The Cold War refers to the period between the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. During this time, the world was largely divided into two ideological camps — the United States-led capitalist “West” and the Soviet-dominated communist “East.” Canada aligned with the West. Its government structure, politics, society and popular perspectives matched those in the US, Britain, and other democratic countries. The global US-Soviet struggle took many different forms and touched many areas. It never became “hot” through direct military confrontation between the two main antagonists.

Beginnings

The Cold War was rooted in the collapse of the American-British-Soviet alliance that defeated Germany and Japan in the Second World War. The Allies were already divided ideologically. They were deeply suspicious of the other side’s world plans. American and British diplomatic relations with Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union severely cooled after the war, over several issues. In particular, the Soviets placed and kept local communist parties in power as puppet governments in once-independent countries across Eastern Europe. This was done without due democratic process. This situation led former British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill to state on 5 March 1946 that an “iron curtain” had fallen across the European continent.

Gouzenko Affair

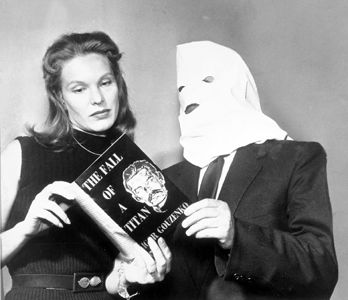

In February 1946, the Canadian government revealed that it had given political asylum to Igor Gouzenko. He was a Soviet cipher clerk stationed at the Soviet Union’s embassy in Ottawa. Just weeks after the end of the Second World War, Gouzenko left the embassy with documents that proved his country had been spying on its wartime allies: Canada, Britain and the United States. According to the documents, the Soviet embassy was home to several spies. They were connected to agents in Montreal, the United States and the United Kingdom who had been providing Moscow with classified information.

Did You Know?

English writer George Orwell first used the term Cold War in a 19 October 1945 essay entitled “You and the Atomic Bomb” in a British magazine. In it, he described what he predicted would be a nuclear stalemate between two or three superpowers, each of which possessed weapons that could wipe out millions of people in a few seconds.

On 16 April 1947, American financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch used the phrase Cold War to describe the relationship between the US and Soviet Union in a speech written for him by British journalist Herbert Bayard Swope. “Let us not be deceived,” he said, “we are today in the midst of a Cold War. Our enemies are to be found abroad and at home. Let us never forget this: Our unrest is the heart of their success.”

These revelations caused a potentially dangerous international crisis. Canadians targeted by Soviet espionage worked in sensitive positions. They were privy to diplomatic, scientific and military secrets. This included highly classified information concerning research on radar, code-breaking and the atomic bomb. Several historians and critics consider the Gouzenko affair, as it was known, to mark the beginning of the Cold War era. They also believe it set the stage for the “Red Scare” of the 1950s.

The Gouzenko affair led to widespread investigations in Canada, the US and Great Britain. In Canada, 39 suspects were arrested and 18 were convicted. Some of the most high-profile Canadians who were convicted included: Fred Rose, who was a member of Parliament; Sam Carr of the Labor-Progressive Party (see Communist Party of Canada); and Canadian Army Captain Gordon Lunan.

Cold War Deep Freeze

The period 1947 to 1953 became the Cold War’s “deep freeze.” East-West negotiations on the future of Europe broke down and stopped. The international climate worsened with several high-profile events. Canadians were involved in some of them, including the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a western security pact designed to defend Western Europe against Soviet invasion; and the Korean War (1950–53) in which Canadian forces fought with the United Nations against communist North Korean and Chinese forces supported by the Soviets.

NATO

In the late 1940s, Ottawa and other Western capitals watched with concern as the Soviet Union created a buffer zone in Eastern Europe — the “iron curtain” — between itself and the West. The Soviet Union imposed its will on East Germany, Poland and other central and southeastern European nations. The USSR pursued a policy of aggressive military expansion at home and subversion abroad. There was real fear that France, Italy or other nations might become communist and eventually ally themselves with the Soviets.

In response, Western allies formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949. At the core of the treaty was a security provision. It stated that “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.” NATO was Canada’s first peacetime military alliance. Signed on 4 April 1949, it included 11 other nations: the United States, Iceland, Britain, France, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal and Italy. Other European countries joined later in the Cold War: Greece and Turkey in 1952, West Germany in 1955 and Spain in 1982.

As a result of the formation of NATO, the Soviet Union established the Warsaw Pact on 14 May 1955, immediately following West Germany joining the western alliance. The Warsaw Pact was a collective defence treaty consisting of the Soviet Union and seven of its satellite states in Central and Eastern Europe: Albania (withdrew in 1968), Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Non-Aligned Movement

The year 1955 also saw the beginnings of what became known as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). At the Bandung Conference of Asian and African countries that year, attendees called for “abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve the particular interests of the big powers.” In particular, they believed that in the context of the Cold War, developing countries should abstain from allying with either of the two superpowers and instead band together in support of national self-determination.

The NAM was founded in 1961, under the initial leadership of India, Indonesia, Ghana, Egypt and Yugoslavia. As a condition of membership, NAM states could not be part of a multinational military alliance (such as NATO or the Warsaw Pact) or have a bilateral military agreement with one of the big powers if “deliberately concluded in the context of Great Power conflicts.”

Korean War

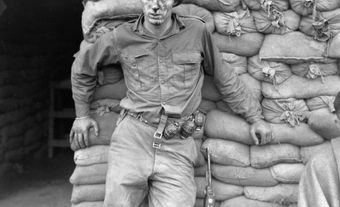

NATO existed largely as a paper alliance until the Korean War. It was the first major conflict of the Cold War. It led the NATO states — many of them fighting in Korea under the banner of the United Nations — to build up their military forces. For Canada, this resulted in a huge increase in the defence budget and, eventually, the return of troops to Europe. By the mid-1950s, about 10,000 Canadian troops were stationed in France and West Germany.

More than 26,000 Canadians served in Korea, during both the combat phase and as peacekeepers afterward. The last Canadian soldiers left Korea in 1957. After the two world wars, Korea remains Canada’s third-bloodiest overseas conflict. It took the lives of 516 Canadians and wounded more than 1,000.

Arctic Sovereignty

Amid fears of Soviet aggression, the United States heightened its military capabilities in the Arctic. This posed a potential threat to Canadian claims to the North. (See Canadian Arctic Sovereignty). The Department of Resources and Development, which oversaw Inuit affairs at the time, decided to populate Ellesmere and Cornwallis islands with Inuit, even though the areas were devoid of human population. In 1953 and 1955, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) moved approximately 92 Inuit from Northern Quebec and what is now Nunavut to settle two locations on these High Arctic islands. Trade and economics also played a role in the relocations. (See Inuit High Arctic Relocations.)

Did You Know?

Cold War tensions brought unprecedented attention to the Canadian North. The current version of the Canadian Rangers was established in 1947 to work in remote, isolated and coastal regions of Canada. Their mission is to support Canadian Armed Forces national security and public safety operations. In the decades that followed, the Rangers developed as a sub-component of the Canadian Army Reserve.”

Domestic Concerns

As the Gouzenko affair showed, the Cold War was felt as much at home as abroad. There were communist “witch hunts” in Canadian government and society. These were perhaps more subdued than the ones in the US, but they had real consequences. Communists were identified and purged from trade unions. LGBTQ individuals, who were considered susceptible to blackmail and coercion, were purged from the federal public service and the armed forces. (See Canada’s Cold War Purge of LGBTQ from Public Service and Canada’s Cold War Purge of LGBTQ from the Military.)

Canadian diplomats with allegedly questionable loyalties were put under suspicion. Tragically, Canadian ambassador to Egypt E. Herbert Norman committed suicide in Cairo in 1957. This came after almost a decade of various accusations and investigations by American intelligence agencies into his communist associations during the 1930s. Although he did have those associations, the Canadian government affirmed its confidence in him.

Canada and the Cold War

Serious East-West diplomatic discussions resumed after the death of Stalin in 1953. But international tensions remained high for the next several decades. On a global scale, Canada contributed armed forces to peacekeeping operations throughout the world; this included areas divided between communist and anti-communist factions. Canadian political and military leaders were at times critical of American actions against communism in the Middle East, Latin America and Asia; but they still prepared for possible war against the Soviets in Europe.

Did You Know?

By the 1950s, there was a growing concern that Soviet bombers would attack North America from the Canadian Arctic. In fact, NATO intelligence suggested that such an attack could occur as early as 1954. In response, in 1953–54, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) commissioned Avro to design and build the Arrow. It was an all-weather nuclear fighter jet meant to fly higher and faster than any aircraft in its class. (See Avro Arrow.)

Canadian Forces in Europe

The Canadian NATO commitment in Europe included an army brigade group in West Germany and air force fighter jets capable of carrying nuclear weapons in France and West Germany. This marked the first time during peace that Canada had stationed armed forces abroad. Canada’s contributions included 4 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group, which was stationed in Germany during the Cold War. It also committed infantry battalion groups to Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land). The units were stationed in Canada but could be deployed quickly to Europe if necessary. Canada also contributed air power to NATO. It formed 1 Air Division (1 AD) in 1951 as the country’s air contribution to NATO in Europe. This eventually became 1 Canadian Air Group.

Under the government of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Canada reduced the size of its land and air forces stationed in Europe. In response to allied criticism, the Canadian government created the Canadian Air-Sea Transportable (CAST) Brigade Group in 1968. This new formation was stationed in Canada but could deploy to Norway in times of tension on 30 days notice from the Norwegian government.

Did You Know?

Before 1970, when the regulations changed, Canadian service personnel and their dependants who died while stationed in Germany and France were buried there, in local civilian cemeteries. Almost 1,400 Canadians are buried in the two countries, with 474 in Werl alone.

For Canada’s government and its people, the fear of nuclear war remained ever-present throughout the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Canadians were active at various levels in trying to avoid such a calamity.

“MAD”

For much of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union held each other to a nuclear standoff known by its acronym, MAD, for mutual assured destruction. The theory behind MAD — thankfully never put to a practical test — was that even after an initial surprise nuclear attack by one side, the other side would still retain enough of a second-strike capability to retaliate in kind. It was thought such a capability would act as a deterrent to both sides. If ever employed, the net result of mutual assured destruction would likely have been the end of civilization.

NORAD

In the early 1950s, defence agreements between Canada and the US centred on the construction of early warning radar networks across Canada to detect Soviet manned bombers carrying nuclear weapons. This eventually resulted in three lines of radar stations: the Pine Tree Line, the Mid-Canada Line and the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line. Such cooperation led to talks about the possible integration of air defence arrangements.

On 1 August 1957, the Canadian and American governments announced they would integrate their air-defence forces under a joint command called the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD). At this stage in the Cold War, both Canada and the US feared long-range Soviet attack. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and the United States Air Force (USAF) would work together to ensure protection.

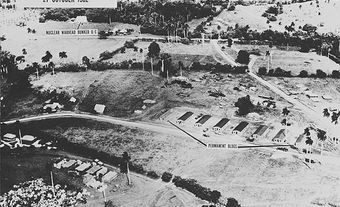

Did You Know?

The “Diefenbunker” is an underground bunker designed to withstand the force of a nuclear blast. It was built between 1959 and 1961 in Carp, Ontario, during a peak in Cold War tensions. It was named after then-Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. It is now the location of Canada’s Cold War Museum. (See Diefenbunker, Canada’s Cold War Museum.) Similar bunkers were built at the provincial level.

Bomarc Missile Crisis

In late 1958, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s Conservative government announced an agreement with the US to deploy American “Bomarc” antiaircraft missiles in Canada. This controversial defence decision was one of many flowing from the 1957 NORAD agreement.

Some argued that the missiles would be an effective replacement for the Avro Arrow, which the Diefenbaker government scrapped in early 1959. The missiles would theoretically intercept any Soviet attacks on North America before they reached Canada’s industrial heartland. (See Civil Defence.)

However, the government did not make it clear that the missiles would be fitted with nuclear warheads. When this came to light in 1960, a dispute erupted as to whether Canada should adopt nuclear weapons. In the end, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson decided to accept the nuclear warheads in 1963. (See Bomarc Missile Crisis.)

Cuban Missile Crisis

On 15 October 1962, an American spy plane discovered that Soviet missiles were being installed in Cuba. This was seen as a direct threat to the United States and Canada. Canadian forces were placed on heightened alert during the crisis that followed. But Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s hesitant response aggravated US President John F. Kennedy; it fuelled already difficult relations between Canada and the US in the 1960s. The crisis brought the world to the edge of nuclear war. It ended on 28 October 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev agreed to dismantle and remove the Soviet missiles in return for Kennedy’s promise not to invade Cuba. (See Cuban Missile Crisis.)

The Cold War at Sea

During the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) became a recognized expert in antisubmarine warfare (ASW). This continued as its main role in the Cold War. In conjunction with NATO navies, the RCN patrolled and monitored the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans for Soviet submarines. Canada designed and built 20 world-class destroyer escorts specifically for ASW, cooperated with the US in monitoring a system of underwater sensors to detect submarine activity, pioneered the use of shipborne ASW helicopters and replaced its fleet of ASW fixed-wing aircraft (see Tracker and Argus).

In January 1968, NATO established the Standing Naval Force Atlantic (STANAVFORLANT, abbreviated to SNFL and pronounced “sniffle” by sailors) as a permanent maritime quick reaction force. SNFL was designed to respond rapidly to a crisis and establish a NATO presence and resolve. The force consists of six to 10 destroyers, frigates and tankers attached for up to six months. Canada is one of five permanent contributors. During the Cold War, SNFL was normally positioned off the northwest coast of Europe and tasked to defend the North Atlantic. RCN commodores and rear admirals commanded SNFL on a rotational basis. (See also Canada and Antisubmarine Warfare during the Cold War.)

Fall of the Soviet Union

The Cold War began winding down in the late 1980s amid new efforts at openness by the Soviet leadership and a surge of freedom movements inside the European communist states. Between the summers of 1989 and 1990, democratically elected governments replaced all the former communist regimes in Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria. Among the most visible signals of the collapse of communism were the tearing down of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 (which had separated West and East Germany since 1961) and the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom