Key Terms

Labour: Generally, labour means work. But in this article, it stands for workers (especially manual labourers) as a class or politica power.

Labour union: A group of workers that forms to protect its members’ rights and to seek better pay, benefits and conditions. The term is often shortened to union. (See Labour Organization.)

Early Life and Family

Little is known about James Ryan’s childhood and youth in Ireland. He married Margaret (Mary) Blake and together they had five children (Mary, Annie, James, Agnes and Thomas). The family settled in Hamilton, Ontario shortly before the Nine Hour Movement began in early 1872. (See also Irish Canadians.)

Nine Hour Movement

James Ryan played an important role in the Nine Hour Movement from January to June 1872. The goal of the movement was to reduce working hours from ten or more hours to nine hours per day. In Canada, the campaign began at a meeting at the Mechanics’ Institute in Hamilton on 27 January 1872.

Ryan stood on the platform of the meeting alongside presidents of trade unions, employers and a clergyman. He spoke second, explaining the goals of the Nine Hour Movement. He emphasized the benefits of having more time away from work: to “increase our mental power,” “to study and learn” and “to cultivate social and domestic virtues.” Ryan argued that the goal of the movement was self-improvement for workers: “We want not more money, but more brains; not to be richer serfs, but better men.” The recent acceptance of the shorter workday in Britain was, according to him, a reason for Canada to adopt the nine-hour day. He said: “What is right there, cannot be wrong here.” Ryan reassured employers in the audience that the workers did not want conflict, strikes or a lockout, but rather fair negotiation. He closed his speech by urging employers and employees to cooperate: “Let mutual esteem and respect between employers and employed continue.”

An announcement in the Hamilton Spectator about the Nine Hour Movement meeting at the Mechanics’ Institute in Hamilton, Ontario, on 27 January 1872.

Secretary of the Nine Hour League of Hamilton

In the days following the meeting at the Mechanics’ Institute, the Nine Hour League of Hamilton was formed. James Ryan became its secretary. He represented the movement with speeches, writings and participation in meetings in various cities. One of its goals was to unite workers in Nine Hour leagues across Ontario and into Quebec as a way to build power and influence for the movement. Hamilton employers, concerned about keeping their competitive edge, were more likely to embrace the nine-hour workday if it caught on in other cities.

Throughout the early months of 1872, Ryan was busy delivering speeches to grow the movement. He also wrote to workers in Ontario and Quebec to gain support for what he called “a social revolution.” Ryan spoke at meetings across Ontario, including Dundas, Oshawa and Ingersoll. In March 1872, he travelled to Montreal to coordinate the efforts of labour groups in Montreal, Toronto and Hamilton into a single plan. In particular, Ryan worked on agreements with labour in the two larger cities to provide financial support to workers in Hamilton if they were forced to strike.

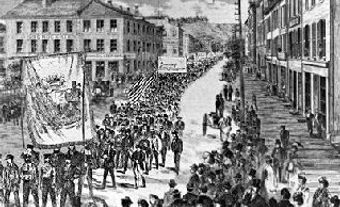

On 15 May 1872, Ryan was part of a group of up to 3,000 workers who walked through the streets of Hamilton in peaceful protest for the nine-hour day, effectively creating a city-wide strike. Even though most Great Western Railway workers (including Ryan) had obtained the nine-hour day the month before, he and other railway workers marched in solidarity.

Did you know?

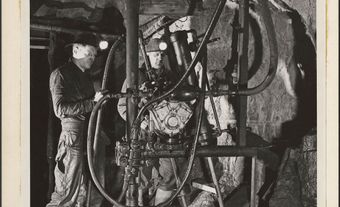

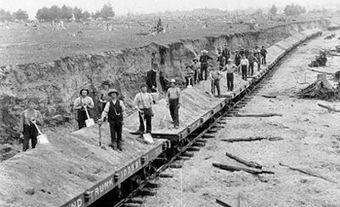

The Nine Hour Movement in Canada was largely led by railway workers, including the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners. At the time, the railways were the largest employers in Canada. The Great Western Railway alone employed approximately 20 per cent of all male industrial workers in Hamilton in 1872. (See also Railway History.)

Later Life

The Nine Hour Movement did not achieve its goals on a broad scale. However, it united workers around a central cause and helped create the Canadian labour movement.

Little is known about James Ryan’s life after his leadership in the Nine Hour Movement. His last known public speech was in early June 1872 at a mass meeting for the Nine Hour Movement. That meeting drew a much smaller number of supporters (300) than earlier events. Ryan was notably absent from subsequent labour protests and events, including the formation of the Canadian Labor Union in 1873. The reason for his absence from the labour movement after June 1872 is unclear. However, Ryan continued working for the railway.

The Great Western Railway relocated its shops to London in 1874, putting many people out of work. In 1882, the Grand Trunk Railway took over the Great Western. It was at the Grand Trunk that Ryan later found work as a track labourer. He died at the age of 56 in 1896.

Importance

James Ryan was a prominent and impassioned voice in the Nine Hour Movement. He helped establish the Canadian Labor Protective and Mutual Improvement Association, from which grew the first national organization of unions, the Canadian Labor Union. Ryan’s labour activism, speeches and writing contributed significantly to the early history of the Canadian labour movement. (See also Working-Class History: English Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom