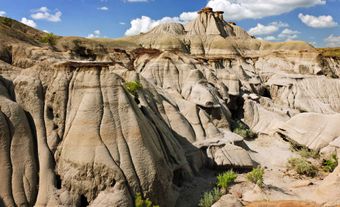

In the Prairies, the names of rivers and trading posts bear the mark of explorers and voyagers who travelled the region during the 18th and 19th centuries. Agriculture and the petroleum industry attracted many migrants from Quebec, Acadia, Ontario and neighbouring provinces, but also from New-England, France and Belgium. In 2016, 418,000 Albertans (10.5 per cent of the population) were of French or French-Canadian origins (see: Francophone; Alberta; History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies).

Voyagers, clerics and colonizers in the North-West

The fur trade owes its expansion to voyagers working for the Hudson’s Bay Company (1670) and the North West Company (1779) (see Fur Industry). Established in 1795, Fort Edmonton was initially a post where the main spoken language was French. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate went to the Prairies to evangelize the Indigenous peoples. The clerics founded the first towns where French-Canadian colonizers later settled.

When the British colonies from united Canada (Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick joined forces to form the Confederation in 1867, French Catholics were already present in the Albertan towns of Calgary, Lac Saint-Anne, Edmonton, Lac La Biche and Saint-Albert.

In 1869, Canada acquired the vast territory of Rupert’s Land. The goal was to establish a Euro-Canadian population there and for the country to be bordered by three oceans. A North-West Territories government was thus formed to enable the settlement. Although French and English were the official languages of the territorial legislative assembly, the arrival of anglophone colonists relegated the French language to a secondary status. In 1892, the government of the Territories declared English the only language to be used in the legislative assembly and in schooling.

The colonizing clerics actively recruited workers in New-England and farmers in Quebec to move to the Prairies and harvest the rich soils. The establishment of new towns gave rise to French-speaking schools and parishes. In 1894, the Grey Nuns opened a hospital in Edmonton.

In the form of social clubs and theatres, a new French cultural life emerged in the Edmonton region. Sections of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste (1894) and the Association catholique de la jeunesse canadienne-française (1913) were established. A few French-language newspapers were published, but they were short-lived.

The modest presence of French-language education

In 1905, when the province of Alberta was created without a mention of linguistic rights, French-language education was limited to the first two years of primary school. In other grades of primary school, French could be taught one hour each day. The French-Canadian clergy and elite attempted to influence the situation by getting involved in the Catholic school boards.

Originally created for training clerics, the Juniorat Saint-Jean, founded in 1908 by the Oblates, later became an educational institution for members of the local elite. At first, education in the Juniorat was conducted in the two languages, then, since 1928, in French only. In 1941 the institution was renamed the Collège Saint-Jean and later became affiliated with the University of Alberta.

The establishment of ten or so new francophone villages, namely in the region of Grande Prairie, stimulated the creation of new Catholic schools. To mobilize the parents and encourage them to demand concessions from the provincial government, the Franco-Albertans formed the Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta (1925), the Association des éducateurs bilingues de l’Alberta (1926) and the newspaper La Survivance (1928). They recruited French-Canadian teachers and distributed French-language textbooks.

A regulation created in 1926 and revised in 1936 formalized French-language primary education in 95 schools.

In 1944, the School Act was amended to allow for French to be taught for one hour per day up to Grade 9.

The rise of Franco-Albertan institutions

Le clerical and professional elites also concentrated on other forms of institutional development, namely the creation of tens of agricultural cooperatives and caisses populaires.

In the 1930s, plans to create a French-language radio station came to light. CHFA went on air for the first time on 20 November 1949 and became Radio Canada’s regional station in 1974.

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, new Franco-Catholic parishes were created.

However, some initiatives failed. Several caisses populaires shut down because of a lack of membership and two French-language bookstores went out of business after a few years.

The establishment of a Franco-Albertan school system

In 1968, following the creation of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, schools were allowed to teach in French during half of the school day, from Grade 3 to Grade 12. Bilingual schools became accessible to everyone, and not only to French Canadians. Unlike in other provinces, there was no difference between French immersion schools and French-language schools.

In 1970, as part of the Official Languages in Education Program, the federal government financially supported education in the minority language by offering an additional funding which totalled approximately 10 per cent of the regular costs.

In 1976, the Regulation 250/76 authorized schools to teach in French during 80 per cent of the school day. French Canadian parents were divided on the topic of homogeneous schools, which complicated matters for the Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta and its advocacy work.

The enactment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 prompted Franco-Albertan parents to approach Edmonton’s public and Catholic school boards and request the establishment of l’École Georges et Julia Bugnet, a fully francophone school. Their proposal was rejected because such an institution would surpass the time limit imposed on education in French. The school was still opened as a private establishment in 1983, but it closed down after its first year for a lack of public funding.

The Association de l’École Georges et Julia Bugnet initiated a prosecution following the Court Challenges Program in order to demonstrate the incongruence between the School Act and Section 23 of the Charter. The Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta ruled that the Charter allowed members of the minority to have a certain degree of control and management of their education system and institutions. The provincial court of appeal ruled that the number of right-holders in Edmonton justified the existence of a homogeneous French-language school, but Section 23 did not define the thresholds.

Given the confusion, the Supreme Court of Canada accepted to hear the case. The ruling issued on 15 March 1990 highlighted the “remedial nature” of Section 23 and underlined that French-language schools are essential for both the official languages and the cultures represented by those languages to flourish. The expression “minority language education facilities” indeed implied that the schools belonged to the language minority group, but judge Brian Dickson determined that this only guaranteed it a “degree of management and control”. It seemed that the threshold had been reached. However, it was not before 1993, when a second case came to light about Franco-Manitoban schools, that every province was mandated to create French-language school boards.

The following year, Alberta launched three regional school boards (dedicated to the North-West, Central and Southern regions respectively) with a collective starting federal budget of $24 million. Like in Ontario, the existence of Catholic and public schools gave rise to two mixed school boards and one Catholic school board (in Edmonton). However, there was no consensus on the relation between language and religion, and this disagreement led to relentless struggles. Some fought to open public French-language primary schools (namely in Edmonton in 1997) and others battled to split the Calgary mixed school board into one Catholic and one public school board in 2003.

Limited room for French in the provincial State

In 1988, as a reaction to the Supreme Court’s Mercure case, Alberta passed the Alberta Languages Act, making English the province’s official language and repealing the language rights enjoyed under the North-West Territories Act. However, the Act allowed the use of French in the Legislative Assembly and in court.

This new restriction on French was countered sparingly. In 1995, Alberta created a French-language service system for cases of criminal prosecution.

In 1999, the government instituted the Francophone Secretariat and joined the Ministerial Conference on the Canadian Francophonie. In 2017, the government established a first French Policy adopted the Franco-Albertan flag as the official emblem of the Franco-Albertan community. In 2018, the government declared March the Alberta Francophonie Month.

Alberta has four officially bilingual municipalities: Beaumont, Legal, Falher and Plamondon. Together with Morinville, Saint-Albert, Saint-Paul, Bonnyville and Smoky River, they make the Alberta Bilingual Municipalities Association.

Albertan Francophonie today

In 2016, French was the mother tongue of 86,705 Albertans (2 per cent of the population, while 10.5 per cent of Albertans were of French or French-Canadian origin) and 7 per cent of the population spoke French.

The Franco-Albertan community is largely made up of migrants: only 25 per cent of Franco-Albertans were born in Alberta, while 50 per cent were born in another province and 25 per cent are from abroad.

There are 20 French-language daycare centres and 42 French-language schools (with 8403 registered students) spread across 27 parts of the province. The Saint-Jean campus of the University of Alberta has 849 students and offers two college programs and nine university programs.

From 2006 to 2016, there was a 19 per cent rise in the number of Albertans who could express themselves in both official languages (from 225,000 to 269,000).

Since 1996, enrolment in French-language schools has increased by 260 per cent.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom