The holiday which takes place on the first Monday immediately preceding 25 May has had several names: Victoria Day, the Queen’s Birthday, Empire Day, Commonwealth Day, fête de Dollard, fête de Dollard et de Chénier and Journée nationale des patriotes. This day is at the heart of a conflict between representations and memories. For most people, it represents the arrival of sunny days. (See also National Holidays.)

Flag of the Patriote movement, Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) 1832-1838

Image: Wikimedia Commons

The Queen’s Birthday and the fête de Dollard

During the 18th century, a monarch’s birthday was a military event which marked the start of the local militia’s yearly training. During the 1790s, Prince Edward, sent to British North America, participated in the troupes’ evaluations.

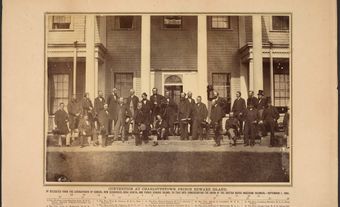

After the unrest provoked by the Rebellions of 1837-1838 and the suspension of parliamentary assemblies in Upper and Lower Canada in February 1838, the new Province of Canada, created under the Union Act of 1840, searched for a way to unite English and French Canadians and express their loyalty to the monarchy in order to distinguish themselves from the Americans (see also Province of Canada (Plain-Language Summary)). In 1845, the legislative assembly proposed to celebrate the birthday of Queen Victoria, who was born on 24 May 1819.

At first, this official holiday was celebrated on the same day as the queen’s birthday. During the second half of the 19th century, the festivities intensified as they coincided with the arrival of sunny days in southern Ontario. Since the celebrations lasted an entire day, it was decided that the holiday would take place each Monday preceding 25 May, thus extending the weekend. When Queen Victoria died in 1901, this Monday was made a national holiday to underline her contribution in forming the Confederation (see also Confederation (Plain-Language Summary)).

In Quebec, during the 1900s and the 1910s, people mostly referred to this holiday as the “long weekend of May”. This highlighted the ambivalence they felt toward the celebration of the British monarchy and imperialism, whose excesses were being tolerated less and less (suspension of French language education, military conscription).

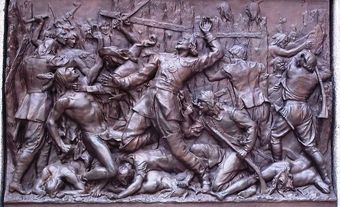

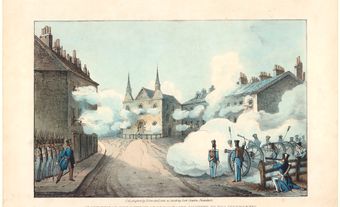

Later, the image of Dollard des Ormeaux was used to encourage French Canadians to enlist for the Great War. Born in France on 23 July 1635, des Ormeaux arrived in New France in 1658. On 21 May 1660, accompanied by 16 volunteers, he led an epic battle against the Iroquois in Long-Sault, resisting an attempted attack on Ville-Marie. He and his convoy died, but their actions allowed the town residents to harvest their crops and escape famine (see also Iroquois Wars). Some nationalists, namely Lionel Groulx, wished for this holiday to commemorate the exploits seen in this battle. The names Dollard and des Ormeaux thus appeared in the toponomy and, as of the 1920s, the day was commonly known as the fête de Dollard.

However, in the 1960s, when historians tried to document the event, they discovered a lack of conclusive evidence necessary to retrace certain elements of history, which by then had become mythical. According to those researchers, des Ormeaux may have left on his own initiative to join the convoy of Indigenous allies to the French and retrieve the furs which had not been delivered for months because of the wars with the Iroquois. He may also have decided to keep the spoils to himself and confronted Iroquois individuals who had the same idea. Dollard des Ormeaux may thus have been, to borrow the words of journalist Raymond Desmarteau, “an unlucky pirate who was also clumsy with powder kegs but praised by religious authorities who were eager to use heroes and martyrs to stir patriotic and religious feelings.” This did not matter much, because the celebration of a victory against Indigenous peoples had started leaving a bitter taste in some mouths, and the entire notion of heroism was starting to become problematic. On another note, des Ormeaux is still present in Franco-Ontarian history, since the battle took place in Long-Sault, in Ontario.

Replacing Dollard by the Patriotes

In November 1937, on the occasion of the centennial of the Rebellions, celebrations took place at Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu. The Patriotes’ battles were again honoured in 1962 during the 125th anniversary and, from that day onwards, they are commemorated each year in November. Gradually, the Rebellions were recalled to memories. Some hoped that the Quebecois would find inspiration in this republican mobilization, while others simply wished to highlight the combat fought by the Patriotes in the name of political freedom and democracy. In May 1968, the television series Le Sel de la semaine selected doctor Jean-Olivier Chénier (1806-1837), who died in the Battle of St-Eustache, as the greatest French Canadian hero. At the end of the show, it was proposed that the fête de Dollard be renamed the fête de Chénier. Calendars sold in Quebec during the 1970s and 1980s referred to the Fête de Dollard et de Chénier.

Nevertheless, this first association between the Patriotes and the Queen’s Birthday followed a sinuous course before being recognized. René Lévesque’s government faced pressures, and, on 6 October 1982, it declared that the Journée des patriotes would be celebrated on the Sunday closest to the 23 November. This was insufficient in the eyes of those who wanted a public holiday to commemorate the Patriotes, whether in November or in replacement of another holiday. In 1987, the Club souverain de l’Estrie launched a campaign about this issue; in 1997, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Montreal started pushing in the same direction and, in 2001, Pierre Falardeau’s movie 15 février 1839 popularized the Rebellions in the collective imaginary.

La Journée nationale des patriotes

In May 2000 during its national convention, the Parti québécois passed a resolution requesting the government to designate an official holiday commemorating the Patriotes to replace an existing holiday. On 20 November 2002, the Quebecois government designated, by Order 1322, the day of the fête de Dollard as the Journée nationale des Patriotes.

Quebec premier Bernard Landry declared that “This public holiday will commemorate the battle fought by the Patriotes from 1837 to 1838 for the recognition of our people on a national level, for its political freedom and for a democratic system of government.” To support the choice of the day, it was reminded that while the rebellion broke out in autumn, it was in May 1837 in Lower Canada that public assemblies started taking place in protest against London’s refusal to honour the Patriotes’ requests.

The first Journée nationale des patriotes was celebrated on 19 May 2003. On that day, the Mouvement national des Québécoises et Québécois (MNQ) aimed to “remember an important moment in our collective course, set to become a landmark in Quebec’s historical conscience”. Since 2010, the Fondation Lionel-Groulx has been collaborating with the MNQ to promote the Journée nationale des patriotes. On 20 May 2013, Saint-Eustache launched its self-guided tour “Sur les traces des patriotes” (“following in the Patriotes’ footsteps”). In Montreal, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste hosts a heritage tour on foot which goes through Old Montreal among other places and includes theatrical capsules. Each year from 2005 to 2018, the Rassemblement pour un pays souverain awarded the Louis-Joseph-Papineau prize to figures who had demonstrated their engagement to Quebec.

The holiday nowadays

Only Canada still celebrates Victoria Day. In 2013, English Canadian actors, writers and politicians, including Margaret Atwood, Gordon Pinsent and Elizabeth May, signed a petition to request that premier Stephen Harper rename the holiday “Victoria and First Peoples Day” to commemorate the relationship between the Crown and the First Nations and designate a public holiday in honour of Indigenous peoples (National Indigenous Peoples Day, celebrated on 21 June, does not have this status). However, the petition was signed by only a few thousand people and did not convince the legislators (except for the Green Party) to pick up the campaign.

The coexistence of Victoria Day and the Journée nationale des patriotes is an example of the national duality in Canada and of the country’s conflicting memories. Business signs commonly say “Open for Victoria Day / Ouvert pour la fête des patriotes”. Despite this disagreement, the holiday is still an opportunity to enjoy a meal outdoors and to plant flower seeds without the fear of frost.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom