York Factory, also known as York Fort, Fort Bourbon by the French, and Kischewaskaheegan by some Indigenous people, was a trading post on the Hayes River near its outlet to Hudson Bay, in what is now Manitoba. During its life, it served as a post and later as a major administrative centre in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur trade network. It also bore witness to the largest naval battle to take place in Arctic Canada, the Battle of Hudson Bay in 1697.

Early Explorers and Fur Traders

In 1612, British naval officer Thomas Button was chosen to command an expedition to determine the fate of Henry Hudson, which directed him to search out the Northwest Passage. The nearby Nelson River was named for one of Button’s officers who died while the ship was anchored off the river’s mouth.

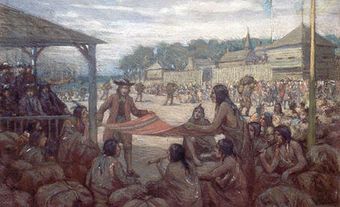

In 1682, explorer Pierre-Esprit Radisson headed a French expedition in the area. The newly formed Compagnie du Nord was looking to establish a permanent fur trading settlement in the North. After founding a fort on the south bank of the Hayes River, Radisson spent the winter skirmishing with American and British expeditions for control of the furs in the area – a campaign he eventually won. When Radisson returned to Quebec, however, his furs were seized, and he was assessed a 25 per cent tax, equalling his share of the profits.

Unhappy with his treatment by authorities in New France, Radisson was then enticed to rejoin the Hudson's Bay Company, which he had earlier been allied with. Receiving stock, gifts, and the title of Chief Director of Trade at Port Nelson, Radisson returned to the Hayes River estuary in the employ of the HBC.

Founding of York Factory

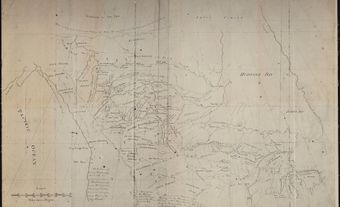

The first York Factory outpost was constructed in 1684 on the narrow peninsula that separated the Hayes and Nelson rivers. The location was key, as both rivers flowed from the heart of fur trading territory to the shores of Hudson Bay.

York Factory was named after the Governor of the HBC, the Duke of York. The word Factory was added to indicate that this was where the "factor" or chief trader of the area resided.

Because of the shallow mud flats along the mouths of the rivers, ships could not approach close to the fort, but were required to anchor 11 km away at Five Fathom Hole. Smaller sloops transported goods to and from the ocean-bound ships.

Battle of Hudson Bay

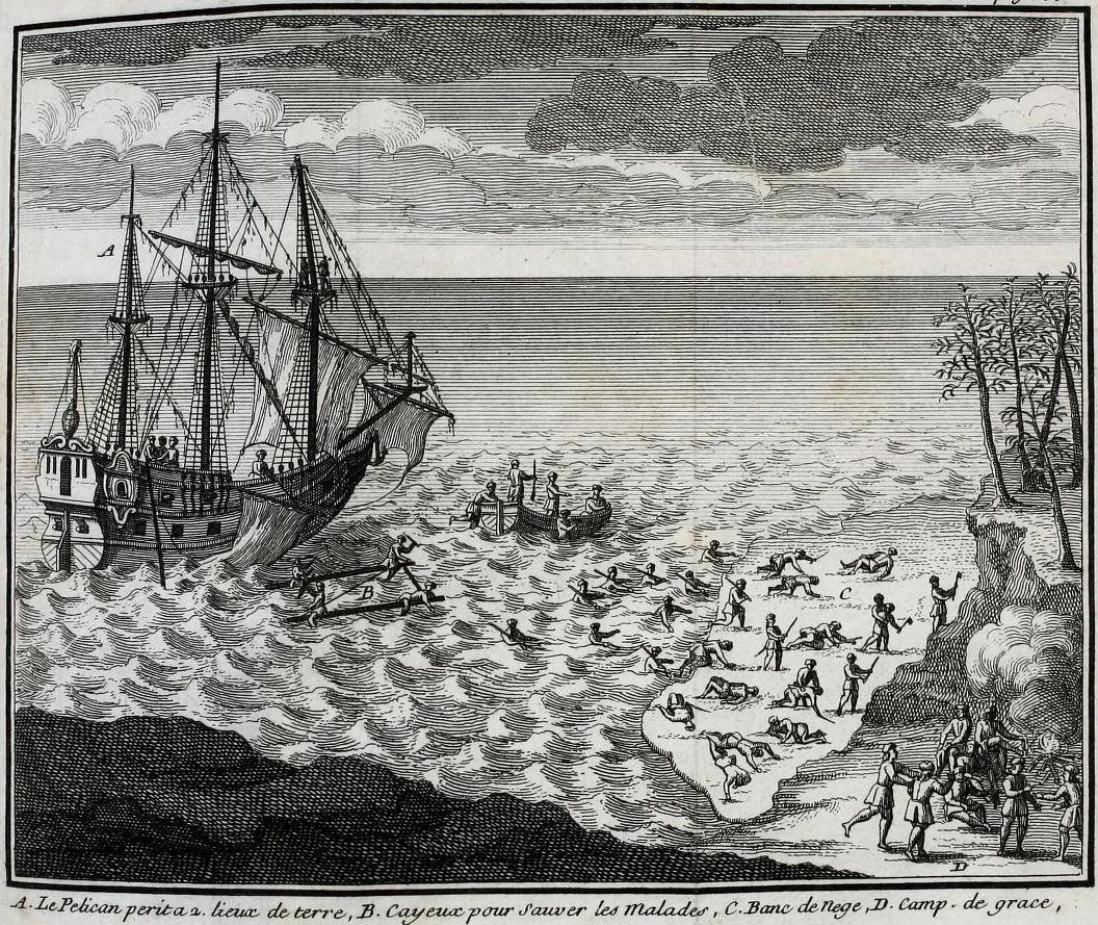

King William’s War – the North American theatre of the Nine Years’ War between England and France – was declared on 17 May 1689, but open conflict in Hudson Bay preceded it by three years. Throughout the conflict, French forces tried to capture enemy forts in and around Hudson Bay. One of these was York Factory. The French captured York Factory in 1694, only to have the English take it back a year later. Then, in 1697, a naval battle ensued in Hudson Bay between English and French forces. Captain Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville succeeded in taking York Factory for the French. The fort was later transferred back to the British after the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. (See also Battle of Hudson Bay.)

Floods and Relocation

The physical location of York Factory changed several times over its history. A flash flood on the Hayes River in 1715 put the outpost under more than a metre of water. The post’s governor, James Knight, viewed the buildings to be unrepairable, and moved the site 2.5 km downstream to higher ground. A French raid in 1782, followed by another flood in 1788, destroyed much of the fort. A search went out for the highest dry promontory on which to construct a more permanent site.

By the mid-1800s, York Factory had been rebuilt into a township of 30–50 buildings, taking the shape of an H. The main depot in the centre was the most dominant structure. Other buildings included guest houses, a doctor’s house, an Anglican church, a hospital, a library, cooperage, smithy, bakehouse and residences.

Still, the post did not endear itself to all concerned. HBC clerk Robert Ballantyne described York Factory in 1846 as, “A monstrous blot on a swampy spot, with a partial view of the frozen sea.” Chief Factor James Hargrave spoke of “nine months of winter varied by three of rain and mosquitoes.”

Northern Headquarters

York Factory grew in prominence after 1774, when the HBC began building fur-trading posts in the interior, to combat competition from the Montreal-based North West Company. Although the bulk of the trade soon moved inland, York Factory prospered as the administration and transportation hub, as well as HBC’s primary seaport. Trade goods for a dozen posts went inland and furs came out. In 1810, the HBC named York Factory as its headquarters for its new Northern Department.

The Hayes River had the required depth to handle the large canoes that came from the interior, making it the preferred route into what was then called Rupert’s Land. Canoes were eventually replaced by larger craft, called York boats in recognition of their final destination on the coast. York boats could handle up to six tonnes of freight.

Decline

In the end, York Factory succumbed to both the railroad and its own growth. In 1871, the railroad reached the Red River settlement in what became Manitoba. The HBC soon transferred its northern headquarters to Winnipeg, reducing York Factory to a coastal trading post. The last ship left York Factory in 1931.

The local environment, on its own, was not able to support the post and its population of Europeans, Metis and First Nations. Forest clearance and overhunting of local game increased the cost of operating the post, while local fur returns also became marginal. The post continued to decline until it was finally closed in 1957. Title of the property was transferred in 1968 to the federal government, which made it a National Historic Site.

Present Day

All that remains today at the site is a small clearing, the large depot and a small outbuilding. The depot has survived on the permafrost because of a number of engineering innovations. The large columns and beams were joined in ways to make allowance for heaving and settling, and a series of drainage ditches were dug beneath the building to carry off surface water.

Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of earlier structures and camping areas of the visiting Indigenous peoples. However, the extreme climate and the encroaching river are relentlessly destroying the entire site.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom