The province of Ontario has a majority Progressive Conservative government, formed on 2 June 2022. The premier of the province is Doug Ford and the lieutenant-governor is Edith Dumont. Its first premier, John Sandfield Macdonald, began his term in 1867, after the province joined Confederation. Between the start of European colonization and Confederation, the southern portion of what is now Ontario was controlled first by the French and then by the British, while much of the northern part was controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Ontario (Upper Canada) received representative government in 1791, from which time the colony was governed by a House of Assembly, a lieutenant-governor, and executive and legislative councils. In 1848, Ontario (Canada West) received responsible government. From this point the colony was governed by a House of Assembly, premier, and executive and legislative councils.

Provincial Government Structure

There are 124 seats in Ontario’s provincial government. Each seat is held by a Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) elected by eligible voters in their electoral district. According to the Elections Act, provincial elections are to be held on the first Thursday of June, every four years. Sometimes, should the party in power see it as advantageous, an election may be called before this date. Elections may also occur before four years have passed in cases where the government no longer has the confidence of the Legislative Assembly (see Minority Government).

As with the other provinces, Ontario uses a first past the post electoral system, meaning the candidate with the most votes in each electoral district wins. Typically, the party with the most seats forms the government, and the leader of this party becomes premier. However, a party with fewer seats may also form a coalition with members of another party or parties in order to form the government.

Technically, as the Queen’s representative, the lieutenant-governor holds the highest provincial office, though in reality this role is largely symbolic. (See also Ontario Premiers: Table; Ontario Lieutenant-Governors: Table.)

The premier typically appoints members of the Cabinet from among the MPPs belonging to the party in power. Cabinet members are referred to as ministers and oversee specific portfolios. Typical portfolios include finance, health and education.

History

Province of Quebec: 1763─91

The southern portion of what is now Ontario was originally part of a French colony called Canada (see New France). The northern portion was a part of Rupert’s Land, an area controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company. In 1763, following the Seven Years’ War, Britain took control of Canada as well as several other French colonies (see Treaty of Paris 1763). Through the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British established the Province of Quebec. At the time, this included the region around the St. Lawrence River and the southeastern corner of what is now Ontario. Over time, however, the new British colony grew to include what is now southern Ontario north to the area around Lake Superior. The Province of Quebec was administered by a governor and council, both appointed by Britain. The council was dominated by English-speaking Protestants.

Upper Canada: 1791─1841

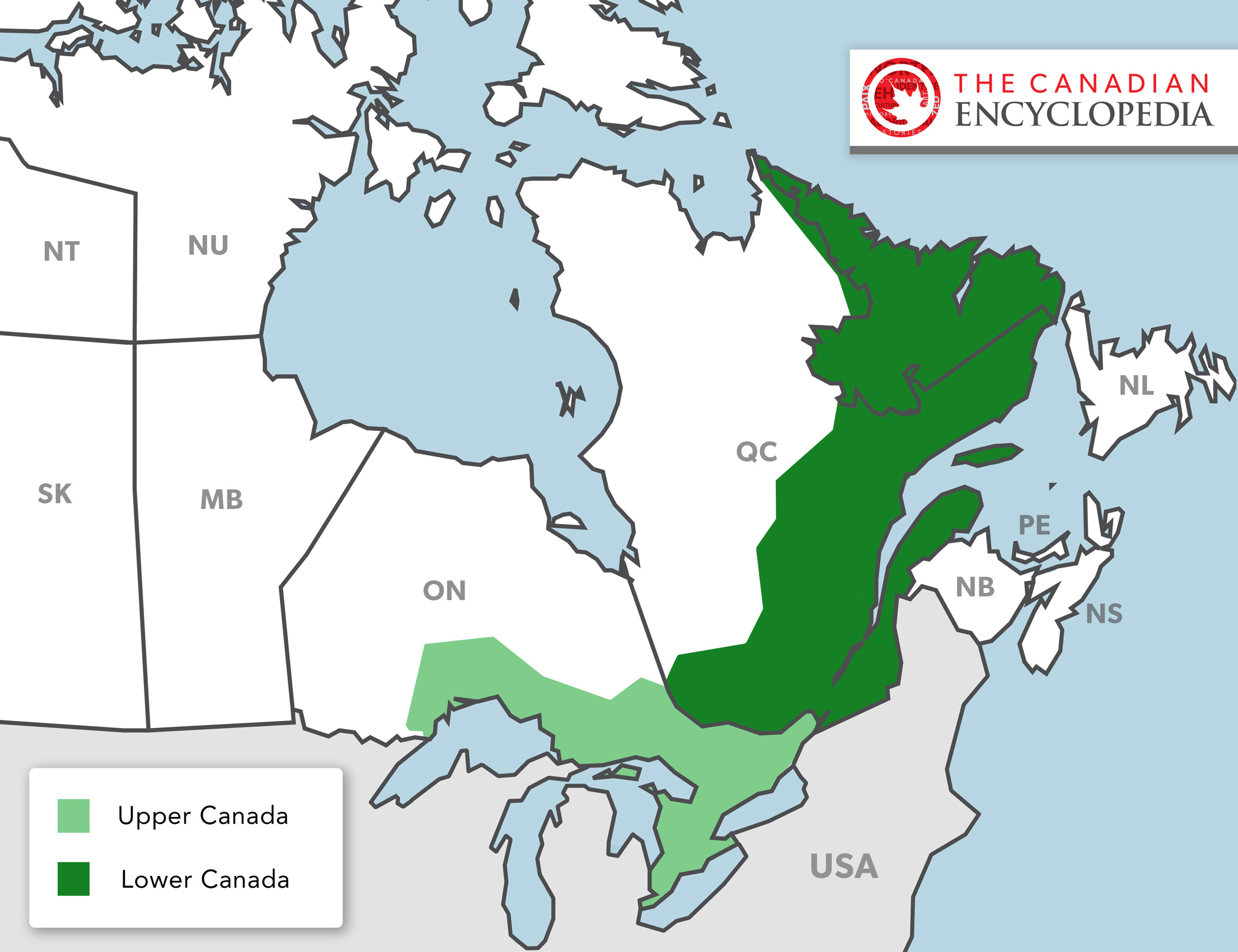

In 1791, Britain divided the Province of Quebec into two colonies: Upper Canada and Lower Canada. Upper Canada consisted of part of what would become Ontario, and Lower Canada part of what would become Quebec (see Constitutional Act 1791). The division was prompted by the arrival of thousands of Loyalists who sought refuge following the American Revolution. They pressed for British institutions and English common law. In response to this pressure, the Province of Quebec was divided along ethnic lines, with Lower Canada being predominantly French and Upper Canada being predominantly English.

In addition, the Loyalists lobbied Britain for representative government. As a result, in 1791, Britain granted representative government to both Upper and Lower Canada. In a representative government, members of a House of Assembly were elected by some residents of the colony (namely men who owned property of a certain value). However, the lieutenant-governor (or governor in Lower Canada), his executive council and a legislative council were all still appointed by Britain.

During this time, the Family Compact dominated politics in Upper Canada. This was a group of wealthy, conservative men, many of whom were appointed to the government’s unelected councils. They aimed to recreate Britain’s aristocratic society in Upper Canada, and were therefore wary of any suggestion of responsible government. Opposition to the Family Compact’s rule led to the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837. The rebellions in turn led to the Durham Report, which recommended that the two colonies be combined into one.

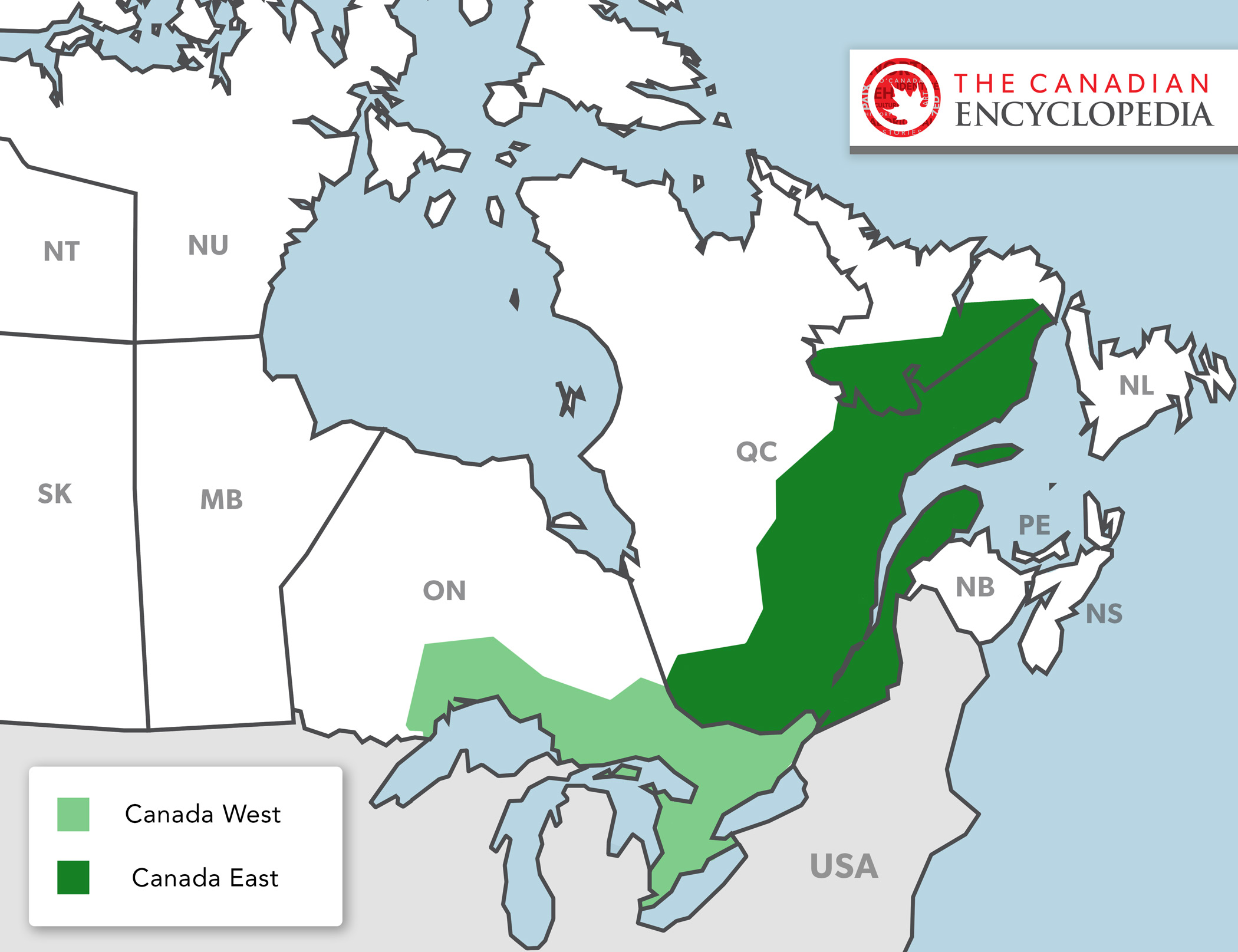

Canada West: 1841─67

In 1841, Britain combined Upper and Lower Canada into a single colony called the Province of Canada. Upper Canada became known as Canada West and Lower Canada as Canada East. Each region had an equal number of seats in the assembly, despite Canada East having a larger population. This gave English-speaking Canada West a political advantage over French-speaking Canada East. By 1851, however, the census showed that Canada West’s population had grown to exceed Canada East’s. Given this new advantage, politicians in Canada West, such as George Brown, began advocating for representation by population. Regardless, real power continued to be held by the colony’s appointed governor and executive and legislative councils.

In 1848, a political reform movement led to Britain granting responsible government to the Province of Canada. This meant that the premier and their executive would be selected from the party with the most members elected to the House of Assembly. In addition, the executive would need the support of the majority of the assembly in order to govern.

Did you know? Between 1791 and 1867, Upper Canada/Canada West had a legislative council, or upper house. Members of the legislative council were appointed by the lieutenant-governor until 1856, when the Province of Canada passed an act to have them elected. When Ontario joined Confederation in 1867 the legislative council was abolished; however, several other provinces (namely Manitoba, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Quebec) continued to include an upper house in their governments beyond 1867.

Confederation and Early Governments: 1867─1905

When tension between the English in Canada West and the French in Canada East made the Province of Canada difficult to govern, Confederation was proposed as a way forward. Ontario (formerly Upper Canada) was among the first provinces to join Confederation in 1867 (see also Ontario and Confederation).

Ontario’s first premier was John Sandfield Macdonald. Macdonald’s political affiliations shifted over the course of his career; however, at the time of his premiership he was aligned with Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives. When Edward Blake, a Liberal, won the 1871 election it was the beginning of 34 years of Liberal rule in the province. In 1872, Sir Oliver Mowat’s Liberal government succeeded Blake’s. Mowat advocated for the rights of the province in the face of the overriding powers of the federal government under Sir John A. Macdonald. He went on to win six general elections, in 1875, 1879, 1883, 1886, 1890 and 1894. When he left provincial politics in 1896, he had governed Ontario for 24 years, making him the province’s longest-serving premier.

The Liberal regime gradually declined beginning in the late 1890s under the leadership of Arthur Hardy (1896─99) and George Ross (1899─1905). In the 1902 election, the Liberal Party engaged in patronage, and won the election with a small majority. Shortly after the election, the Liberals were accused of bribery. Although found innocent, the party was defeated in the 1905 election.

Whitney, Hearst and Drury: 1905─23

The Conservative government under Sir James Whitney (1905–14) made its mark by establishing the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. In 1919, Whitney’s successor, Sir William Hearst, was defeated by the United Farmers of Ontario. Led by Ernest Charles Drury, the United Farmers of Ontario successfully implemented some of the legislation prepared by the previous government. For example, they put into effect a minimum wage for women, increased funding for education and better health services. However, the party was politically accident-prone. In 1923, they fell victim to a revitalized Conservative Party under Howard Ferguson.

Did you know?

In April 1917, women received the right to vote in Ontario elections. Ontario was the fifth province to grant women the vote (see Women’s Suffrage in Ontario). Today, anyone can vote in an Ontario election, as long as they are 18 years of age, a Canadian citizen and a resident of the province.

Ferguson and Henry: 1923─34

Conservative Premier Howard Ferguson was a determined man, as well as an able and wily politician. He created the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, which was designed to promote temperance as well as generate money for the provincial government. He also defused a long-standing controversy with the province’s French-language population by reintroducing official French classes in schools. In keeping with the premiers who came before him, Ferguson continued to develop provincial resources, including those in Northern Ontario.

George Henry succeeded Ferguson in 1930. Henry had to deal with the difficulties of the Great Depression, as well as attacks from a reinvigorated provincial Liberal Party under Mitchell Hepburn.

Hepburn, Conant and Nixon: 1934─43

In 1934, Mitchell Hepburn and the Liberals won the election with promises of reform and a revitalized economy. Neither goal was really achieved, although Hepburn did succeed in legislating the pasteurization of Ontario’s milk despite opposition from dairy farmers.

During the 1937 Oshawa Strike, Hepburn fought against the unionization of Oshawa’s General Motors plant. While both union organizers and Hepburn claimed victory, in 1937, Hepburn used the issue to fuel his re-election. His regime is also remembered for Hepburn’s violent attacks on his fellow Liberal, Prime Minister Mackenzie King, and his opposition to the centralization of power in Ottawa. Hepburn’s feud with King was a factor in his resignation in 1942. Between October 1942 and August 1943, before a general election was called, two men served in Hepburn’s stead: Gordon Daniel Conant and Harry Corwin Nixon.

Drew, Kennedy and Frost: 1943─61

In the 1943 election, the Progressive Conservative party led by George Drew formed the government. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, a socialist party, formed the official opposition.

Drew’s government vigorously promoted immigration, especially from the British Isles, and a series of reforms. Like Mitchell Hepburn, Drew fought with the federal government over attempts to centralize power. While the PCs won the 1948 election, Drew lost his seat. Rather than run again in a by-election, Drew shifted to federal politics. Thomas Kennedy served briefly as interim premier until Leslie Frost won a Progressive Conservative leadership convention in 1949.

Frost adopted a more co-operative attitude with the federal government, a major reversal in Ontario’s policy. He shared the developmental objectives of Liberal ministers in Ottawa such as C.D. Howe, and the two governments co-operated on major projects such as the St. Lawrence Seaway, the TransCanada Pipeline and the development of nuclear power. Frost led the PCs to three sweeping majority governments in 1951, 1955 and 1959. He resigned in 1961.

Robarts, Davis and Miller: 1961─85

Following Leslie Frost’s resignation, John Robarts was selected as leader of the Progressive Conservative party. Robarts and his party won majority governments in the next three elections (1963, 1967 and 1971). Like Frost, Robarts and the premier who followed him, William Davis, were low-key and down-to-earth. Both strove to minimize conflict between Conservative Ontario and the federal government, which was usually headed by the Liberals. Robarts tried to work out an accommodation that would satisfy Quebec and keep it in Confederation through his Confederation for Tomorrow Conference in 1967.

When Robarts retired from politics in 1971, Davis was chosen to lead the party. Davis led the PCs to two minority governments, in 1975 and 1977, and one majority government, in 1981. Notable aspects of Davis’s tenure include his strong support of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in patriating and reforming the Canadian Constitution, and his choice to fully fund separate schools. Davis resigned just a few months before the 1985 general election. In February, Frank Miller was selected to replace him. During the 1985 election, held in May, the PCs won 52 seats, enough to form a minority government in the 125-seat legislature. However, under the leadership of David Peterson, the Liberals joined forces with the New Democratic Party to form a minority government of their own. Peterson became premier, ending 42 years of Progressive Conservative rule in the province.

Peterson and Rae: 1985─95

David Peterson’s minority Liberal government had a rocky relationship with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. A reluctant supporter of Mulroney’s 1987Meech Lake Accord, Peterson strongly opposed the federal free trade initiative with the United States the same year. Peterson lost the next election to Bob Rae, who formed the first provincial New Democratic Party government in Ontario’s history. In an effort to reduce the provincial deficit, Rae imposed unpaid days off on public sector employees. Known as “Rae Days,” the policy divided the NDP and their labour-movement base. After serving his mandate, Rae lost to Mike Harris and the Progressive Conservatives in 1995.

Harris and Eves: 1995─2003

Mike Harris’s “Common Sense Revolution,” which included lower taxes, reduced social services and smaller government, lost some support from the public, but his government still won re-election in 1999. The Progressive Conservatives captured 59 of the 103 seats in the newly reduced Legislature but carried only 45 per cent of the popular vote. When Harris suddenly resigned as premier in 2002, he was replaced by former deputy premier and minister of finance Ernie Eves. Although more moderate than Harris, Eves and his party were criticized for a failed effort to privatize the province’s power system and the presentation of the 2003 budget in an auto-parts plant rather than in the Legislature.

McGuinty: 2003─13

The 2003 election was a landslide victory for the Liberal Party under Dalton McGuinty, which won 72 of the Legislature’s 103 seats and 47 per cent of the popular vote. McGuinty won another majority in 2007 after his main opponent, Progressive Conservative leader John Tory, damaged his own campaign by making a controversial pledge to extend public funding to faith-based schools. In his second term, McGuinty implemented the unpopular harmonized sales tax (HST), which replaced the provincial sales tax and the federal goods and services tax. Support for the Liberal Party began to slip, and in 2011 voters gave the party only 53 seats — one seat shy of a majority government. McGuinty resigned as premier in October 2012 (though he stayed on until 2013 when a new leader was chosen). His party faced criticism for its handling of labour relations with the province’s teachers, as well as for cancelling two gas-fired power plants. The power plants, located in ridings the Liberals needed to win in the 2011 election, were unpopular with residents. Cancelling them cost approximately $1 billion. The political scandal further evolved when McGuinty’s government refused to turn over documents to the legislative committee investigating the issue.

Wynne and Ford: 2013─Present

When Dalton McGuinty resigned as premier in 2012, the Liberal Party held a leadership convention. In 2013, Kathleen Wynne, former education minister in the McGuinty government, was elected leader of the party. She became both Ontario’s first woman premier and Canada’s first openly gay premier.

In the spring of 2014, the Progressive Conservatives and the New Democratic Party refused to accept the budget Wynne’s minority government tabled, triggering a snap election. Both the NDP and the PCs hoped to gain ground on the scandal-plagued Liberals. Wynne’s campaign, however, was ultimately successful, as she and her party formed a majority government, winning 59 seats to the PC Party’s 27 and the NDP’s 21. The next four years saw a decline in Wynne’s approval rating, which fell below 20 per cent in late 2016 and failed to recover as the end of her term neared. The Liberals’ unpopularity was tied in part to the increased cost of hydroelectricity and the government’s partial privatization of Hydro One in 2015.

Turnout for the 2018 general election was the highest it had been since 1999 — 56.7 per cent of the electorate voted. PC Party leader Doug Ford won a majority with 76 of the 124 seats in the Legislature and nearly 41 per cent of the popular vote. The NDP, under Andrea Horwath, gained official opposition status, more than doubling its seat count to 40. The Liberals met a devastating end to nearly 15 years in power, their seven seats falling short of the eight required for official party status. In her concession speech, Kathleen Wynne resigned as leader. Green Party leader Mike Schreiner won the first Green seat in Ontario history, taking the riding of Guelph.

While voter turnout in 2018 was historically high, voter turnout in Ontario’s next general election, in 2022, was the lowest in the province’s history. Only 43.5 per cent of eligible voters cast a ballot, several percentage points lower than the previous record low of 48.2 per cent in 2011. Ford’s PC Party again won a majority, increasing their seat count to 83. As in 2018, they did so with nearly 41 per cent of the popular vote. The remaining results were also similar to those of 2018. The NDP again formed the official opposition, though their seat count dropped to 31 and Horwath resigned as party leader. The Liberals won eight seats, and the Green Party and an independent candidate one each. Liberal leader Steven Del Duca also resigned, and his party again failed to obtain official party status. (In 2018, the PC majority changed the threshold for official party recognition to 10 per cent of the Legislature’s seats, increasing the requirement from 8 seats to 12.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom