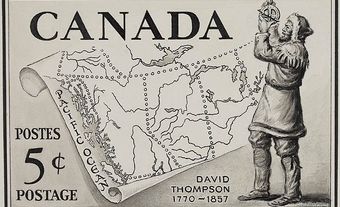

Charlotte Small Thompson, Cree wife of and collaborator with David Thompson (born ca. 1785 in or near Île-à-la-Crosse, SK; died 4 May 1857 near Montreal, QC). Charlotte’s husband, David, is celebrated today as one of North America’s most accomplished geographers. Between 1799 and Thompson’s retirement from the fur trade in 1812, Charlotte travelled with him more than 20,000 km across northwestern North America. She raised a growing family while doing so — 5 of her 13 children were born during this period — as well as provided linguistic, logistical and subsistence support for her husband’s fur trading and survey work with the North West Company. The couple lived the rest of their long lives in Eastern Canada, far from Charlotte’s Cree homeland.

Early Life

Charlotte Small Thompson’s mother, unnamed in records, was Cree. Her father was Patrick Small, a Scottish North West Company fur trader. Small had charge of the trade at Île-à-la-Crosse, in what would become Saskatchewan, from 1783 or 1784 until 1788, when he left for a year in Montreal. Returning in 1789, he left the fur trade for Scotland in 1791. At Île-à-la-Crosse, he had a son and two daughters, possibly by different women. Small never acknowledged the mother(s) as wives or maintained ongoing relations with them. His colleague William McGillivray and other traders knew Small as the children’s father, however, and preserved their paternal surname.

Charlotte grew up among her Cree maternal relatives with Cree as her first language. She met David Thompson around the age of 13, and he dated their marriage (as he regarded it) to 10 June 1799 at Île-à-la-Crosse. The union was evidently approved by her Cree relatives although David did not mention them in his writings. Other traders often allied themselves with Indigenous women, but David took his commitment more seriously than many. In his former service with the Hudson’s Bay Company (until 1797), he had already been learning Cree, the lingua franca of the fur trade. Now he had a fluent companion with her own networks of relatives among his closest Indigenous partners in trade and exploration.

The Fur Trade Years

Charlotte Small Thompson’s practical skills in trapping, processing pelts, making leather clothing, gathering wild foods and so on, were essential to David Thompson’s work and to the family’s survival. David never wrote much about her or her contributions. But at times he recorded how she snared rabbits both for food and to weave rabbit-skin blankets, and how she and other women gathered and processed spruce roots, essential for sewing and mending birch bark containers and canoes. One time, the women asked him for beads and ribbons, and David replied that he needed marten skins for his trading, and could they help? So the women headed out to set marten traps. That evening, to encourage a successful harvest, they danced “with the Rattle and tambour” to “the Manito of the Martens” — an occasion David always remembered.

Charlotte’s linguistic and cultural knowledge were invaluable. She and her relatives gave David a much deeper understanding of Cree ceremonies and customs than most other European traders acquired. He learned that her people called themselves “Nahathaway,” not “Krees” as was the French Canadian term for them. He found the language “soft and easy to learn and speak.” In about 1847, David observed that he had “lived several years with the Na Hath a way Indians….being present at their various ceremonies, living and travelling with them, and my lovely Wife is of the blood of these people, speaking their language, and well educated in the english language, which gives me a great advantage.”

Life After the Fur Trade

David Thompson’s attachment to Charlotte Small Thompson, enduring over 58 years, stood out among fur trade unions. So did his act of marrying Charlotte in church at the first opportunity, on 30 October 1812, soon after the couple arrived in Eastern Canada. Baptism came first; Charlotte and four of their children were baptized on 30 September.

The Thompsons lived 45 years after leaving the fur trade country. The remaining 8 of their 13 children were born during this period, in Lower or Upper Canada (later Quebec or Ontario). Three children died young, one in infancy and the other two at age five and seven. By the 1830s, years of economic depression, the Thompsons slipped into poverty. David’s survey work and land speculations could barely support his large family. He died on 10 February 1857, at the age of 86, just a few months before his 87th birthday. Charlotte died a few months later, on 4 May, at about the age of 72.

Few glimpses of Charlotte Small Thompson survive from her later life. In 1917, Joseph Burr Tyrrell, the first scholar to publish an edition of David Thompson’s writings, interviewed one of Charlotte’s grandsons, William Scott. Scott had lived with his grandparents for some years in his boyhood. He described Charlotte as “active and wiry” with black eyes and almost copper-coloured skin. She was gentle and kind, he said, and “an excellent housekeeper” who did not socialize outside her family. In 1928, Tyrrell summarized his conclusions about Charlotte: “Mrs. Thompson was a model housewife, scrupulously neat and devoted to [Thompson] as he was to her.” He imagined Charlotte as having made a transition from her culture to a Euro-Canadian one, and more specifically, to the role of a domesticated White wife tending to a household and family in accord with the Eastern Canadian norms of her time.

Identity

There is no record of how Charlotte Small Thompson and her husband viewed her identity and its possible evolution over the years. In recent decades, some writers have described her as Métis because she had a White father and an Indigenous mother. But to define her in terms of race or “mixed blood” overlooks the facts that she grew up Cree and that it was her Cree-ness that defined her major role as David Thompson’s wife and partner in the fur trade. David and his contemporaries never called her Métis. In their times, the term usually referred more narrowly to persons of Indigenous/French Canadian descent who began by the 1820s to emerge as a culturally and politically distinct group, particularly in the Red River region. Charlotte’s life path was unique and is worth following on its own terms, insofar as available evidence allows.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom