For hundreds of years, very few sports were considered appropriate for women, whether for reasons of supposed physical frailty, or the alleged moral dangers of vigorous exercise. Since the late 19th century, however, women in Canada have participated in a growing list of sports — not only those deemed graceful and feminine, but also the sweaty, rough-and-tumble games traditionally played only by men (e.g., hockey, boxing, soccer, rugby)

Indigenous Women and Sport in the Pre-Colonial Era

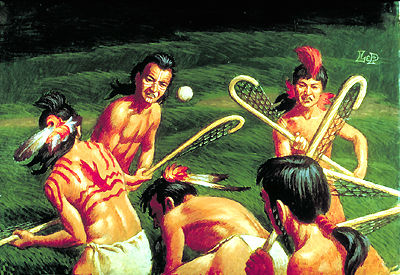

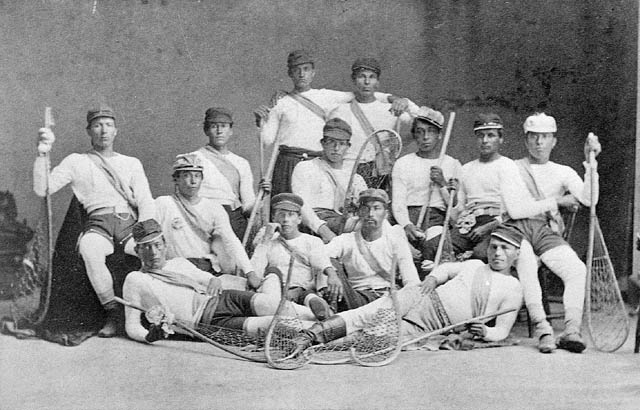

While historians know relatively little about the lives of Indigenous women in the pre-colonial period, it is likely that women participated in some games and contests, including the precursors of shinny, lacrosse, and football. In many First Nations, the games were reserved for men only, but in others, certain games were played by women alone, or by both sexes. Shinny, a game which is similar to hockey, was often considered a women’s game. Players would use a curved stick to hit a small round ball made of wood or stuffed buckskin along the ground or ice. Double ball, a more difficult and faster game than shinny, was primarily a women’s game in which they used long sticks to toss two balls that were tied together with a thong. Indigenous women played some football-like games in the pre-colonial period as well; when they played these games with men, they were often allowed to throw the ball (whereas the men were required to kick it). While baggataway and tewaarathon, the precursors of lacrosse, were generally considered to be for men, women were sometimes allowed to play. However, European colonization would restrict the opportunities for Indigenous women, as they were increasingly confined to small settlements and subjected to European ideas about appropriate female behaviour.

Women and Sport in the Colonial Period

With the arrival of European colonists came new pastimes and games, and different ideas about the place of women in sport and society. French and British traders, military men, and colonists brought new sports to the area, but these were mostly reserved for men. Women had little opportunity to engage in these sports, and the few recreational activities considered acceptable for women were usually restricted to members of the (white) upper classes. In New France in the mid-17th century, upper-class women were encouraged to go horseback riding (sidesaddle) as it was considered healthy. Similarly, they could travel by sleigh (or carriole) in winter and horse carriage in summer. In the larger centres, dancing schools taught young women popular dances of the time, including minuets, hornpipes, cotillions, and country dances.

Colonial society — and the sporting world — changed significantly after the British conquered New France in 1763 and established British military garrisons in Québec and Montréal, as well as in Halifax, Saint John, Fredericton, York (now Toronto), Kingston, and Niagara. Along with a different language and culture, British military officers and landowners brought new sports to the area, including cricket, horse racing, fox hunting, and regattas. However, these activities were reserved almost exclusively for men.

For Indigenous women, the growing power of white settlers and governments meant fewer opportunities to participate in games and sports. In western Canada, fur traders married Indigenous and mixed-race women, and encouraged their daughters to adopt European ways and behaviours. Indigenous communities across North America were increasingly restricted to settlements, and were subject to new laws and regulations, as well as a European worldview which was largely hostile to Indigenous culture, beliefs and practices. Women in particular were affected by the imposition of European ideas, their status and autonomy undermined by patriarchal views about women’s place in society. Indigenous women lost not only power and position, but also the opportunity to participate in (traditional or European) games and sports.

Women and Sport in the Victorian Age

For much of the Victorian era women had very few opportunities in the world of sport. As the 19th century progressed, men’s athletic clubs flourished (particularly in Toronto and Montreal). As more and more men participated in sports, new “national” sports associations formed, and there were increasing attempts to standardize rules and to schedule regular competitions and leagues. However, these clubs were almost exclusively for men. As M. Ann Hall states in The Girl and the Game (2002), women were “[r]estricted by voluminous skirts and Victorian ideas about their physical and mental frailty, [and] were never welcome at these clubs” (Hall, 7). While the Montreal Ladies Archery Club was formed in 1858, there were few women’s sporting clubs in the 19th century.

While women were excluded from many sporting activities, there were some recreational opportunities for those women who had both time and money. In the winter, Victorian women in Canada participated in sleigh and toboggan parties, snowshoeing, iceboating, and skating (including fancy skating, the forerunner of figure skating). In the summer, they enjoyed picnics, croquet, boating, fishing, horseback riding, and even fox hunting. Some women tried roller skating or “parlour” skating on hockey rinks, which were covered with wooden floors for the summer season.

While there was little scope for women’s athletic competition, a few individual women competed in events such as walking matches (or pedestrianism), which were popular in the 1870s. At one such match, in 1879, two female contestants walked 25 miles (40 km) around a narrow track in a small hall in Montréal; the winner, Miss Jessie Anderson, completed the distance in 5 hours and 21 minutes. Women could also compete at the popular water regattas, many of which held girls’ and women’s events. This included the occasional canoe race for Indigenous women, who had even fewer athletic opportunities than most other women did in this period. Government legislation, particularly the Indian Act, restricted traditional pastimes and ceremonies, and encouraged the adoption of Euro-Canadian sports among Indigenous men; women were likely excluded from these games, given Victorian ideas about women and sport.

Bicycles, Bloomers, and the New Woman

Women gained a new freedom and expanded athletic opportunities with the advent of the new “safety” bicycle in the 1880s. The earliest bicycles, such as the penny-farthing (also known as the “ordinary” or high-wheel bicycle), were both dangerous and uncomfortable to ride. Heavy machines with two wheels of different size, they were difficult to mount and ride (especially for women, who had to contend with voluminous Victorian skirts), and their hard wheels made any bicycle journey decidedly uncomfortable. A few select women, including Montreal’s Louise Armaindo, competed on penny-farthing bicycles in the last decades of the 19th century. Armaindo started out as a strongwoman and trapeze artist, then turned to pedestrianism (walking races) before she started competing on high-wheel bicycles in 1881, mostly in the United States. She was among the few women who rode the penny-farthing or high-wheel bicycles.

However, in the 1880s, smaller, lighter bicycles were developed; these new bikes had equal-size wheels and pneumatic tires, and were powered by a sprocket and chain. The new “safety” bicycles made riding much safer and more comfortable, and they quickly became popular among both men and women. At a cost of from $50 to $110, many well-off women bought the bikes soon after they became available; moreover, as bicycles were considerably less expensive than owning and maintaining a horse, they were accessible to a growing number of women. As more and more men and women started cycling, new (social) cycle clubs proliferated. Many of these clubs, such as the Knickerbocker Club in Toronto, were open to both men and women; by 1895, there were around 10,000 “wheelmen and wheelwomen” in Toronto alone. Women also formed their own separate bicycle clubs, such as the Tam O’Shanter Club in Winnipeg.

For women, bicycles provided exercise, entertainment, transportation, and freedom. The bicycle also led to much-needed dress reform. While it was possible to bike in long skirts, many women adopted shorter styles for riding, including the split skirt and the controversial “bloomer.” While some Canadian doctors encouraged moderate cycling for women, arguing that it was healthy exercise and that it promoted the adoption of less restrictive clothing, others were concerned that cycling would cause damage to the uterus, or would produce a female orgasm. Women themselves were divided on the benefits and dangers of cycling; while many “New Women” enthusiastically embraced the freedom that bicycles provided, others warned that cycling was linked to moral decay, as women could ride without chaperones, and mingle with men at bicycle clubs.

While some doctors and suffragettes promoted cycling for its health benefits, the emphasis was on moderate physical activity. By the end of the 19th century, middle-class women were also encouraged to participate in sports such as horse riding, rowing, skating, badminton, lawn tennis, and golf — activities that were considered graceful, compared to team sports such as cricket, soccer, rugby, baseball, and lacrosse. In a 1890 article on “Modern, Mannish Maidens,” a (male) commentator lamented the interest of some women in playing lacrosse, and remarked that women were simply not made to run: “She can swim, she can dance, she can ride: all these she can do admirably and with ease herself. But to run, nature surely did not construct her” (quoted in Hall, The Girl and the Game, 21).

By the end of the 19th century, growing numbers of middle- and upper-class women were participating in sports such as tennis, golf, and curling, and were forming separate ladies’ sporting clubs. The first women’s tennis tournament in Canada was held in Montréal in 1881, and the first women’s Dominion tennis championship was held in Toronto the following year. In 1892, a ladies’ section of the Royal Montreal Golf Club was formed, and in 1894, women joined the Toronto Golf Club for the first time, soon making up about half the club membership. The first national women’s golf championship was played in 1901. In 1894, The Ladies’ Auxiliary Club of the Royal Montreal Curling Club was formed, becoming what was probably the first women’s curling club in the world. Women also became members of the Alpine Club of Canada, which, from its inception in 1906, welcomed female climbers and encouraged them to dress like men, wearing knickerbockers and sweaters. Phyllis Munday of Vancouver, a member of the ACC, was the first woman to ascend Mount Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies.

These women climbers, golfers, and curlers generally came from the middle class. Much less is known about the sporting pastimes of women from the lower classes, and even less about the opportunities for Indigenous women. From the 1880s to the late 1960s, many Indigenous girls were forced to attend residential schools, which were often located far from their families. Forbidden to play traditional games and pastimes, and denied the opportunity to participate in the Euro-Canadian sports taught to male students (sports like cricket, ice hockey, and soccer), Indigenous girls at residential schools had little access to physical recreation.

Women and Sports in the Early 20th Century

Although sports like tennis, golf, and curling were considered more acceptable for women than team sports, female athletes were also starting to play games such as hockey, softball, and basketball by the turn of the century. The first women’s ice hockey teams appeared in the early 1890s in Quebec, with clubs in Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Lachute, and Quebec City. However, the games were played infrequently and were quite informal. In general, there was little support for women’s team sports in most 19th-century communities. The drive for women’s team sports would come instead from the girls and young women who attended private schools, universities and colleges, and from the coaches and instructors who were determined to see them play. While no competitive sports were offered to girls in the public school system, private schools such as Bishop Strachan and Havergal College in Toronto emphasized sports and games for their female students. At Havergal, for example, girls practiced gymnastics, tennis, basketball, cricket, ice hockey, golf, track, and swimming. At universities — which women had started attending in the 1870s and 1880s — women competed in fencing, tennis, paper chase (the forerunner of cross-country races), ice hockey, field hockey, and basketball.

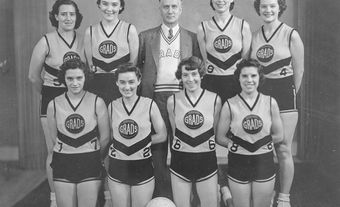

Basketball, which had been invented by Canadian James Naismith in 1891, was the most popular women’s team sport in the early 20th century. For example, by 1910 most towns in Nova Scotia had women’s basketball teams. In the 1920s and 1930s, a women’s basketball team from Edmonton dominated the sport. Known as the Edmonton Commercial Graduates (or the “Grads”), these women — most of whom were graduates of the McDougall Commercial High School — played across the country and internationally, winning over 90 per cent of their matches, and over 100 regional, national, international, and world titles. Their success inspired other Canadian women to take up the sport, and to participate in athletic activities more generally.

The most accomplished female athlete of the early 20th century (and perhaps of Canadian history) was Fanny “Bobbie” Rosenfeld, a Russian émigré who was nicknamed Bobbie because of her bobbed hair. The top-ranked female sprinter in Canada, she was also ranked number one in the long jump, shot put, and discus in 1925, and won Canada’s first Olympic medal (a silver) in women's track and field in 1928. Rosenfeld also won the Toronto Grass Court Tennis Championship, and played competitive basketball, softball, and hockey (her favourite sport). She was the star centre for the North Toronto AAA hockey club and captain of the Patterson Pats, dominating Ontario women’s hockey in the late 1920s. However, as in the Victorian period, there was considerable opposition to women’s participation in team sports such as hockey (which was, at the time, full contact and quite rough). Many commentators of the 1920s and 1930s believed that women should not participate in “sweaty” or “graceless” sports, but instead in what were considered graceful and feminine sports such as figure skating, diving, swimming, and tennis.

As in the Victorian period, Indigenous women were largely excluded from sports, whether team sports or those considered more graceful. One exception was softball, which many Indigenous women played, particularly those who lived on reserves or in Métis settlements. For example, the “Caledonia Indians” was a women’s softball team whose players mostly lived on the Six Nations reserve along the Grand River in Ontario. The team played exhibition games in southern Ontario, including in the Toronto leagues, and were semifinalists in the 1931 Provincial Women’s Softball Union championships. However, the “Caledonia Indians” were a rarity in the period.

Women’s Sports during the Second World War and the 1950s

During the Second World War, women entered the workforce in high numbers. As in the First World War, many of these women also participated in sports. Even though many men — including male athletes — had left to serve overseas, some games and tournaments continued, with women often taking the place of men on the playing field, as in the factories. These competitions were frequently used to support patriotic causes or to raise funds. Canadian women were also among the first to play professional sports: a total of 68 Canadians played in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, which operated between 1943 and 1954.

However, with the return of men after the war, women were encouraged to return to the home, and increased emphasis was put on women’s femininity and on traditional gender roles. This affected not only women’s opportunities in the workplace, but also in sports. Yet again, women were encouraged to participate in sports that emphasized beauty, grace, and contemporary concepts of femininity.

One such sport was figure skating, with Barbara Ann Scott a perfect example of the ideal female athlete of the time. A two-time world figure skating champion, and two-time European champion, Scott was Canada’s first Winter Olympic individual gold medallist, winning the gold medal at the 1948 Olympic Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Clearly an accomplished athlete, much of the media coverage emphasized her femininity rather than her athletic feats. A Time magazine feature from 1948 described her as follows: “Barbara Ann, with a peaches-and-cream complexion, saucer-size blue eyes and a rosebud mouth, is certainly pretty enough. Her light brown hair (golden now that she bleaches it) falls page-boy style on her shoulders. She weighs a trim, girlish 107 lbs … She looks, in fact, like a doll which is to be looked at but not touched.”

Based on the media coverage at the time, the idealized female athlete of the 1950s was therefore graceful and feminine; she was also preferably white. In this period, there was little room for female athletes of Indigenous descent. However, Indigenous women continued to play softball, such as Ruth Van Every (later Ruth Hill) who played for the Ohsweken Mohawks in the 1950s, and Toronto Carpetland — the Canadian champions — in 1964. Similarly, Phyllis “Yogi” Bomberry joined the Ohsweken Mohawks in the late 1950s, and in the 1960s joined Toronto Carpetland, who arranged a job for her at a communications factory in Toronto. Bomberry was named top batter in 1967 and all-star catcher in 1967 and 1968; both years her team won the national championship. However, despite the success of some Indigenous women in softball and fastball, they were largely absent from other sports at the time.

Feminism and Female Athletes in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s

Overall, the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s were years of enormous success for Canadian women in sports. The 1960s and 1970s witnessed the emergence of the “women’s liberation” movement in North America. Women increasingly fought restrictions in all areas of life, including sports. Plaintiffs brought sex-discrimination cases to court, arguing that girls should be allowed to play in games, and on teams, that were traditionally reserved for boys. In 1981, feminist athletes and activists established the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport (CAAWS).

Although there was little support for amateur athletes at this time, many Canadian women excelled at sports in this period. Prominent female Canadian athletes of the 1960s included swimmers Mary Stewart and Elaine Tanner, track athlete Abby Hoffman, and skiers Anne Heggtveit, Nancy Greene, and Elizabeth Greene. High-jumper Debbie Brill, the first North American woman to clear the six-foot barrier, dominated the sport in the 1970s. At the 1978 Commonwealth Games in Edmonton, Canadian women won gold in such sports as the pentathlon (Diane Jones Konihowski) and the discus (Carmen Ionescu), as well as in swimming and gymnastics. Indigenous twins Shirley and Sharon Firth, who had trained through the Territorial Experimental Ski Training program (TEST) in Inuvik, NWT, dominated cross-country skiing in Canada in the 1970s and 1980s. Black Canadian female athletes (many from the Caribbean) tore up the track in the 1970s and 1980s: Angela Bailey, Marita Payne, Jillian Richardson, Charmaine Crooks, and Molly Killingbeck. In 1984, Sylvie Bernier won Canada’s first Olympic gold medal in diving and Anne Ottenbrite became the first Canadian woman to win Olympic gold in swimming. In 1988, figure skater Elizabeth Manley won silver at the Olympic Winter Games in Calgary, and marathon swimmer Vicki Keith became the first person to swim all of the Great Lakes.

While sportswriters praised these (mostly young) athletes, some have noted that the tone of their reports could be patronizing and paternalistic. Take, for example, the case of teen tennis star Carling Bassett. Bassett was one of the most successful female tennis players in Canadian history, and was ranked as high as No. 8 on the Women’s Tennis Association tour. However, the media’s portrayal of Bassett focused on her looks, and portrayed her as a “daddy’s girl.” Indeed, a 1983 Sports Illustrated profile of Bassett was titled “Here’s Carling, her daddy’s darling.” Described in the 6,000-word profile as her father’s “favorite project,” much of the article focused on how Bassett felt about boys. As the result of pressure to look perfect, Bassett became bulimic in her mid-teens. This focus on female athletes’ looks was reflected in the media coverage of mature women athletes, which at times included references to their physical attractiveness and even sexual appeal.

h3>At the Top of Their Game: The 1990sCanadian women continued to excel in the 1990s. Colette Bourgonje, a Paralympic athlete, competed in her first Winter Games in 1990 in cross-country sit-ski. (Also a wheelchair racer, she would go on to compete in eight Summer and Winter Paralympic Games.) Rower Silken Laumann, who won a bronze medal at the 1984 Olympic Games with her sister Daniele in the double sculls, overcame a devastating leg injury to win Olympic bronze in the single sculls at the 1992 Olympic Summer Games (Laumann was also awarded the Bobbie Rosenfeld Trophy in 1991 and 1992). At the 1996 Olympic Summer Games, she won silver in the single sculls. Her teammates, rowers Marnie McBean and Kathleen Heddle, won two gold medals at the 1992 Olympics, and a gold and bronze medal in the 1996 Olympics, becoming the first Canadians to win three Olympic gold medals. In 1994, biathlete Myriam Bédard became the first Canadian to win two Winter Olympic gold medals. Two years later, track star Charmaine Crooks (who competed in five Olympic Games) became the first Canadian woman of colour to sit on the International Olympic Committee. Alison Sydor, winner of the 1996 Bobbie Rosenfeld Award, won a silver medal in mountain biking at the 1996 Olympics, and won three world championships in the sport (1994–6). At the 1998 Olympic Winter Games, Catriona Le May Doan won her first Olympic gold medal in speed skating (she would win again in 2002), part of a very successful women’s speed skating program which netted 18 Olympic medals from 1994 to 2010.

Canadian Women and Sport in the 21st Century

The sporting world of the 21st century looks very different to that of the Victorian period, or even the 1960s. Across the country, women are participating in high numbers in sports, including those traditionally seen as masculine or inappropriate for women. Young girls and women play rugby, soccer, and softball; like Carol Huynh and Tonya Verbeek, they wrestle, and some (like Mary Spencer) box competitively. Moreover, some female athletes have gained both female and male fans across the country. Take, for example, the national reaction to the victory of the Canadian women’s hockey team over the US team in the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, and in the 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2022 Games. Hockey players such as Angela James, Hayley Wickenheiser, and Geraldine Heaney have become famous. The 2010 Olympic feats of female athletes such as freestyle mogul skier Jennifer Heil, and bobsledders Kaillie Humphries and Heather Moyse, were celebrated across the entire country. Clara Hughes, OIympic speed skater and cyclist, is widely lauded for her sporting success as well as her activism, and the 2012 women’s Olympic soccer team became national celebrities, even after losing a heart-breaking semi-final match to the US team; in 2013, the team’s captain, Christine Sinclair, received a star on the Canadian Walk of Fame. The women’s soccer team took bronze again at the Rio Olympics in 2016, followed by a historic gold-medal victory at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021.

Although many women’s competitions are not televised on the major networks, interest in women’s sport has increased among both male and female spectators. A study conducted in October 2023 suggests that two-thirds of Canadians between 13 and 65 years of age are fans of women’s sport. In the survey of 2,000 Canadians, two in five regularly watched women’s elite sport and considered themselves “avid fans.” The first season of the Professional Women’s Hockey League (2024) broke attendance records for women’s hockey. The same year, Toronto was awarded the first Canadian franchise in the Women’s National Basketball Association – a league that has regularly attracted more than one million viewers per game in the 2024 season. A Canadian women’s professional soccer league, Northern Super League, will begin in 2025.

Sport and Sex

Despite the success of women in all types of sport, female athletes are still judged to some degree on their physical attractiveness. Although 21st-century sportswriters generally focus more on the athletic abilities and achievements of sportswomen than on their looks, marketing campaigns often use sex appeal to promote women’s sports. The International Volleyball Federation (FIVB) required female Beach Volleyball players to wear bikinis at all competitions until 2012. The women’s Lingerie Football League (later the Legends Football League) featured women wearing revealing uniforms; founded in the United States in 2009, it briefly included leagues in Canada and Australia. (The league cancelled the 2013 season in Canada due to concerns that the players from all four Canadian teams were not sufficiently prepared to play football.) While many female athletes are taken seriously in Canada, as across the world, the sexualization of women’s sports is another challenge facing athletic girls and women in the 21st century.

Another challenge facing female (and male) athletes is that of homophobia, which continues to persist in the world of sports. There has long been paranoia about lesbianism in women’s sports, and many female athletes and teams took pains to emphasize their heterosexuality and femininity in response to societal fears about “masculine” women athletes. In Higher Goals: Women’s Ice Hockey and the Politics of Gender (2000), Nancy Theberge argues that the strict emphasis on feminine dress and behaviour in the “Blades” (a competitive women’s hockey team) indicated a concern about mannishness and by extension, lesbianism, in women’s sport. In a 2013 article published in the Canadian Journal for Women in Coaching, Professor Guylaine Demers and researcher Bianka Viel argued that the sporting world could be a hostile environment for LGBTQ2S+ athletes. Few queer athletes felt comfortable revealing their sexuality while in active competition. According to a study released in 2020 by Monash University in Australia, many Canadian female athletes reported being victimized after coming out to their teammates. There are signs, however, that the Canadian sporting world is becoming more inclusive. In September 2013, Olympic speed skater Anastasia Bucsis stated publicly to the Globe and Mail that she was “proud to be gay.” The following year, goalkeeper Erin McLeod came out during a CBC interview. Ten years later, queer athletes like boxer Tammara Thibeault, who qualified for the Paris 2024 Olympics, consider themselves proud members of the LGBTQ2S+ community.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom