The Ladies Ontario Hockey Association (LOHA) was the first governing body for community women’s ice hockey in Canada. It was formed in 1922 and disbanded in 1940. Initially, the league consisted of 18 senior teams from across Ontario, from bigger cities such as Toronto, London and Ottawa, to smaller centres such as Bowmanville, Huntsville and Owen Sound. The creation of the LOHA led to the 1925 founding of the Women’s Amateur Athletic Federation, which absorbed the LOHA when it disbanded.

Hilda Ranscombe is recognized by many as the best women’s hockey player in Canadian history. She was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2015.

Background

When the LOHA was formed in 1922, hockey was considered a game for boys and men. In the book Coast to Coast: Hockey in Canada to the Second World War, Carly Adams discusses the general societal attitudes at the time. “Historically, the attempts of girls and women to enter this ‘sacred’ territory [of hockey] have been viewed with derision. Through a complex process of control and compromise, women’s hockey was effectively stigmatized as an inferior form of the ‘real’ game,” and women had to constantly “fight for legitimacy” against their male counterparts.

However, progress was made with female participation in ice hockey around the time of the First World War. Many Canadian women at this time were in the workforce but still had time for recreation. (See also Women and Sport; Canadian Women and War; Wartime Home Front.)

Formation

The LOHA was organized on 16 December 1922 at a meeting at the Temple Building in Toronto. Participants elected officers for the 1922–23 season, developed rules, and created a subcommittee to administer the operation of the league. Frank Best was the president of the league in its first year. Four women then served as president from 1923 to 1940: Janet Allen (1923–27); Hazel Ruttier (1927–34); Canadian track and field star Bobbie Rosenfeld (1934–39); and Roxy Atkins (1939–40). It was important for the LOHA to have women in positions of executive power, with men in advisory roles.

Early Challenges

In 1923, the LOHA did not receive support from the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA). In a CAHA vote, players in the LOHA were not granted official recognition. The other challenges the LOHA faced included the belief that women’s hockey was incompatible with conventional standards of femininity, and the belief that hockey was too rough a sport for women to participate in.

A women's hockey team from Gore Bay, Manitoulin Island, Ontario, in 1921.

1920s

During its early years, the LOHA held its own financially. “Press reports indicated that each year the association maintained a reasonable amount of money in its coffers,” according to Adams.

Receiving acceptance from the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada (AAUC) was equally challenging. The AAUC’s chief women’s advisor, John DeGruchy, “favoured the cutting out of anything that would make the game too strenuous” for women, Adams has said. However, by 1925, the LOHA had helped create the Women’s Amateur Athletic Federation. That organization helped give women more control of female sports and gave more Canadian women an opportunity to participate.

Also in 1925, an intermediate division in the LOHA was formed. This gave women of lesser skill the opportunity to play hockey. However, it proved challenging for the LOHA to attract teams to the lower-ranked division because of limited advertising resources.

1930s

As with many Canadian organizations in the 1930s, the main challenge for the LOHA was simply to survive the Great Depression. LOHA funds were reallocated to essential services. Among the problems the LOHA faced were a decrease in both participation numbers and access to rinks, as men’s hockey teams in Ontario received priority ice time. (During this time, most rinks in Canada used natural ice surfaces and were dependant on seasonal variations.) In frustration, LOHA president Rosenfeld asked in her regular column for the Globe and Mail, “who said ladies first?” By 1934, only seven teams had membership, and there was only one team from Toronto. By 1937, the league returned to having only a senior division.

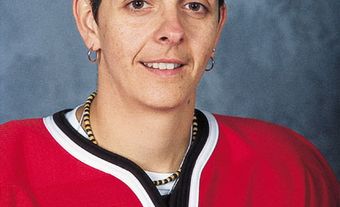

The Preston Rivulettes women's hockey team in the 1930s. Hilda Ranscombe is seated in the front row, first on the left.

Preston Rivulettes

In 1931, the Preston Rivulettes (who played in present-day Cambridge) joined the league and quickly became its most dominant team. The Rivulettes won all but five of the roughly 350 games they played, with three ties and only two losses. They won 10 Ontario titles and four Dominion championships. However, their domination and the attention it garnered were not considered entirely positive. Teams were reluctant to join the association because their chances of beating the Rivulettes were slim. (The Rivulettes were often compared to the Edmonton Grads women’s basketball team, who won 95 per cent of their games).

The Rivulettes’ top player was captain Hilda Ranscombe of Doon, Ontario. Recognized by many as the best women’s hockey player in Canadian history, Ranscombe was praised for her “dazzling speed and excellent stickhandling skills.” In 2015, she was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. The Canadian theatre production Glory, first produced in 2018, tells the story of the Rivulettes.

Disbandment

By the end of 1940, the LOHA had ceased operations. In the 1940s and 1950s, women’s hockey struggled due to the Second World War. Public interest in women’s hockey saw a resurgence in the 1960s and 1970s and has gained momentum ever since.

See also Women and Sport; The History of Canadian Women in Sport; Canadian Sports History; Ice Hockey in Canada; Origins of Ice Hockey.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom