History and Development

Following Captain James Cook's visit to the west coast of Vancouver Island in 1778 a number of Nuu-chah-nulth word lists circulated among maritime fur traders. The Pacific Ocean depot for the land-based fur trade of the West Coast, a settlement called Astoria — later Fort George, and now Astoria, Oregon — was at the mouth of the Columbia River. Here, the French spoken by interior traders, the English and Nuu-chah-nulth of the coastal traders and the Salishan languages of neighbouring people all combined with the Lower Chinook of the immediate area to form an evolving Chinook Wawa. Over the next century, the language steadily adopted more English words.(See also Indigenous Languages; Northwest Coast Language Families).

In 1825 Fort Vancouver, a settlement 140 km inland on the Columbia River, became the locus of Chinook Wawa when the Hudson’s Bay Company established its headquarters there. Fort Vancouver administered trading communities from California to Alaska and knowledge of Chinook Wawa spread through these networks.

Roman Catholic priest Modeste Demers arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1838 and soon produced a dictionary and written materials which he used in his missions to British Columbia. With the establishment of the United States border on the 49th parallel in 1846, Fort Vancouver was no longer part of British North America, and some personnel moved north to Victoria. These people became the administrative core of the nascent British Columbia and brought the use of Chinook Wawa with them. The language was used by Protestant and Catholic missionaries in Canada as well as the Shaker Church, which combined elements of Catholic, Protestant and Indigenous religions.

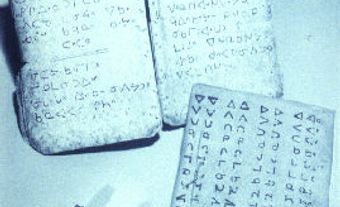

As Chinook Wawa experienced growth during the Fraser Canyon and Cariboo gold rushes from 1858 to 1865, several dictionaries entered circulation. For many years the language was used in British Columbia as the working language of canneries and mills, and was often learned by early Chinese immigrants. It was used extensively by Indigenous peoples on both sides of the border, and was also used by nations both in resistance and in negotiating peace treaties in the State of Washington. Jean-Marie Lejeune, a Roman Catholic priest, developed a writing system using French shorthand and published a newspaper from 1891 to 1904 called the Kamloops Wawa which remains the largest collection of written Chinook Wawa.

Usage declined rapidly through the early 20th century, due to an influx of English-speaking settlers, residential schools that discouraged the use of Chinook Wawa, devastating diseases, and economic and social dislocation. Today it survives in the hundreds of place names throughout British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest and in the vocabulary of some long-time British Columbia residents. Chinook Wawa persists as a creole on the Grand Ronde Reservation in Oregon and there are several efforts to revive it elsewhere. The motto of the State of Washington is Alki, meaning "hope for the future." Iona Campagnolo used Chinook Wawa in her swearing-in ceremony as Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, saying, “Konoway tillicums klatawa kunamokst klaska mamook okoke huloima chee illahi.” which translates as, “Everyone was thrown together to make this strange new country.”

Grammar and Vocabulary

Chinook Wawa takes a large part of its vocabulary and some of its grammar from the Lower Chinook language. Until its later development French contributed the next largest number of words, many retaining the definite article and Québécois accent. The word order adopts the Subject-Verb-Object of French/English not the Verb-Subject-Object of the original Lower Chinook language. Its small vocabulary of around 700 words is overcome through the use of words with context-dependent meanings, compound words and circumlocutions. It retains a “tl-” sound that derives from a whispered "L" (lateral fricative) unfamiliar to English and French speakers. There is no standard spelling convention so words are generally spelled phonetically.

Grammar Examples

Nika nanitch kiutan — I see the horse. (Note Subject-Verb-Object word order.)

Delate skookum mika — [very strong you] — you are very strong. (Note Verb-Subject optional pattern.)

Alki nika potlatch moxt tala kopa mika — [future I give two dollars to you] —I will give you two dollars. (Note future tense marker.)

Wake yaka klatawa — [not he goes] — he doesn't go. (Note adverbial negative in sentence initial position.)

Vocabulary Examples

Words derived from Lower Chinook unless noted otherwise:

Wawa [fr Nootka] = word, speak, discuss, language (cf. Chinook Wawa, Kamloops Wawa newspaper).

Hyak = fast (cf. Hyak Festival in New Westminster BC).

Skookum [fr Salish] = robust, strong.

Chuck [fr Nootka] = water (cf. Skookumchuck Narrows, BC, the salt chuck, “the ocean, salt water”).

Siwash = [pronounced siWASH] natural, untamed, also Indigenous person. (cf. Siwash Rock in Stanley Park). Only considered derogative if pronounced SAIwash.

Cheechako [chee = new, chako = come] = a newcomer, greenhorn (cf. Ballads of a Cheechako by Robert Service).

Hyiu [fr Nootka] = a lot, Muckamuck = a lot of food — (cf. highmuckymuck — popular term connoting self-important person, possibly referring to someone who sits at head table).

Tzum = mixed colours, a mark, writing - (cf. Chum Salmon, a species with markings on its side).

Klahanie = outside (cf. CBC television program in the 1960s and 1970s about wilderness).

Yakwatin = belly

Latet [fr French la tête] = head. Note definite article and indication of Québec accent.

Stick [fr English] = mast, tree, wooden. (cf. the sticks, a common BC expression for forest).

Tillikums = people, friends (cf. Tillicum, the mascot for Vancouver’s centennial celebrations).

Muckamuck = to eat, food (cf. high muckamucks — those in power, the ones with a lot of food).

Potlatch = giving, a ceremony where goods are provided.

Klahowya = greetings, how do you do.

Tyee = chief.

A number of geographic features have names derived from Chinook Wawa, among them are numerous lakes like: Canim ("canoe"), Nanitch ("see"), Kikwillie ("deep"), Eena ("beaver"), Siam ("grizzly"), Mesachie ("bad"), and Wahpeeto ("potato").

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom