Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow was a document that set out land claim grievances in Yukon and recommended an approach to settlement. The Council of Yukon Indians, the organization that authored the document, presented it to then Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau in Ottawa on 14 February 1973. The document told the story of traditional Indigenous ways in the territory. It chronicles ways in which life changed with the arrival of the “Whiteman.” It identifies some of the contemporary challenges the local First Nations faced at the time. Additionally, it proposes solutions and offers a roadmap forward. Finally, it sets out a vision for the future that sees control and authority for decision-making returned to the First Nations of the territory. Fifty years later, it continues to be a guiding force for First Nation and non-First Nation Yukoners. It promotes “walking together down the same road.” In other words, it suggests participating equitably as partners in the fabric and governance of Yukon society.

Treaty History in Yukon

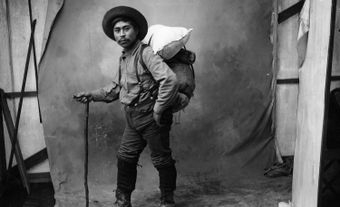

Unlike the situation in most of Southern Canada, prior to 1993 there were no treaties in Yukon. The first steps towards Yukon First Nations land claim settlements were taken in 1902. At that point, Ta'an Kwäch'än Chief Jim Boss (Kishxóot) wrote to the Yukon Commissioner and the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs. He requested compensation for his people’s loss of land and hunting grounds following the influx of people into the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush. Specifically, Chief Boss petitioned the Commissioner of Yukon for a 1,600-acre reserve. The petition contained the famous quote: “Tell the King very hard we want something for our Indians, because they take our land and our game.” Unfortunately, the federal government denied Chief Boss’s request. However, it would be used in the future to affirm and maintain Indigenous rights in Yukon.

The Indian Act and the Yukon

The initial request and denial for a treaty led to an effort to organize First Nations in the territory in the mid-1960s. In 1951, the federal government repealed some of the more punitive elements of the Indian Act. The 1951 amendments meant it was now legal for Yukon First Nations to practise their culture. The potlatch (which is very important in Yukon) was no longer banned. Additionally, lawyers could now be hired to sue for Indigenous rights. Just prior to these changes, many Indigenous soldiers returned from the Second World War. They discovered they were enfranchised and had lost their official status as Indians. A veteran of the Second World War, Elijah Smith came from the small Yukon First Nation community of Champagne. Returning to Yukon after the war, Smith realized he was viewed as equal on the battlefield but not at home. A southern Tutchone (pronounced two-shown-ee) man, he was an important leader in the self-government movement. He was also the architect of the Yukon land claims. In 1968, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (see Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs) sponsored a meeting in Whitehorse regarding proposed changes to the Indian Act. Smith spoke at these hearings, saying:

We, the Indians of the Yukon, object to… being treated like squatters in our own country. We accepted the white man in this country, fed him… helped him to find the gold; helped him build and respect him in his own rights. For this we have received little in return. We… would like the government of Canada to see that we get a fair settlement for the use of the land. There was no treaty signed in this Country, and they tell me the land still belongs to the Indians.

At this time, many Yukon First Nations women were also being stripped of their status. Under the terms of the Indian Act, Indigenous women lost status for marrying a non-status person. They were also denied their rights in favour of a patriarchal society. Although most Yukon First Nations followed a matrilineal clan system, there are many stories of federal agents going into communities and insisting to speak with male chiefs and purposefully ignoring the women. This undermined traditional, local governance protocols.

In 1960, First Nations people were granted the right to vote across Canada. Also, in the 1960s and 1970s, important legal and judicial decisions and political proposals ensued. A prominent court case was the Calder Case, which set the stage for the modern treaty policy and process.

Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow

Movement for a modern treaty gained momentum when the Yukon Native Brotherhood was formed in 1968, led by Elijah Smith. The Yukon Native Brotherhood was followed by the creation of the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians. Around this same time, in Alaska, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was being negotiated and finalized. A delegation of Yukon First Nations, led by Smith, went to Ottawa. They presented Together Today for our Children Tomorrow: A Statement of Grievances and an Approach to Settlement by the Yukon Indian People to then Canadian prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau on 14 February 1973. This ground breaking document detailed both the problems Yukon First Nations identified, as well as a plan for addressing them. Together Today for our Children Tomorrow was among the first land claim proposals to be accepted by the Government of Canada under its new comprehensive land claims policy, and the negotiation of modern treaties in Yukon began shortly thereafter. In 1993, the Council for Yukon Indians (now the Council of Yukon First Nations) and the government of Canada and Yukon signed the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA). The UFA served as the template for the signing, between 1993 and 2005, of self-government agreements (see Indigenous Self-Government in Canada) for 11 of the 14 Yukon First Nations (see also Self Governing First Nations in Yukon).

“This Settlement is for our children, and our children’s children, for many generations to come. All our programs and the guarantees we seek in our Settlement are to protect them from a repeat of today’s problems in the future. You cannot talk to us about the “bright new tomorrow”, when so many of our people are cold, hungry and unemployed. A “bright new tomorrow” is what we feel we can build when we get a fair and just Settlement. Such a Settlement must be made between people of peace. There must be a “will-to-peace” by all the people concerned. We feel we have shown this “will-to-peace” for the last hundred years. If you feel the same, it should be easy for us to agree on a Settlement that will be considered “fair and just” to all. If we are successful, then the date of our agreement will be a day for all to celebrate – in the years to come…. If we are successful, the day will come when ALL Yukoners, will be proud of our Heritage and Culture, and will respect our Indian identity. Only then will we be equal Canadian Brothers.”

- Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow

Modern Treaties

In many ways, Yukon has been a leader in modern treaty making. Since 1993, 11 of Yukon’s 14 First Nations have signed self-government agreements. As of 2023, there are 25 self-government agreements covering 43 communities. The 11 agreements were created from the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA). While the UFA is a political agreement that underpins the self-government agreements, it is not a legal document. It has 28 chapters containing common terms that apply to all Yukon First Nations with final agreements. Every Yukon First Nation has the right to negotiate “specific terms” for its final agreement, where permitted in the UFA. Yukon First Nations then ratify their own final agreements and self-government agreements in a manner determined by them. The First Nations that have agreements no longer fall under the purview of the Indian Act. The Yukon agreements fundamentally alter the underpinnings of Yukon society. They set out the understandings that guide intergovernmental relationships and have redefined existing relationships between First Nation and non-First Nation people.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom