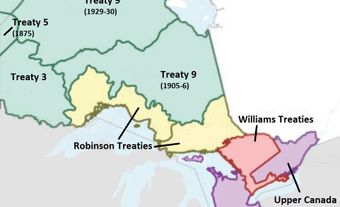

The St. Joseph’s Island Treaty of 1798 (also known as Treaty 11 in the Upper Canada numbering system) was an early land agreement between First Nations and British authorities in Upper Canada (later Ontario). It was one of a series of Upper Canada Land Surrenders. The St. Joseph’s Island Treaty encompassed all of St. Joseph’s Island, known as Payentanassin in Anishinaabemowin and today called St. Joseph Island. The 370 km2 island is situated at the northern end of Lake Huron, in the channel between Lakes Huron and Superior. The British needed a post in the area to protect their interests and maintain contact with Indigenous peoples of the region. The British also realized they would have to evacuate their post at Michilimackinac under the terms of Jay’s Treaty and needed an alternative location.

Historical Context

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the American Revolution, also established the new border between the United States and Britain’s remaining colonies in North America. Part of the new boundary ran through the centres of Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron and Superior. Before signing this treaty, Britain never consulted the many Indigenous peoples in the area, nor were they involved in the negotiations for the treaty. Under the terms of the treaty, the British also gave the United States much of the land they had earlier set aside for Indigenous use, as stipulated in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and subsequent treaties. Britain’s loyal Indigenous allies were stunned by what they saw as a clear betrayal of their interests.

Although the new international border ran through four of the five Great Lakes, the British maintained their western frontier posts on the American side of the line for several years after the Treaty of Paris. This included such locations as Oswego, Niagara, Detroit and Michilimackinac. The British retention of these posts angered the Americans, but they were afraid of another war with Britain. The Americans decided to orchestrate British evacuation of these posts through diplomatic means.

Jay’s Treaty was the result of diplomacy, rather than conflict, to resolve several outstanding issues from the war. Under the terms of the treaty, which was ratified in 1795, Britain agreed to evacuate its western posts by 1 June 1796. But even before Jay’s Treaty was ratified, it was obvious by the fall of 1794 that Britain would eventually give up these posts to the Americans. In anticipation, the British government advised Governor-in-Chief Lord Dorchester to prepare for the construction of new posts in British territory. Such posts would ensure the continuation of the fur trade with the region’s Indigenous peoples.

Meanwhile, Upper Canada’s first lieutenant-governor, John Graves Simcoe, wanted to obtain land on Georgian Bay, at present-day Penetanguishene, to offset the loss of Michilimackinac. Simcoe visited the location in 1793 and had it surveyed as a possible location for a naval yard. Based on the surveyor’s report, Simcoe commenced negotiations for the surrender of Penetanguishene harbour with the Anishinaabeg of the region.

Dorchester had other ideas, however, and did not agree with maintaining garrisons in the west. He believed in conserving his limited resources and keeping any posts closer to the country’s important centres of Montreal and Quebec. As a result, he did not authorize a post on Lake Huron for another 18 months. In April 1796, he ordered the commander at Michilimackinac, Major Doyle, to send a garrison to St. Joseph’s Island, rather than to Simcoe’s preferred location at Penetanguishene at the other end of Lake Huron. Dorchester had decided a 12-man garrison on the island would serve as a new rendezvous point for the Anishinaabeg of the area to replace Michilimackinac. Dorchester’s direction surprised most people, as it had not been considered by others involved in the process. It also annoyed Simcoe, as it nullified his efforts in establishing a post at Penetanguishene.

Negotiations and Outcome

In early June 1796, Lieutenant Andrew Foster led a small group to St. Joseph’s Island to establish a British post. Although the island was in Anishinaabe territory, it was unoccupied. Once Foster established the post, representatives of the Indian Department also moved there. Shortly afterward, local Anishinaabeg began to visit the post and ask about payment for the island. They were still unhappy with the British over the evacuation of Michilimackinac and with Jay’s Treaty. As far as they were concerned, these were yet more examples of British abandonment.

By now, Ensign Leonard Brown was in command. He and his men were vulnerable: the garrison was tiny, a fort had yet to be built, they were far away from British assistance and surrounded by angry First Nations. To placate them, in the summer of 1796, Brown proposed a formal council be held that fall, with a proper ceremony and distribution of goods. But Dorchester’s direction entered the picture once again, this time to hinder Brown. In December 1794, the governor-in-chief had decreed that any proposed purchases would have to be approved by the governor-in-chief and contain a sketch of the area to be bought. Authorities would then decide the amount to be paid for the land.

Deputy Superintendent General and Deputy Inspector General of Indian Affairs Colonel Alexander McKee arrived in 1797 and negotiated the terms of the treaty with the Anishinaabeg for the sale of the island. He returned the next year with the goods required to complete the sale. At a formal council on 30 June 1798, McKee and seven principal chiefs signed the treaty. For 1,200 pounds worth of goods, the Anishinaabeg relinquished their claim to St. Joseph Island. The merchandise included various kinds of cloth, along with thread and ribbon, 680 blankets, 55 hats, 24 dozen pipes, 21 dozen combs, 15 dozen mirrors, 15 dozen scissors, five dozen fire steels, 4,000 flints, 15 guns, 10 rifles, 400 lbs. of gunpowder, 20 dozen ball and shot, 42 dozen knives, 300 lbs. of tobacco, and various cooking implements. As was the custom after signing treaties, the Commissary Department furnished a bullock and 50 gallons of rum for a celebratory feast.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom