Larry Grant (also known as sʔəyəɬəq (suh-yuh-shl-uck) and Hong Lai Hing), storyteller, Musqueam Elder, educator of endangered First Nation language hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ (born 1 September 1936 in Agassiz, BC). Grant is of Musqueam and Chinese ancestry, raised on the Musqueam territory at the mouth of the Fraser River. The unceded territory of the Musqueam peoples encompasses what is known today as Vancouver, extending up to Harvey Creek in the north and Fraser River to the east. After retiring as a longshoreman, Grant dedicated his life to promoting knowledge of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language and its cultural value. He is also an adjunct professor and an Elder-In-Residence at the University of British Columbia. Grant is recognized as a community leader who fosters dialogue and understanding of Musqueam history and language in British Columbia.

Childhood on Musqueam Reserve

Elder Larry Grant is the second of four children between Musqueam matriarch Agnes Grant and Chinese farmer Hong Tim Hing. In the early 20th century, Chinese migrants farmed on the fertile lands of the Musqueam Indian Reserve (see also Reserves in British Columbia). Hong was from a farming village called Sei Moon in the province of Guangdong, China. After arriving in British Columbia, Hong worked on his father’s farm. This farm was situated on land that belonged to Agnes Grant’s father, Seymour Grant.

Hong and Agnes eventually started a family. Growing up Grant hardly saw his father, except for occasional dinners at the bunkhouses where his father lived with other farmers. The Indian Act stipulated that non-Indigenous peoples were not permitted to cohabit on the reserve. This meant that the Grant children lived with their mother on the Musqueam reserve. They were raised with the help of their grandparents and the wider community.

The forced separation of Hong Tim Hing from the Grant family meant that Grant grew up knowing very little about the Chinese side of his ancestry. He identified with his Musqueam ancestry but was recognized by the Canadian government as a Chinese citizen. A sense of not belonging followed him from childhood to youth. The one place where he felt fully accepted was on the Musqueam reserve. His grandfather, Grant said, accepted the children as fully Musqueam.

As a result, he had the benefit of being steeped in the rich linguistic world of the Musqueam community. He recalls watching his mother and aunts at the kitchen table speaking for hours in hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓. They were telling stories that were passed down for generations (see Indigenous Oral Histories and Primary Sources). According to her children, Grant’s mother was the last fluent hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ speaker in the community. She always reminded Grant that their language and history are the anchors of their identity and a bridge to their family and community.

Impact of Legislation on First Nations and Chinese Communities

While Elder Larry Grant lacked a strong connection to the Chinese side of his family, his citizenship status as Chinese created an exceptionally rare set of circumstances; he and his siblings were excluded from attending residential school, which operated in Canada from 1831 to 1996.

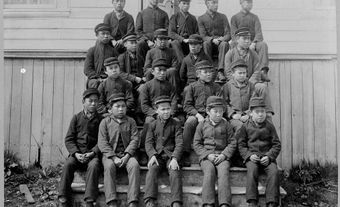

Grant and his siblings, some of the few school-aged children on reserve at the time, participated in underground potlatchs held in the wintertime in the bighouses. They played Slahal games with a set of deer bones and watched winter spirit dancing ceremonies. As youth, they learned to cut and pack wood. They also learned to make fire, in keeping with tradition.

To Grant, the devastating impacts of residential schools were evident after the children returned home. His cousins lacked feelings of self-worth and confidence and were not taught life skills like building a home, building a boat, carving a canoe, hunting and fishing. Grant saw firsthand how the legacy affected the lives of his extended family into their adulthood.

Grant often highlighted the inter-generational legacy of residential schools and the “acts of denial” embedded in legislation, like the Indian Act that denied Indigenous peoples the right to practice their culture and language (see Intergenerational Trauma and Residential Schools). He shed light on the parallels of disenfranchisement experienced by Indigenous and Chinese communities in Canada. Indigenous Peoples were denied integration with the community. Chinese people were denied citizenship and access to land ownership. Both were denied the right to pursue professional careers as doctors, lawyers, engineers and more. Indigenous peoples were denied post-secondary education (see also Anti-Asian Racism in Canada; Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians). The two communities supported each other under these constraints.

Musqueam Elder and Educator

As soon as Elder Larry Grant’s career as a mechanic and longshoreman ended in retirement, his role as an educator and Elder began.

In addition to being a Musqueam Elder, Grant is also an Elder-In-Residence at the University of British Columbia (UBC) First Nations House of Learning. Also, he is an adjunct professor with the UBC Musqueam Language and Culture Program, where he teaches a first-year hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language course. He also served as a language and culture consultant for the Musqueam community.

It took him a while to figure out his role as an Elder-In-Residence, a position he’s held since 2001. “I’m the brother, I’m the dad, I’m the grandpa, I’m the old guy. I have to be a diplomatic person so I’m a diplomat. I have to understand Musqueam culture and history, otherwise, I can’t expound on anything to these Indigenous students.”

The first time Grant spoke hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ publicly was in 2000. The then 64-year-old delivered a welcome in front of a crowd at a UBC event attended by Auntie Irene, a friend of Agnes Grant. “Thinking of all the richness that is embedded in language, in anyone’s language, that was denied to our people, and no one else’s language was prohibited by legislation,” Grant said.

Since he took that first step as a community leader, Grant has yet to slow down. He often gives talks on campus and speaks at cultural events and Indigenous gatherings. As the interim manager of the Nation’s language department, he has been at the forefront of the movement towards reconciliation through renaming various places in Metro Vancouver.

In 2018, UBC unveiled Musqueam street signs on campus as part of a plan that was agreed upon in 2006 (see Indigenous Names of Streets in Canada). In 2022, Grant was involved in the official renaming of Trutch Street in Vancouver. Originally, the street was named after Joseph Trutch, BC’s first lieutenant-governor (see Lieutenant-Governors of BC). He held deeply racist views towards Indigenous peoples and worked to reduce the size of reserves. The name change took years. Now the street is named Musqueamview Street, or šxʷməθkʷəy̓əmasəm.

Grant was also involved in renaming Sir Matthew Begbie Elementary School in Vancouver to ‘wək̓ʷan̓əs tə syaqʷəm’. In hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, this name means “the sun rising over the horizon.” Sir Matthew Begbie was BC’s first chief justice. He was involved in the controversial decision to hang six Tsilhqot'in Chiefs.

Among Grant’s list of accomplishments, his proudest is promoting Musqueam culture to the greater population. “Musqueam is still here and this is our land,” Grant said.

“Accept who you are,” he added. “Be comfortable with who you are and come to reconciliation with yourself so that anchor that our mother talked about becomes a part of you. That is the most significant thing I’ve been promoting as much as I can.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom