Specific claims originate in First Nations’ grievances over outstanding treaty obligations, or the administration of Indigenous lands and assets under the Indian Act. Specific claims have been dealt with by several mechanisms since 1973. The Specific Claims Tribunal — an independent judicial body created by the federal government in 2009 — has the authority to make final and binding decisions.

Historical Background to Specific Claims

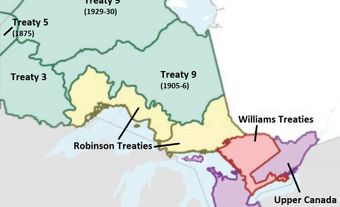

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 dictated that only the British Crown could negotiate treaties with Indigenous peoples for the purchase of Indigenous lands in Canada. The British government and, after 1867, the Canadian government, concluded treaties with various Indigenous groups in order to legitimate European settlement in their lands.

The settlement of Canada by immigrants over time made the original inhabitants of this land a minority within an expanding agricultural and industrial economy. In some cases, bands that had signed treaties lost control of their lands through the illegal (under the Indian Act) sale or lease of reserve lands, or through the fraudulent activities of Department of Indian Affairs’ employees in selling or leasing reserve lands. In other cases, land promised by treaties was never allocated. In still other cases, communities received inadequate compensation for the sale or damage of reserve lands.

Indigenous peoples on isolated reserves had little means to make a living after traditional subsistence methods had been outlawed or made impossible. These conditions were worsened by the government’s failure to live up to treaty and other legal obligations to distribute reserve lands and protect these lands from encroachment, to provide aid in transitioning to an agricultural economy, and to safeguard First Nations’ funds and other assets.

Specific claims originate in grievances over outstanding treaty obligations or the administration of lands and assets under the Indian Act.

Process of Negotiating Specific Claims: 1973 to 2007

Some communities had pressed their claims beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, from 1927 to 1951, the Indian Act prohibited the use of band funds to sue the federal government. First Nations’ claims that Canada had not fulfilled its obligations under treaties and the Indian Act, therefore, were largely ignored.

In 1947, a Senate/House of Commons joint committee recommended the establishment of a “claims commission” to “inquire into the terms of all Indian treaties… and to appraise and settle in a just and equitable manner any claims or grievances arising thereunder.” A 1959–61 joint committee also recommended that an Indian claims commission be appointed to investigate land grievances in British Columbia and in Oka, Quebec. A 1969 bill made the same suggestions, but a commission was not put into place.

In 1973, the Calder Case opened up the possibility for legal acknowledgement that Aboriginal title to land had persisted despite European settlement. This prompted a review by the federal government about how Indigenous land claims were being addressed. In a new process, the Office of Native Claims (ONC), formed in 1974 within the federal government, distinguished two types of claims: those based on the argument that Aboriginal title had never been extinguished in areas of Canada not covered by historic treaties, i.e., much of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, eastern Canada, Quebec and British Columbia (comprehensive claims); and those stemming from accusations that the federal government had failed to live up to its legal obligations under treaties and other legislation (specific claims).

Indigenous groups consistently criticized the conflict of interest inherent in a department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada(INAC) — the Office of Native Claims — evaluating and negotiating claims against it. By 1981, only 12 of the approximately 250 specific claims submitted to the government had been settled. The 1983 Penner Report on Indian Self-Government recommended that the ONC’s negotiation model be replaced with an independent body. After the flare up of disputes in Oka that began in the summer of 1990, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced the creation of a joint Assembly of First Nations and INAC working group to develop an independent claims negotiation process. As well, Mulroney announced the formation of the Indian Specific Claims Commission (also called the Indian Claims Commission, or ICC), a temporary independent advisory body that would review specific claims rejected by the government.

From 1991 to 2009, the six commissioners of the ICC investigated specific claims that the government had declined to accept for negotiation. The ICC, however, was only able to pass non-binding recommendations about how claims should be settled; in other words, its judgements could effectively be ignored by the Government of Canada. Throughout its years of operation, the ICC’s annual reports called for the creation of a new independent body that would have the authority to make decisions on claims that both parties would be bound to accept.

The final report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, issued in 1996, made a similar recommendation that an independent tribunal be appointed to facilitate negotiations between Canada and Indigenous groups on land issues and historic claims. An attempt to form such a tribunal in the early 2000s, however, floundered.

The Specific Claims Tribunal: 2007 to Present

On 12 June 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Assembly of First Nations’ National Chief Phil Fontaine announced the reform of the specific claims system and the creation of a tribunal staffed with impartial judges who had the authority to make final and binding decisions and to award compensation. Bill C-30, the Specific Claims Tribunal Act (SCTA), received royal assent in June 2008.

The Specific Claims Tribunal opened late in 2009. Specific claims are still received first by the claims department of Indigenous affairs, now known as Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, which has three years to assess the claim and decide whether or not to accept it for negotiation. If the claim is accepted by negotiations, the government then has three more years to reach a settlement. If the claim does not reach a settlement within that time frame, a First Nation can file the claim with the independent Specific Claims Tribunal. Alternatively, if the claim is rejected for negotiation within the initial three-year period, the claim can be filed with the Tribunal.

The federal government provides funding for the research and presentation of specific claims. These are loans that must be repaid from the proceeds of the eventual settlements.

At the Specific Claims Tribunal, claims rejected by the government are heard by justices, often in the originating community. The Tribunal has the ability to award financial compensation to a maximum of $150 million.

In his annual report dated September 2014, Justice Harry A. Slade warned that the Tribunal “has neither a sufficient number of members to address its present or future case load in a timely matter, if at all.” The Tribunal has already made decisions with important ramifications for the future of land negotiations in Canada (for example, the claim of Kitselas First Nation in British Columbia). It remains to be seen whether the Specific Claims Tribunal will fulfill its mandate of expediting final settlements and clearing the decades-long backlog of claims.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom