Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario, is the common name for both a reserve and a Haudenosaunee First Nation. The reserve, legally known as Six Nations Indian Reserve No. 40, is just over 182 km2, located along the Grand River in southwestern Ontario. As of 2019, Six Nations has 27,559 registered band members, 12,892 of whom live on-reserve. Six Nations is the largest First Nations reserve in Canada by population, and the second largest by size. There are several individual communities within the reserve, the largest of which is Ohsweken, with a population of approximately 1,500. (See also Reserves in Ontario.)

Six Nations is home to the six individual nations that form the Hodinöhsö:ni’ Confederacy (Haudenosaunee). These nations are the Kanyen’kehaka (Mohawk), Onyota’a:ka (Oneida), Onöñda’gega’ (Onondaga), Gayogohono (Cayuga), Onöndowága’ (Seneca) and Skaru:reh (Tuscarora).

Ayenwahtha Wampum Belt

The Ayenwahtha wampum belt documents the establishment of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. From right to left, the belt depicts the territory of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca. The Tuscarora became the Confederacy's sixth nation in 1722.

The community is occasionally represented by a flag depicting the Ayenwahtha wampum belt. The belt documents the establishment of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy by the Peacemaker. The first five nations to join the Confederacy are depicted in white, a colour of peace, over a background of purple, a colour of war. This acknowledges the conflict that predated their confederation. It also articulates how the concept of kanikonhri:yo (a good mind) can lead to peace and healing. This belt also serves as a map of the Haudenosaunee homelands, which are now part of upstate New York. From right to left, the map depicts the territory of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca. The central heart acknowledges the important role of the Onondaga in kindling the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Council Fire. The Tuscarora sought refuge with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in 1722, as a result of British colonial expansion into their homelands in the Carolinas. Later that year, they were accepted as the Confederacy’s sixth nation.

History

The territory that now forms the Six Nations reserve was formerly Haudenosaunee hunting grounds. This land was also formerly occupied by the Attiwonderonk (Neutral) nation. As a result of the American Revolution, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy relocated to this area in 1784. Much of the Confederacy aligned with the British during this conflict in order to fulfill treaty obligations, such as those in the Covenant Chain. They also wanted to defend their homelands from the encroachment of Americans. The British promised that after the revolution Haudenosaunee homelands would be secure. However, the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, ceded Haudenosaunee territory to the United States.

(courtesy Native Land Digital / Native-Land.ca)

As compensation for the loss of their homelands, Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) was able to secure a tract of land for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy from Sir Frederick Haldimand, the Governor of the Province of Quebec. The land consisted of six miles on either side of the Grand River from Lake Erie to the river’s head (north of present-day Elora). When surveyed in 1821, the land grant was about 2,740 km2. Subsequent representatives of the Crown, such as John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, reinterpreted the grant as land that was reserved for the Confederacy, but not legally owned by them. This shift in policy later benefited non-Indigenous squatters and prospectors when they claimed portions of the land grant to develop homesteads or communities.

The territory under Six Nations jurisdiction shrunk over the next century. This occurred as a result of long-term leases facilitated through the Confederacy Council, sales negotiated by individuals such as Joseph Brant, or as a result of agreements made by representatives of the Crown. The final reduction of territory occurred in 1847, leaving only 5 per cent of the original Haldimand Proclamation lands, representing the current reserve boundaries.

That same year, the Credit River Band of the Mississaugas approached the Six Nations Confederacy Council. The Mississaugas needed a place to live after ceding nearly all of their territory near Lake Ontario. They were granted primary use of 19 km2 in the southeastern portion of the Six Nations reserve, now legally known as New Credit Indian Reserve No. 40A.

Governance

Six Nations of the Grand River retained their Confederacy Council governance system into the early 20th century. In this system, women assigned the role of chief to selected men, who then governed through a consensus decision-making model.

Federal government officials such as Duncan Campbell Scott, the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, were unhappy with Six Nations’ method of governance. They wanted Six Nations to transition to an elected governance system that mirrored Canadian municipalities. Scott and the federal government were often in conflict with the Confederacy Council, as the federal government thought that they were in control of the territory, while the Six Nations viewed themselves as a sovereign nation.

Throughout the 1920s, the Confederacy Council presented their case for sovereignty to the House of Commons and the Supreme Court of Canada. These claims were based on the fact that the Haudenosaunee had never agreed to be subjects of the Crown. When these arguments were not heard by the Government of Canada, the Confederacy delegated Deskaheh (Levi General) to take their argument directly to the Crown and League of Nations. Deskaheh was a council speaker and Cayuga Bear Clan chief.

Deskaheh’s tactics made Duncan Campbell Scott angry. In 1924, he had an order-in-council approved allowing the RCMP to officially remove the Confederacy Council from the Council House on the Six Nations reserve. Shortly after, Scott and the local Indian Agent, Colonel C.E. Morgan, facilitated the election of the reserve’s first elected council. While the elected council is now recognized by the Government of Canada under the Indian Act, both councils remain in place today.

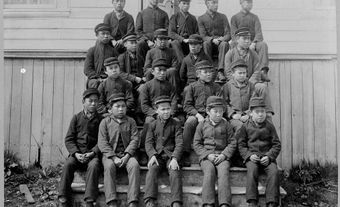

Mohawk Institute Residential School

The Mohawk Institute opened in 1828 and closed in 1970, making it the longest running residential school in Canada. Children from Six Nations, as well as other First Nation communities, attended the school.

The Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School, located in Brantford, Ontario, was the longest running residential school in Canada. Founded in 1828 as the Mechanics’ Institute, a day school for boys from Six Nations of the Grand River, the institute began accepting girls in 1834. The school was operated by the Anglican Church of Canada until 1969, when the federal government took over. This school also had students from as far as Sarnia, Ontario and Kahnawake, Quebec. Students of the Mohawk Institute attended the nearby Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks, built in 1785. Today, the chapel is the oldest surviving church in Ontario.

In 1972, the Woodland Cultural Centre was established at the site of the former residential school, under the direction of the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians. The cultural centre is now supported by the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, Six Nations of the Grand River, and the Wahta Mohawks. Among other activities, the Woodland Cultural Centre is working to restore the Mohawk Institute so that the school might serve as a physical reminder of the Government of Canada’s assimilative initiatives.

Culture

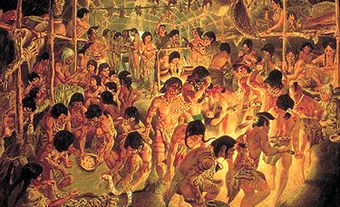

Six Nations hosts the Grand River Champion of Champions Powwow every July.

Six Nations has been home to many well-known figures. These include poet Tekahionwake (E. Pauline Johnson), Boston Marathon winner Tom Longboat, actor Jay Silverheels (The Lone Ranger) and Academy Award nominee Graham Greene (Dances with Wolves). Six Nations hosts the annual, internationally recognized Grand River Champion of Champions Powwow. The powwow is held on Chiefswood, the former estate of E. Pauline Johnson. Chiefswood was recognized as a National Historic Site of Canada in 1953. Members of Six Nations have also played for the internationally recognized lacrosse team the Iroquois Nationals. Playing as a sovereign nation, the Nationals have occasionally travelled to tournaments using Haudenosaunee passports.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom