Dakota Peoples: Territory and Languages

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Dakota (Sioux) occupied what is now western Ontario and eastern Manitoba prior to 1200 AD, and western Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan prior to 900 AD. These populations later withdrew to the drainage basins of the Red, Mississippi and Rainy rivers, where they were located when first contacted by Pierre Radisson in 1659. By then the Siouan-speaking Dakota population had divided into three groups:

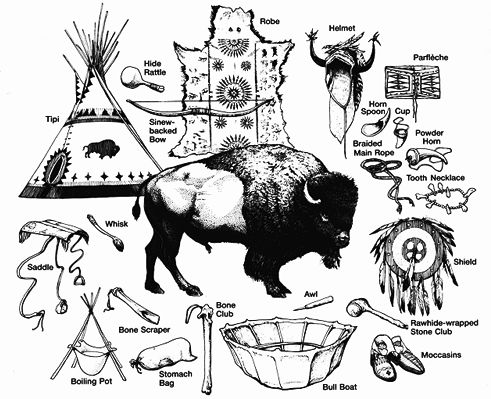

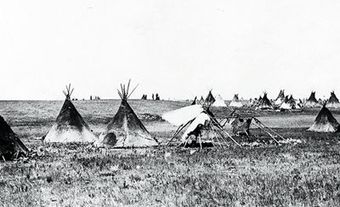

Farthest east, along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, dwelt the Dakota (Santee Sioux), who practised horticulture, occupied semi-permanent villages, harvested wild rice as a food staple and hunted buffalo (see Buffalo Hunt). After acquiring horses in the early 1700s, the Dakota expanded their territory from the Mississippi River to the Yellowstone River, and from the Platte River to the Qu’Appelle River. Hudson’s Bay Company records from Fort Qu’Appelle to Rainy Lake House (Fort Frances, Ontario) commonly mention the Dakota occupying that territory from the late 1700s.

Between the Mississippi and the lower Missouri River were the Nakota (Yanktonai Sioux), speakers of a similar dialect to the Dakota as spoken by the Assiniboine and Stoney of Canada. This population wintered along the wooded tributaries of the Mississippi and summered on the plains, hunting big game.

Farthest west along the Missouri River lived the Lakota (Teton Sioux), who were wholly mobile and largely dependent upon the buffalo.

Dakota and Lakota are dialects of the Sioux languages spoken on the prairies. Even though different in many respects, all three groups were politically united and referred to themselves collectively as Dakota (Nakota, Lakota) or “the allies.”

Colonial History

During the War of 1812, the Dakota pledged their alliance to Britain, in return for oaths of perpetual obligation. This alliance was betrayed at the Treaty of Ghent (1814), when Britain abandoned its Indigenous allies as a term of peace. The Dakota then drew closer to their lands in the United States; however, though land use in Canada decreased, the northern territory was never abandoned.

The western expansion of the Americans ended Dakota territorial sovereignty when, in 1862, the US military, after the Minnesota Uprising, drove some of the eastern population into Canada, where they took up reserve lands in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. A few Lakota, including Sitting Bull, moved into southern Saskatchewan following the Battle of the Little Big Horn (1876).

The Dakota have since been treated as political refugees by Canadian governments. They were not included in treaty negotiations, as were all other Plains Indigenous populations, and were expected to make their own future in Canada (see Treaties: Indigenous Peoples; Numbered Treaties). The Dakota became commercial farmers, producers of specialty crops, woodworkers, cattle ranchers, small-scale resource exploiters and labourers, traditions that are carried on today.

Self-government

The Dakota have long argued over their interests in Canada and the debt owed them for the War of 1812. Canada has consistently labelled the Dakota “American Indigenous peoples” or immigrants and, therefore, not owed the same level of obligation as the treaty people. Over the years this has meant less land for reserves, less support for economic development and less access to opportunities.

After years of struggle, the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation in Manitoba gained self-government on 1 July 2014. It was the first Indigenous nation in Manitoba and the Prairies to become self-governing. This agreement provides the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation with more control over its own affairs, including housing, education, public safety, financial administration and more.

Dakota Access Pipeline

In 2014, Texas-based company Energy Transfer Partners proposed to construct an oil and gas pipeline, known as the Dakota Access Pipeline, measuring approximately 1,900 km long, from the Bakken and Three Forks areas in North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. The pipeline threatens to come within 800 m (half a mile) of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose ancestral lands stretch throughout parts of North Dakota and South Dakota. Claiming the pipe could pollute a major water source (the Missouri River) and disturb the surrounding environment, Standing Rock and its supporters — including Dakota peoples and other Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada — protested the pipeline’s construction. Although President Barack Obama made efforts to block the construction of the pipeline before the end of his term in office, his successor, President Donald Trump signed an executive order on 24 January 2017 to advance its approval.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom