Founding

First printed on 12 December 1828, The Vindicator was established by Dr. Daniel Tracey. Born in Ireland in 1794, Tracey — an Irish-Catholic and physician — left his British-dominated homeland in 1825, settling in Montréal, where he became the voice of the Irish population. Tracey was heavily influenced by Jocelyn Waller’s The Canadian Spectator, which was founded in 1822 and ended with his death in 1828. Waller’s newspaper was an ally of Louis-Joseph Papineau and the Patriotes, supporting reforms to the colonial political system. After Waller’s death, this torch passed to Tracey and The Vindicator.

The Tracey Years (1828‒32)

Under Tracey, the newspaper initially focused on promoting the political emancipation of Irish Catholics from British dominance. Though he was a supporter of the Parti canadien/Parti patriote, Canadian issues were secondary. This changed, however, when Tracey was forced to sell his newspaper’s shares to a group that included Ludger Duvernay, Denis-Benjamin Viger and Édouard-Raymond Fabre, after the newspaper went through financial difficulties. Though the newspaper’s new owners did not want Tracey to ignore Ireland, they wanted him to focus on Lower Canadian issues.

Tracey shared Ludger Duvernay and La Minerve’s radical ideology, especially with regard to the Legislative Council. On 3 January 1832, he wrote that “[i]t is quite an absurdity to think that about eight to ten men with scarcely common talent, and no better interest in the country than others, can act with all the caprice that this body does.” Like Duvernay, he often wrote that the Council should be abolished; both were arrested and imprisoned as a result. According to historian Yvan Lamonde, this arrest was an important moment, as it strengthened the bond between French Canadian and Irish reformers in Lower Canada. Until then, French Canadians had viewed Irish immigrants with distrust. Unfortunately, Tracey passed away shortly after. He died in July 1832 during the cholera epidemic; he was treating Irish immigrants for the disease.

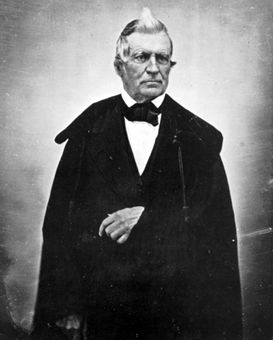

The Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan Years (1833‒37)

The Vindicator being the only English-language newspaper that supported the Patriotes, its owners were keen that it continue after Tracey’s death. In April 1833, Dr. Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan took over editorial duties. Like Tracey, O’Callaghan was an Irish immigrant, a physician and a supporter of the Patriotes.

In the period leading to the Rebellion, the newspaper continued to side with the party’s radical agenda. For one, O’Callaghan continued to attack the Legislative Council. On 3 September 1833, he wrote: “In every political struggle in which the country has been engaged for these years past, they have shown themselves to be violent partizans [sic] against the people.…” The newspaper also upheld the 92 Resolutions, calling them the foundation of Lower Canada’s “new Constitution.” It even defended French Canadians from attacks by the Tory press and argued that it was the Patriotes, not the British Party, that were the true allies of the Irish community. O’Callaghan also expanded the scope of the newspaper, giving international news more space. For instance, he often linked insurrections that were happening around the world — such as in Poland, Belgium and Ireland — with the Patriote movement.

O’Callaghan and The Vindicator were nonetheless in a delicate position. Though he could count on the unrelenting support of the radical members of the Irish community, many of its more moderate elements favoured the British Party. The French Canadian nationalism and radicalism that was promoted by the party after the 92 Resolutions made many Irish sympathizers uncomfortable. As a result, O’Callaghan avoided divisive topics such as the French Canadian character of the party and seigneurial tenures.

Nevertheless, O’Callaghan and The Vindicator remained loyal to the party, even pressing for armed rebellion. Following the Russell Resolutions, O’Callaghan incited his readers to take up arms and rebel: “Our rights must not be violated with impunity. A howl of indignation must be raised from one extremity of the Province to the other… Henceforth, there must be no peace in the Province, no quarter for the plunderers. Agitate! Agitate!! AGITATE!!!”

Closure

In early November 1837, the newspaper ceased to exist. On the night of 9 November, O’Callaghan’s office and printing equipment were destroyed by members of the Doric Club, a Tory paramilitary group that opposed the Patriotes. Similar to many Patriotes, O’Callaghan eventually escaped to the United States when the government issued a warrant for his arrest. While in the United States, O’Callaghan continued to work with his Patriote colleagues, such as Ludger Duvernay and Robert Nelson, trying to ignite American support for their cause. He even travelled as far south as Philadelphia to gain financial and military support (see The Early American Republic and the 1837‒38 Canadian Rebellion).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom