Definition

Broadly speaking, “country food” can refer to a wide variety of cuisines prepared by locals in what is often a rural area. Typically, when used in Canada, and in reference to Indigenous peoples, country food describes traditional Inuit food. This includes marine life, such as shellfish, whales, seals and arctic char; birds and land animals, such as ducks, ptarmigan, bird eggs, bears, muskox and caribou; and plant life, including roots and berries. While some Inuit prefer the term “Inuit food” to refer to their traditional cuisine, the term “country food” is used more broadly. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the leading national Inuit organization in Canada, has used “country food” in its reports and research on Inuit health and food insecurity.

Preparation

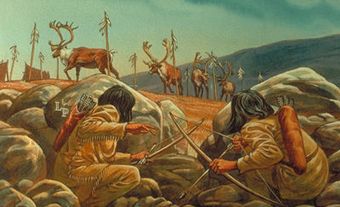

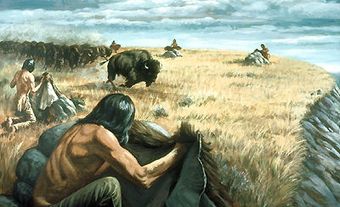

The Inuit harvest, trap, hunt and fish for country food. To prepare such food for consumption, roots and berries must be cleaned, and animals require both cleaning and skinning. Traditional tools such as the ulu (a type of knife) are used in these preparation processes.

The Inuit use every part of the animal, if not for food than for other functions, such as clothing (animal hides and furs), heating (seal oil) and the making of various traditional tools (bones and sinew). In some communities, the predigested plant foods found in the stomachs of caribou are also consumed.

Meat is prepared in a variety of ways, depending on community and personal preferences. It can be boiled, dried, fermented, frozen, fried or eaten raw. Muktuk (or maktaaq) — pieces of whale skin with blubber (often from a narwhal, bowhead or beluga) — is a well-known country food consumed by the Inuit and sought after by tourists and food enthusiasts. Usually served raw, muktuk is an excellent source of vitamin C.

Health Benefits

The traditional Inuit diet — high in healthy fat and protein — is designed for Arctic living, as it keeps the Inuit energized and protects against starvation and death. Animal fat fuels hunters and warms the community. Historically, hunters avoided lean animals, such as rabbits, because without the appropriate fat content, the meat offered little nutrition and could lead to starvation, if relied on as the main or sole source of food. (See also Rabbit Starvation.)

Country food also has nutritional benefits. Vitamins A and D are plentiful in fish oils, and vitamin C is found in various meats, crowberries and raw kelp. Fish and meat also contain B vitamins and iron. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fish, have anticlotting effects and help to lower triglycerides (body fats). Fish heads provide a good source of calcium. Even the fat of wild animals is considered healthy because its is less saturated than the fat commonly found in many processed foods.

The benefits of country food go beyond nutritional value. Harvesting requires outdoor activity, which can often be physically demanding. Such exercise prevents against illnesses partly associated with sedentary living, such as obesity and heart disease. Hunting and cooking with family and friends also keeps the community close and allows for the sharing of cultural practices.

Did You Know?

The nutritional value of country foods is thought to be one of the main reasons for which the Inuit did not fall victim to diseases of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, such as scurvy, which killed many early European explorers in the Arctic. (See also Arctic Exploration and Franklin Search.)

Cultural Significance

To the Inuit, country food is about more than nutrition; it is also an expression of Inuit identity and culture. When elders teach young hunters how to subsist off the land, they are also teaching them about the lands and waters of the Arctic, and about the role that animals play in Inuit lives. Hunting for and preparing country food is a way of transmitting traditional knowledge.

Country food is also a way to promote and maintain self-sustaining communities. Some Inuit communities share food — a common cultural and historic practice. Sharing also offsets the high cost of food found in grocery stores and provides sustenance for those who might otherwise go hungry. Sharing food with community members is a form of respect, especially for elders.

In a spiritual way, country food nurtures the special connection between the Inuit and nature. It connects people to the earth, to the animals, to the waters and to one another. Country food is also a way of giving thanks to the animal that was sacrificed to provide sustenance for so many.

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity describes lack of access to sufficient and healthy food. According to the 2007–08 Inuit Health Survey, 70.5 per cent of Inuit adults live with food insecurity. Daily consumption of country food has decreased over time, from 23 per cent in 1999 to 16 per cent in 2008. Factors influencing food insecurity in the Arctic include socioeconomic changes, environmental concerns, hunting restrictions and financial challenges.

Socioeconomic Changes

Colonization profoundly altered the Inuit diet and way of life. Contact with European whalers began in the early 1700s, followed by relations with explorers in the early 1800s. Among other factors, the introduction of European goods, such as guns and steel tools, contributed to an economic dependence on European products and a decline in the use of traditional tools. Trading with the Hudson’s Bay Company only exacerbated this dependence over time.

The biggest changes to Inuit lifestyles arguably came in the 20th century. During the Cold War, the federal government became increasingly concerned about Arctic sovereignty. This turned political and military attention to the North and resulted in the building of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line along the Arctic coast, from Alaska eastward to Baffin Island and continuing to Greenland. ( See also Early-Warning Radar.) The DEW Line polluted and altered Arctic landscapes — problems that continue to impact Inuit communities. During the mid-1900s, the federal government also forcibly relocated Inuit families, at least partly as a means of populating isolated areas in the North for the purposes of Arctic sovereignty.

The mid- to late-1900s also brought with it a wage economy and the creation of permanent settlements in the North. Youth — many of whom were sent to residential schools — became detached from traditional ways of life, including the harvesting of country food. Socioeconomic changes therefore also contributed to a loss of culture. Subsistence patterns changed as hunters became more reliant on guns and motorized transport for hunting (as opposed to traditional tools and dogsledding), and on food shipped from outside the Arctic.

An imposed Westernized diet consists of expensive, flown-in foreign foods, such as fresh produce and certain dairy products, and inexpensive processed foods, which are more accessible but less healthy than country foods. Such products contain higher levels of sugar, salt and trans fats, and therefore contribute to higher rates of type 2 diabetes and heart disease among the Inuit. Poor nutrition is also linked to obesity, psychological development and maternal and child health, as well as higher rates of tuberculosis among the Inuit.

Environmental Concerns

Warmer temperatures, resulting in the melting of ice caps and a reduction in snow cover and permafrost, have profoundly affected the climate and ecosystems in Arctic Canada. (See also Climate Change.) Some animals, such as the muskox and polar bear, have been moving to new areas to survive. Inuit hunters are therefore forced to follow such animals along new and distant travel routes. Unpredictable weather patterns have also made sea ice hunting more dangerous and have shortened the hunting season, as the ice no longer freezes as quickly or as completely as it once did. Inuit food security is threatened by hunters’ increasing inability to harvest country food.

Pollution also poses health and safety hazards to the consumers of country food. Some Arctic animals are found to contain heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Inuit who eat foods containing these pollutants may be more susceptible to respiratory illnesses, birth defects and cancer. The Northern Contaminants Program (NCP), established by the federal government in 1991, found in 2009 that while levels of many POPs were declining, levels of some contaminants, such as mercury, were increasing. In addition to providing Northern communities with information about food sources, the NCP also works to reduce and eliminate contaminants in country foods.

Hunting Restrictions

Regulatory hunting legislation is another factor impeding access to traditional food. As a means of protecting animals threatened by climate change, the federal government has imposed limits on hunting. The Firearms Act (1995) imposes legal requirements on firearm registration and the obtaining of licenses that, while meant to ensure safety among other factors, also increases the cost and time associated with hunting traditional food sources. The Species at Risk Act (2002) restricts the number and type of animals hunted, and the time of year of hunts. Some policy documents, such as the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement and the Territorial Lands (Yukon) Act, provide the Inuit with more control over their land and wildlife. However, as the climate continues to warm and become more unpredictable, it is likely that restrictive legislation will become more common, further limiting what foods the Inuit can hunt.

Inuit hunters’ freedom is also restricted by animal rights activism. Most often, activists protest the seal hunt, which they allege to be a cruel practice. (See also Seal Hunt Controversy.) In 1983, Greenpeace and other activists successfully influenced the European Union’s ban on sealskin products made from white coat harp seal pups. While the legislation exempt the Inuit, the reputation of sealskin in general was ruined. In 1984, the average income of a seal hunter in Resolute Bay dropped approximately 98 per cent. The Inuit maintain that seal meat is an essential part of their diet, economy and culture. Contrary to popular opinion, sealers now undergo mandatory training to ensure that hunting practices are humane. Seal meat also has health benefits: it is rich in zinc, iron and various vitamins. Sealskin can be used to make waterproof clothing. Not considered endangered, seals provide diverse value to the Inuit. Angry Inuk (2016), a documentary directed by Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, seeks to highlight Inuit voices and perspectives in the controversial conversation about the seal hunt.

Financial Challenges

In many cases, the high cost of hunting equipment (which is flown in from the South) inhibits hunters’ ability to provide country food for their communities. An all-season hunting outfit can cost about $55,000, which is more than double the average income in Nunavut. While there are some hunting organizations and harvester support programs that offer subsidies, the costs remain high. As a result, many Inuit are discouraged from pursuing hunting as a full-time endeavour.

Alternative healthy options to country food, such as dairy and fresh produce, are similarly expensive because they are flown in. In 2016, the CBC reported that at a grocery store in Iqaluit, a 4-litre jug of milk cost just over $10. While some Inuit use milk from seals and caribou, this is not readily available, and especially not in bulk. In 2017, a Business Insider report found that a Nunavut grocery store charged just over $16 for five ears of corn, and $12 for two heads of broccoli. Since these prices are often outside the budget of most families, the Inuit are limited in how much fresh produce and dairy they can purchase. The 2017 Nunavut Food Price Survey, conducted by the Nunavut Bureau of Statistics, found that people in Nunavut pay about two times more than other Canadians for the same food items.

In 2011, the Canadian government created a subsidy program, Nutrition North Canada, aimed at providing healthy food at a reduced cost. However, a 2017 report by Tracey Galloway, a researcher from the University of Toronto, argues that the program is failing because of a lack of accountability and strict regulations. With certain foods out of their financial reach, the Inuit mainly consume a combination of country food and less expensive non-perishable food from grocery stores.

Promoting Country Food

Despite ongoing challenges to food security, traditional harvesting is still alive in Inuit communities. The 2007–08 Inuit Health Survey states that more than two-thirds of households in Nunavut had an active hunter in the home. Country food remains integral to Inuit identity and overall well-being. When Inuk photographer Barry Pottle asked Inuit why country food was important (as part of a photo essay he created in 2015), they replied: “We need Inuit country food to feel who we are!” “[They are] not just foods we crave, but they are a part of us” and “It’s…good for the spirit, and eating my own country means healing.” These answers demonstrate the ongoing importance of traditional food to Inuit culture and survival.

As a means of protecting those traditions, policy-makers continue to develop strategies for food security. The Nunavut Food Security Coalition, which unites representatives from the Government of Nunavut and four Inuit organizations, seeks to ensure all people in Nunavut “will have access to an adequate supply of safe, culturally preferable, affordable, nutritious food, through a food system that promotes Inuit societal values, self-reliance, and environmental sustainability.” The federal government similarly supports sustainable food in the North and seeks to address both the high costs of food and concerns about contaminants in country food. A variety of non-profit organizations, independent researchers and Inuit organizations — namely Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami — also produce studies on food security, with the goals of improving the well-being of Inuit in Canada.

In recent years, education programs in the North have incorporated traditional food and hunting practices into various curricula. Developed by the Nunavut Department of Education in 2007, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Education Framework for Nunavut Curriculum focuses on the promotion of Inuit values and culture in schools, which includes knowledge about traversing and living off the land. Nunavut Arctic College provides the Piqqusilirivvik Program, a series of courses on topics including hunting and fishing, survival skills and land and water knowledge. The program incorporates Inuit games, language and stories into the course work.

Television and film projects have also made efforts to promote Inuit culture. Niqitsiat (Healthy Food), a cooking show airing on APTN from 2009 to 2018, explored ways to combine traditional and non-traditional food in a healthy way. Hosted by Inuk cook Rebecca Veevee, Niqitsiat showcased Inuit food, such as muskox, caribou, seal and arctic char. Veevee almost always spoke Inuktitut and used an ulu when preparing meals, thereby reinforcing other aspects of Inuit culture on the show. Documentaries such as Angry Inuk (2016) also bring attention to issues of food security and the benefits of the controversial seal hunt to Inuit communities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom