the Roman/McGuinn family not only used the Underground Railroad as fugitives, but also eventually became sponsors and agents of the famous escape route. Therefore, while James carried goods downriver to Chesapeake Bay, it is very likely that on the return trip, he had fugitive slaves holed up in the bilge of the craft. One of the most famous agents of the Underground Railroad, Daniel Hughes, operated his boating business in Williamsport and lived near the Romans.

Around 1870, the Roman family moved to Canada and settled on the family farm in Burford. The reason for the move is not clear. For six years they lived alongside Anne's parents and her brother. While farming was a means of support for the family, James also made and sold brooms, a skill he had learned back in Maryland, to augment the household income.

Early Life

Charles Roman, the fourth child of the family, was born in Williamsport; he was around six years old when the Romans moved to Burford. As a child living on the farm, he met a local root doctor who paid the boy a few pennies a day to help gather plant material and herbs. Charles became quite adept at his job. He was very attentive and was intrigued by the curative abilities of the root doctor, whom he saw as a mentor. A local Burford physician recognized him as an extremely bright and gifted child and remarked, “You’ll be a doctor some day.”

In 1876, the Cotton Company in Dundas, ON, was expanding its mill and advertising for workers, especially children, who could earn almost four dollars per week (a good wage at the time). Charles was then 12, the age a child could legally begin working at the mill. The mill therefore presented an employment possibility for Charles and for his father, who could potentially provide the mill and townspeople with a regular supply of brooms. Charles, his parents and his six siblings therefore moved to the town of Dundas, which was not far from Hamilton. Charles was hired straight away and began work at one of the machines. Days at the mill were long — from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Charles was at the mill by 5:30 a.m. for fear of being late. As he worked full days Monday to Friday as well as a half day on Saturday, he had no time to attend regular classes at school. He therefore learned from the town library and night school classes whenever time allowed (Reverend Featherstone Osler, father of Sir William Osler, had established a night school for the boys at the mill).

Workplace Injury

Work in the cotton mill was difficult and dangerous. The constant clatter and racket of machinery made it extremely difficult to hear and the long hours left workers exhausted. Some safety measures existed but these were inadequate and accidents were many. The resulting injuries too often resulted in loss of limbs or even death. At age 17, Charles fell victim to a lapse in concentration or a mechanical malfunction — his leg was badly mangled by a machine and had to be amputated.

Education

The disability forced young Charles Roman to give up his job and left the teenager with few opportunities to earn a decent living. Long eager to gain an education, he enrolled in the local high school. Despite his lack of formal schooling, Roman completed the four-year program at Hamilton Collegiate Institute after only two years of study.

Following graduation, Roman was dismayed to learn that being Black and disabled meant work was scarce. He made what money he could by selling notions (sewing items such as thread, ribbon and buttons) on the street, hoping to save enough to go to medical school. In the evening, he would attend presentations by travelling lecturers. In 1885, one of those lecturers learned of Charles’s high school education and encouraged him to apply his education and earn a better income teaching school in southern states such as Tennessee and Kentucky.

Charles relocated and accepted a position as a public school teacher in Trigg County, Kentucky. He later moved from there to Nashville, Tennessee, where he continued teaching, intent on putting aside the necessary funds to return to Canada and begin studies to become a doctor.

Medical Career and Practice

In 1886–87, Roman was teaching in Columbia, Tennessee, and boarding with Dr. John Halfacre, who was a graduate of Meharry Medical College in Nashville. When Roman told Halfacre that he was trying to save enough money to eventually return to Canada and study medicine at McGill University, the doctor suggested that he continue teaching in Tennessee while simultaneously enrolling in classes at Meharry Medical College. Roman took his advice and graduated in 1890 as a physician, proudly opening his medical practice. A year later, Charles married Margaret Lee Voorhees of Columbia, Tennessee; he worked for the next two years in Clarksville.

From 1893 to 1904, Roman had a private practice in Dallas, Texas. In 1899, Roman took a brief hiatus to pursue studies at the Post-Graduate Medical School of Chicago. In 1904, he travelled across the Atlantic Ocean where he studied as an ophthalmologist at the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital and as an otolaryngologist at the Central London Nose, Throat, and Ear Hospital.

In 1904, Roman returned to his alma mater,

Roman was offered honorary masters degrees but was determined to actually fulfill the requirements. Therefore, while working as a professor at Meharry, he earned a Master of Arts in history and philosophy in 1913 from nearby Fisk University in Nashville. Three years later, he published his first major work, American Civilization and the Negro.

Roman eventually became head of the Department of Health at nearby

In addition to his professorial, lecturing and surgical work, Charles was the fifth president (1904–5) of the National Medical Association (NMA) and edited the organization's Journal of the National Medical Association from 1909 until 1919. He also served as a medical lecturer for the United States Army during the First World War, speaking primarily to African American soldiers on the topic of sex hygiene (sex hygiene dominated many medical lectures for soldiers during the First World War).

Author and Activist

Following the First World War, Dr. Roman was associate editor of the National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race in 1919. He shared his time and talents as a member of several prominent organizations, including the American Academy of Political and Social Science, the Southern Sociological Congress, the Knights of Pythias (an international, non-sectarian organization dedicated to peace), and the Odd Fellows (one of the oldest and largest service-oriented organizations in the world). He was also a lay leader of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Roman also wrote several books and almost 60 articles (see list of publications below). In 1913, he delivered an address titled "Racial Self-Respect and Racial Antagonism" to the Southern Sociological Congress in Atlanta. This speech earned Dr. Roman accolades in a number of publications that focused on race relations, such as the Crisis and the Journal of the National Medical Association. A common theme in his many speeches and writings was encouraging African Americans to use their resources to bolster Black businesses, organisations and institutions. In an effort to defuse racial prejudice, Roman emphasized the benefits reaped by American society because of the contributions made by Black people.

Family Ties

While Roman and his wife had no children, they took a particular interest in his nephew, Charles Lightfoot Roman, using their resources and connections to mentor him and help finance his medical education at McGill University — the school the elder doctor had himself hoped to attend had times and circumstances been different.

As a medical student, Charles Lightfoot Roman travelled overseas during the First World War with the Canadian Expeditionary Force and served in France for a number of years as a member of McGill University's Number Three Hospital. Lightfoot Roman graduated as a doctor in 1919. He was so affected by the stories his uncle shared with him about his tragic childhood experience working in the cotton mill that he became one of Canada's first industrial doctors, establishing a medical practice that served the employees of the Montreal Cottons textile mill in Valleyfield. His wife, Jessie Middleton Sedgwick Roman, a registered nurse, worked alongside him.

Legacy

Dr. Charles Victor Roman died on 25 August 1934 and was buried at Greenville Cemetery in Nashville, Tennessee. He left a legacy of distinction. Despite the trauma of losing his leg at age 17, Roman went on to become the first Black person to graduate from high school in Hamilton, ON, completing the four-year programme in only two.

Roman was the first African North American physician to receive training in both ophthalmology and otolaryngology. He laid a path to the entrance of Meharry Medical College and to Fisk University that other Black Canadians followed. Roman argued that Black people deserved the opportunity to further their education and was himself cited as the case in point for Black intellect and possibility.

Roman’s success helped to destroy contemporary theories about Black intelligence. In the early 1900s, anthropologists such as Robert Bennett Bean (in the American Journal of Anatomy, 1906) argued that Black people possessed inferior intelligence. Similar theories appeared in reference books such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica; for example, the 11th edition (1911) stated that “the mental inferiority of the negro to the white or yellow races is a fact.” Roman shattered this stereotype. His exemplary academic achievements and medical expertise were widely respected and heralded at Meharry Medical College, Fisk and Tennessee State Universities.

Roman’s influence can still be seen in the historical manifesto of the National Medical Association, an organization that today represents the interests of more than 30,000 African American physicians and the patients they serve. The manifesto was written in 1908 by Roman, one of the founding members of the organization:

Conceived in no spirit of racial exclusiveness, fostering no ethnic antagonism, but born of the exigencies of the American environment, the National Medical Association has for its object the banding together for mutual cooperation and helpfulness, the men and women of African descent who are legally and honorably engaged in the practice of the cognate professions of medicine, surgery, pharmacy and dentistry.

Publications

Books

A Knowledge of History Is Conducive to Racial Solidarity (1911)

Science and Christian Ethics (1913)

American Civilization and the Negro (1916)

Articles (selection)

“Therapeutics of Pulmonary Tuberculosis,” Journal of the National Medical Association 4, no. 1 (1912): 1–7.

“Racial Interdependence in Maintaining Public Health,” Journal of the National Medical Association 6, no. 3 (1914): 153–157.

“The Medical Phase of the South’s Ethnic Problem,” Journal of the National Medical Association 8, no. 3 (1916): 150–152.

“Fifty Years' Progress of the American Negro in Health and Sanitation,” Journal of the National Medical Association 9, no. 2 (1917): 61–67.

“Syllabus of Lecture to Colored Soldiers,” Journal of the National Medical Association 10, no. 3 (1918): 104–108.

“The Venereal Situation,” Journal of the National Medical Association 11, no. 2 (1919): 72–74.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom