What’s a Totem Pole?

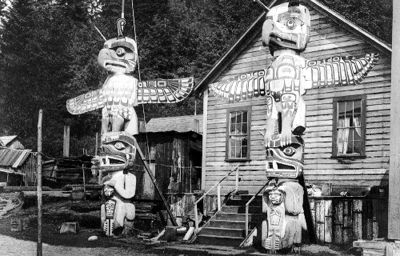

A totem pole or monumental pole is a tall structure created by Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples that showcases a nation’s, family’s or individual’s history and displays their rights to certain territories, songs, dances and other aspects of their culture. Totem poles can also be used as memorials and to tell stories. Carved of large, straight red cedar and painted vibrant colours, the totem pole is representative of both coastal Indigenous culture and Northwest Coast Indigenous Art.

History of Totem Poles in Canada

Archeological evidence suggests that the northern peoples of the West Coast were among the first to create totem poles before the arrival of Europeans. The practice then spread south along the coast into the rest of British Columbia and Washington state. First Nations credited with making some of the earliest totem poles include the Haida, Nuxalk (Bella Coola), Kwakwaka’wakw, Tsimshian and Łingít. The Coast Salish people also make carvings out of cedar, but they are not really totem poles. The Coast Salish carve planks of wood that attach to the interior or exterior of their ceremonial houses.

The arrival of Europeans altered the construction of contemporary poles, as they introduced new materials and carving tools to Indigenous peoples through trade in the 19th century. Colonization also threatened the very existence of totem poles. Beginning in the 19th century, the federal government sought to assimilate First Nations by banning various cultural practices in the Indian Act, including the potlatch, which is the ceremony during which totem poles are often erected. Until the potlatch ban was lifted in 1951, totem poles were displaced and appropriated by Europeans, taken away from their homes and brought to museums and parks around the world. Christian missionaries also encouraged the cutting down of totem poles, which they saw as obstacles to converting Indigenous peoples. Poles commissioned by non-Indigenous peoples during this time were, and still are, considered culturally insensitive. It was only in 2017 that the Haisla First Nation was able to remove and replace an old monumental pole that was not carved or erected according to their customs with a new, Haisla-designed one.

After amendments to the Indian Act, the 1950s saw the beginnings of increased Indigenous efforts at reclaiming totem poles. New poles were commissioned for museums, parks and international exhibits; and in the late 1960s, totem poles were once again being raised at potlatches. As such, the totem pole can be seen as a symbol of ongoing survival and resistance to cultural and territorial encroachment. Many Northwest Coast communities have struggled to repatriate totem poles taken from them by colonial forces for sale or display elsewhere. In 2006, the Haisla successfully repatriated from a Swedish museum a pole taken in 1929 (see Repatriation of Artifacts.)

Totem Pole Designs and Meanings

Different First Nations have their own methods of designing and carving totem poles. The Haida, for example, are known to carve creatures with bold eyes, whereas the Kwakwaka’wakw poles typically have narrow eyes. The Coast Salish tend to carve representations of people on their house posts, whereas the Tsimshian and Nuxalk tend to carve supernatural beings on their poles.

In general, however, poles are skilfully carved of red cedar and are usually painted black, red, blue, blue-green and sometimes white and yellow. While paint was not used much in the past as part of the design, it is commonly used today. Poles vary in size, but house front poles can be over one metre in width at the base, reaching heights of over 20 m and generally facing the shores of rivers or the ocean.

Animal images on totem poles depict creatures from family crests. These crests are considered the property of specific family lineages and reflect the history of that lineage. Animals commonly represented on the crests include the beaver, bear, wolf, shark, killer whale, raven, eagle, frog and mosquito. The crest animals represent kinship, group membership and identity, while the rest of the pole may represent a family’s history.

Some poles also feature supernatural beings or humans, each with their own particular importance and significance to the nation or individual who commissioned it and to the person who carved it.

The cultural appropriation of totem poles by Europeans over the years has created and popularized the false idea that poles display social hierarchy, with the chief at the top and the commoners at the bottom. In fact, depictions of people are not usually found at the top of a totem pole and in some cases, the most important figure or crest is at the bottom. Totem poles do not depict a nation’s social organization in a top-down method; rather, they tell a story about a particular nation or person’s beliefs, family history and cultural identity.

Types of Totem Poles

There are various types of poles, each with their own purpose and function. Some, for example, are specific to death and burial practices. Memorial poles are erected in memory of a deceased chief or high-ranking member. The poles depict the member’s accomplishments or family history. Mortuary poles also honour the deceased. Haida mortuary poles include a box at the top where the ashes of the chief or high-ranking member are placed.

Some poles are used to depict families and lineages. House posts, placed along the rear or front walls of a house, are poles that, on the one hand, help to support the roof beams and, on the other hand, tell about family lineages. Similarly, house front or portal poles are monuments at the entrance of a home that describe family history.

Welcoming poles do what their name suggests — welcome visitors. First Nations sometimes erect poles as a means of greeting important arriving guests during a feast or potlatch. The Hupacasath First Nation has well-known welcome figures on its territory. With arms outstretched, the figures carved into the poles welcome and guide the guests during their travels. Another type of greeting pole is the speaker’s post — a carved figure of an ancestor. An appointed speaker announces the names of visitors from behind the post. In a sense, this allows the ancestors, speaking through the appointed speaker, to also welcome the guests.

Legacy poles commemorate important and historic events. In 2013, the Haida erected a legacy pole as a way of commemorating the signing of the Gwaii Haanas Agreement (1993), a groundbreaking document between the Haida and the Government of Canada that sets out the government-to-government and management relationship for Gwaii Haanas. Carver Jaalen Edenshaw supervised and worked on the legacy pole, which became the first monumental pole raised in the protected Gwaii Haanas territory in over 130 years.

Poles can also be used as a means of healing and education. Artist Charles Joseph’s totem pole, erected on 3 May 2017 in Montréal, serves as a reminder of the residential school system. A residential school survivor, Joseph wanted to express his emotions about those painful years, while also working towards reconciliation. Similarly, artist and residential school survivor Isadore Charters has shared his personal story with young people through a totem pole project. Charters carved a healing pole that tells about his eight-year experience at a Kamloops residential school. The pole is also intended to foster healing.

Shame poles or ridicule poles are less common elements of the tradition, but traditionally were used to mock and criticize neighbours for being insulting, offensive or for not paying back debts. These poles were also used by chiefs to belittle their political rivals. Contemporary communities may use similar tactics now in protesting external — government or corporate — entities.

Totem Pole Carvers

Not just anyone can carve a totem pole. Specialists known as carvers are commissioned by First Nations or individuals to make them. The wood the carvers use to make a pole is preferably taken from the traditional territory where it will be placed. Using tools like adzes (curved knives) and chisels, the carvers work from the bottom of the wooden pole, after it has been stripped and cleaned, and work upwards, carving over lightly drawn designs.

Older generation carvers such as Charles Edenshaw (c. 1839–1920), Charlie James (1867–1938) and Mungo Martin (1881–1962) inspired artists like Ellen Neel (1916–66), Henry Hunt (1923–85), Bill Reid (1920–98), Douglas Cranmer (1927–2006), Tony Hunt (1942–), Norman Tait (1941–2016) and Robert Davidson (1946–) to continue the tradition and themselves inspire a new generation. Today, their work, and the work of next generation carvers, such as Jaalen Edenshaw, can be seen in museums, galleries, on traditional territories, in parks like Stanley Park and Thunderbird Park in British Columbia, and elsewhere.

Significance

Totem poles are important expressions of specific Indigenous cultures along the Northwest Coast. Despite the threats posed by cultural, political and territorial encroachment, the art of totem pole carving has survived. While the totem pole has been used wrongly as a generic symbol of Canadian identity over the years, it is important to understand that these sacred monuments are specific to certain First Nations, and therefore carry deep meaning for those peoples and their ancestors.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom