Music on the Home Front

Between 1914 and 1918, thousands of songs were composed in Canada. Although some of these songs were unrelated to the war, many encouraged enlistment, patriotism and support for the British Empire. Composers and publishers included messages that they believed would be popular among their wartime audiences. These songs were written by both professional and amateur musicians. While some were produced for commercial gain, others were published as fundraisers for the war effort. Although the Canadian government was not involved in producing these songs, they were played at recruitment rallies, parades and other wartime events (see also Patriotic Songs; Political Songs).

People listened to music differently then: while wealthier households had phonographs or gramophones (early record players), many middle-class families bought sheet music, which they played on their pianos at home. Songs were also performed at music halls. (See also Songwriters and Songwriting [English Canada] Before 1921.)

Patriotic Propaganda

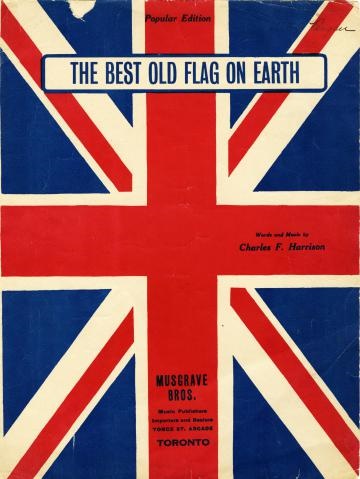

From the early years of the war, many popular songs emphasized the historic relationship between Britain and Canada to inspire support for “king and country.” The patriotic messages in this group of upbeat marching songs were commonly used as propaganda during recruitment rallies, parades and other wartime activities with the aim of encouraging enlistment. The lyrics reference British symbols, such as the Union Jack, which often appeared on the sheet music covers.

One of the earliest songs on the theme of supporting the British Empire is “The Best Old Flag on Earth,” composed by Charles F. Harrison in 1914. The cover page is decorated with the Union Jack in bright colours. The song supports the idea that the countries of the British Empire should stand by the British and fight for “the old Union Jack, the best old flag of all.” Although the song mentions fighting “For the maple leaf/Our emblem dear” and includes the tune of “The Maple Leaf Forever,” it is clear that, in the end, Canada would fight on behalf of Britain. Similar themes appear in Gordon V. Thompson’s “Heroes of the Flag” (1917) and “For the Glory of the Grand Old Flag” (1918), as well as in Michael F. Kelly and Albert E. MacNutt’s “We’ll Never Let the Old Flag Fall” (1915). (See also Flag Songs.)

Morris Manley’s “Good Luck to the Boys of the Allies,” composed in 1915, was one of the most successful patriotic songs produced during the war. This marching song encourages those on the home front to support enlistment and offers “good luck to Johnnie Cannuck/And all the Allie [sic] soldiers.” The song also emphasizes a duty to Britain while fighting for the Union Jack. A distinguishing feature is the inclusion of the melody of “God Save the King” (see also National and Royal Anthems). Clearly, composers and publishers believed that stressing imperial ties would be a motivating force for enlistment and support of the war in Canada.

Canadian Identity

The First World War also contributed to a sense of national identity. Music was used to promote common values among English Canadians, in particular. Composers referenced Canada’s vast landscape in popular songs to emphasize Canadian unity in wartime. “Johnnie Canuck’s the Boy,” composed by Jean Munro Mulloy in 1915, acknowledges the widespread call to action across Canada: “From where the Rocky Mountains dip/And virgin Prairies sweep/From Arctic rim to Scotia’s tip/Our call is o’er the deep.”

Many wartime songs also included references to maple trees and the maple leaf, which had been a Canadian emblem since the 19th century, long before the adoption of the current flag in 1965. Alexander Muir’s “The Maple Leaf Forever” was the de facto national anthem among English Canadians by the late 1800s. The maple leaf often appeared on sheet music covers, such as “Boys from Canada,” composed by Alberta-Lind Cook in 1915. This song also discusses the maple leaf in the lyrics, referring to the maple leaf insignia on the soldier’s uniforms and declaring Canada to be “The Country of the Maple.”

One of the clearest expressions of Canadian national identity is “I Love You Canada,” composed by Morris Manley and Kenneth McInnis in 1915. The sheet music cover features a colourful map of Canada. This song was very successful and was ideal for sing-alongs, as the melody was simple and within the average person’s vocal range. Unlike many other wartime songs, “I Love You Canada” didn’t include any British imperial symbols or references. Similarly, Will J. White’s “The Hearts of the World Love Canada” (1918) is unabashedly patriotic: “Where oh!/Where are the men of Canada?/Where are those who have gone away?/They are trenching on fields of Flanders/Bringing honour to us today.”

Gender Roles and Expectations

Many of the popular songs composed in Canada during the First World War expressed gendered notions of war. The songs’ lyrics consider the masculine duty of becoming a soldier, as well as the roles and expectations of women in wartime, with cover art that depicts these gendered images.

Many wartime songs explicitly linked military service with “masculine” traits such as bravery, pride and loyalty. This can be seen in the song “Soldier Lad,” composed by W.H. Stringer and Charles W. Lorriman in 1914. The chorus was written from the perspective of a soldier’s sweetheart, who praises him for supporting the war and awaits his return: “Soldier lad I’m proud you’re leaving/...I shall yearn for your returning/You’re so brave my soldier lad.” Another song that describes the masculine soldier is “Khaki,” composed by Gordon V. Thompson in 1915: “And the man who’s dressed in khaki/Is a man we’re proud to know!/For he fights to guard the Empire/Our gallant soldier lad!”

Other popular songs evoked gendered wartime roles for Canadian women, such as encouraging men to enlist and remaining strong while men were away at war. The song “I’ll Come Back to You When My Fighting Days Are Through,” composed by Frank O. Madden in 1916, encourages women to “smile and be brave while I’m gone.” Some wartime songs, like Morris Manley’s “Goodbye Girls” (1918), highlight the role of women as nurses: “Please come and help the cause/You are wanted every day/We need the girls as well as men/This war it must be won/It’s up to one and all to help the man behind the gun.”

One particular song is notable for challenging gender expectations with the title question “Why Can’t a Girl Be a Soldier?” This song, composed by Lindsay E. Perrin, considers the contribution that women could make as soldiers because they can “carry a gun good as any mother’s son.” Although the song is unique in suggesting that women could be soldiers, it does reflect the commitment of women, as well as men, to the war effort. (Interestingly, this song was likely adapted from an American song of the same name, published by Roger Halle in 1906.)

Sentimental Songs

Sentimental songs expressed a longing for a reunion between soldiers and their families and lamented Canadian deaths. These songs take different perspectives, from soldiers serving overseas to mothers and children on the home front. Due to their storytelling nature and sombre tone, sentimental songs were composed as ballads and waltzes.

Many sentimental songs were written from the perspective of a soldier thinking about his pre-war days and loved ones left behind in Canada. In the song “Home Again,” composed by Will J. White and Jules Brazil in 1917, a soldier explains that he and his comrades thought of home and sang “the songs that bring back memories.”

Other songs recognized the concerns of mothers on the home front. In the song “When Your Boy Comes Back to You,” composed by Gordon V. Thompson in 1916, the mother is encouraged to “Cheer up! Don’t be blue!” while waiting for her son to return. The song’s message offered hope to mothers on the Canadian home front by continually emphasizing the line “Till your boy comes back to you!” The cover of the sheet music further reinforces this sense of hope with an image of a soldier returning home to his mother, meeting her at “the old garden gate” as promised.

The voice of a child longing for the return of his or her father was also common in sentimental wartime songs. One of Morris Manley’s most popular songs from 1916, “I Want My Daddy,” was often sung by his young daughter, Mildred Manley, pictured on the sheet music cover along with her father. The song tells the story of a young girl filled with sadness over her father’s absence due to the war. In the chorus, the girl cries, “I want my Daddy/I’m as lonely as can be/I want my dear old Dad/tho’ he’s far away from me.” The song’s emotional lyrics remind us of the war’s impact on Canadian children.

The grim reality, of course, was that many sons, husbands and fathers never returned. This, too, was reflected in songs written by Canadians during the war. Not long after John McCrae’s famous poem, “In Flanders Fields,” was published in 1915, composers began setting it to music (see In Flanders Fields Music): “We are the Dead. Short days ago/We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow/Loved and were loved, and now we lie/In Flanders fields.” The themes of death and loss are also central to J. Heward Gammond’s “Take Me Back to Old Ontario,” composed in 1915. The lyrics express a sense of despair and loneliness: “In a far and foreign land/Lay a wounded soldier boy/He was fighting for a flag he thought was right/And as he lay there dying his comrades gathered near…”

Significance

Music offers us another way of viewing — or hearing — the past. Composers and publishers created songs with their audience in mind, so the messages contained in the lyrics, music and cover art give us a better understanding of Canadian values and interests at the time. Importantly, these songs portray an idealized version of wartime Canada. The reality was more complicated. Some Canadians, including many francophones and minority groups, were unmoved by appeals to support the British Empire. As the war continued and losses mounted, Canadian men became more reluctant to volunteer (see Military Service Act). Gender roles and relations were also more contested than popular songs might suggest. Despite this, these wartime songs provide important insight into the views and attitudes of many Canadians. The songs reveal widespread support for the war effort in Canada, particularly among anglophones, even though they increasingly reflected the pain and sacrifice of war as the conflict wore on.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom