Africville was a Black Canadian village located just north of Halifax, Nova Scotia and founded around the mid-19th century. The City of Halifax demolished the once-prosperous seaside community in the 1960s in what many said was an act of racism. The mayor of the Halifax Regional Municipality apologized for the action in 2010. For many people, Africville represents the oppression faced by Black Canadians, and the efforts to right historic wrongs.

Origins

Halifax was founded in 1749, when enslaved African people dug out roads and built much of the city. Some evidence indicates that this early Black community lived a few kilometres north of the city on the southern shore of the Bedford Basin — an area that became Africville. Other evidence suggests that some of the Jamaican Maroons (Africans who escaped enslavement), resettled to Nova Scotia by the British government, moved to the basin in 1796.

The first record of settlement in the Africville area is from 1761. The land was granted to several white families, including the families of men who imported and sold enslaved African men and women. In 1836, Campbell Road connected central Halifax to the Africville area. It is likely that several Black families lived in the area, earning it the nickname “African Village.” They were a mix of formerly enslaved people, Maroons, and Black refugees from the War of 1812. Many of these refugees were themselves once enslaved in the Chesapeake area of the United States.

In 1848, William Arnold and William Brown, both Black settlers, bought land in Africville. Other families followed and in 1849 Seaview African United Baptist Church was opened to serve the village’s 80 residents. (See Baptists.) The church was called “the beating heart of Africville” and was the centre of the village to both church-goers and non church-goers. It held the main civic events, including weddings, funerals, and baptisms. The church’s baptisms and Easter Sunrise Services were well-known. Black Nova Scotians, as well as white Nova Scotians, would line the banks of the Bedford Basin to watch the singing procession leave the church to baptize adults in the basin’s waters. After much petitioning by Africvillians, a school opened in 1883. Previously, a local resident had taught many of the children in Africville before the City school opened.

Taxes, but No Services

Africville residents ran fishing businesses from the Bedford Basin, selling their catch locally and in Halifax. Other residents ran farms, and several opened small stores toward the end of the 19th century. It was a haven from the anti-Black racism they faced in Halifax (see Prejudice and Discrimination). In the city, Black women were generally only able to find work as domestic servants and where men were limited to a few jobs such as sleeping car porters on trains. Children swam in Tibby’s Pond and played baseball in Kildare’s Field. In the winter, everyone played hockey when the pond froze.

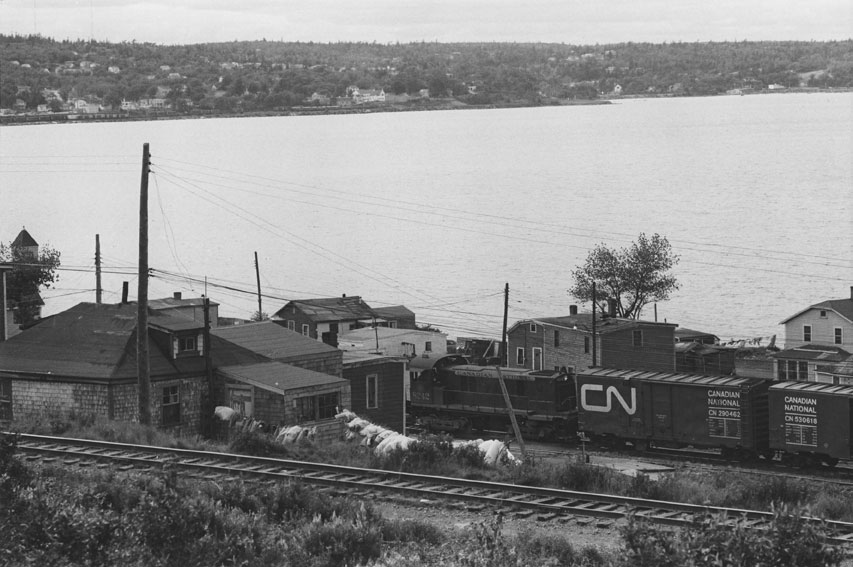

The City of Halifax collected taxes in Africville, but did not provide services such as paved roads, running water, or sewers. In 1854, a railway extension was cut through the village. Several homes were expropriated and destroyed. Some homeowners protested that they had not been paid for their land and that the speeding trains posed a danger and polluted the village. More land was expropriated for the railway in 1912 and in the 1940s. In the first half of the 20th century, municipal services such as public transportation, garbage collection, recreational facilities, and adequate police protection were non-existent in Africville.

The City of Halifax continued to place undesirable services in Africville in the second half of the 19th century. These included a fertilizer plant, slaughterhouses, Rockhead Prison (1854), the “night-soil disposal pits” (human waste), and the Infectious Diseases Hospital (1870s). In 1915, Halifax City Council declared that Africville “will always be an industrial district.” Many Africville residents believed anti-Black racism was behind these decisions.

The Halifax Explosion

In 1917, the Halifax Explosion shelved plans to turn Africville into an industrial zone. The disaster levelled much of Halifax’s North End and damaged Africville. A global relief effort brought in millions of dollars in donations to rebuild the city, but none of the money went to rebuilding Africville. Halifax did not survey Africville for damage, but oral history records that several homes were badly damaged and lost their roofs. About four Africvillians died, although it is thought that they were in the North End when the explosion hit.

Throughout the 1930s, residents petitioned the city to provide running water, sewage disposal, paved roads, garbage removal, electricity, street lights, police services, and a cemetery. Their requests were largely denied.

In the 1950s, Halifax built an open-pit garbage dump in Africville. The city considered several locations, but council found it was unacceptable to residents in places such as Fairview. One alderman said the dump was “a health menace” and should not be placed in Fairview. Council voted to put the dump 350 metres from the western edge of Africville. There is no reference in the council minutes to any concern for the health of Africville residents, or of any consultation or protests from Africvillians.

By the 1960s, many white Halifax residents referred to Africville as a slum built around the dump by scavengers. Seeing Africville as a “slum” formed an important part of the public acceptance of Africville’s destruction.

Africville’s school was closed in 1953 as Nova Scotia de-segregated its education system. (See also History of Education; Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.) In practice, this meant closing many Black schools and bussing pupils to the nearest white schools. As such, Africville students went to schools in Halifax. Many faced discrimination and were channeled into “auxiliary” classes that had few resources.

Culture

Africville was a culturally significant place. The Africville Brown Bombers were a popular team in the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes — a business largely run out of Africville — and drew big crowds from the CHL founding in 1895 until it closed in 1930.

In the 1960s, boxer Joe Louis (1914–81) visited Africville. Louis was in Halifax to referee a wrestling match and asked where all the Black people lived. He was told Africville, and so he went to see it for himself. In fact, Africville produced the first Black boxing world champion: George Dixon (1870–1908).

Africville has a strong connection to music. The Seaview African United Baptist Church was well-known for its preachers and music. The singer Portia White (1911–68) worked as a schoolteacher in Africville. American musician Duke Ellington (1899–1974) visited Africville in the 1960s. Ellington’s father-in-law was from Africville and he stayed to visit family.

Despite difficult living conditions and Africville’s growing reputation as a “slum” in the 20th century, residents generally maintained a deep pride in their community. It was seen as a rural idyll apart from Halifax. Many cited the people and the seaside location, with one well-travelled resident calling it “one of the most beautiful spots I’ve been in.”

“Urban Renewal”

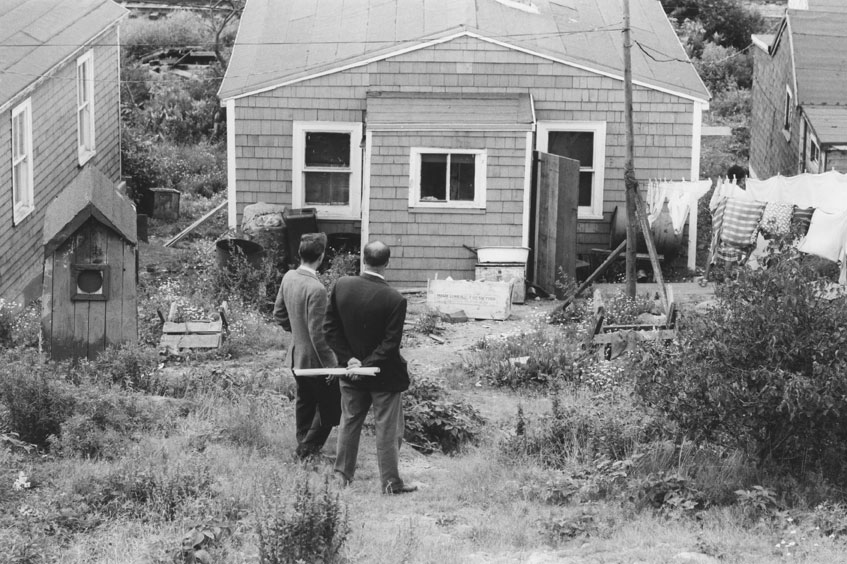

Plans to turn Africville into industrial land were revived and approved by Halifax City Council in 1947, when the area was rezoned for that purpose. Reports prepared for council in 1956 and 1957 recommend re-housing residents to make way for industrial projects. In 1962, the city approved plans for an expressway to downtown Halifax that would run over Africville, but it was never built.

At a public meeting in Africville in 1962, 100 Africvillians voted strongly against relocation, preferring to improve the existing community. In an interview at that time with the CBC, homeowner Joe Skinner explained that Africville was a place where Black people were free and that he did not want to move into Halifax to end segregation. “I think we should have a chance to redevelop our own property as well as anybody else,” he said.

Joe Skinner:

“When you are in this country and you own a piece of property, you’re not a second-class citizen. That’s why my people own this land, they worked for it, they toiled for it. It is land that they own, and they try to hang on to it. But when your land is being taken away from you, and you ain't offered nothing, then you become a peasant — in any man’s country.”

Halifax council voted to remove the “blighted housing and dilapidated structures in the Africville area.” The city promised a process of “urban renewal” where residents would be relocated to superior housing in Halifax. (See also Urban Reform). The first land was expropriated in 1964. Homes were bulldozed lot by lot over the next five years. Some residents were moved to derelict housing or rented public housing. When a city-organized moving company cancelled, Halifax brought in dump trucks to move residents and their possessions. The stigma of being from Africville was compounded when families arrived at their new homes on the back of dump trucks.

Locals likened Africville to a warzone, with houses disappearing daily. Several homeowners found that their homes had been bulldozed without their knowledge or permission. Others had only a few hours’ notice before the bulldozers came. One man returned from a hospital stay to find that his house had been destroyed. Many left with what they could carry. The Seaview United Baptist Church was destroyed in the middle of the night in the spring of 1967. Many residents saw this as the death knell for the community. Expropriation sped up as residents took what deals they could and left.

In 1969, the final property was expropriated and demolished, and the last of Africville’s 400 residents left. One resident, 24-year-old Eddie Carvery, returned to the site of Africville in 1970 and pitched a tent in protest. Demanding a public inquiry and individual compensation for community residents, he actively occupied the site on and off for over five decades. In November of 2019, Carvery’s protest camp at Africville was dismantled. It was one of the longest civil rights protests in Canada’s history.

Aftermath

After the relocation, displaced residents found that the “home for a home” deals did not materialize. Many realized that the sum paid for their land and property was only enough for a downpayment on a new home, or for a short period of rental in public housing. Jobs were still hard to find as many companies refused to hire Black people. Lacking a church or any communal spaces, the displaced residents drifted apart. Some moved to Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. Those who stayed in Halifax felt forced to turn toward welfare to cover the rising costs of life in the city.

In 1969, residents formed the Africville Action Committee in order to seek redress and to keep the community alive. The Africville Genealogy Society was formed in 1983 for the same purpose and former residents began holding picnics, church services and weekend gatherings on the site of Africville.

The land of Africville was turned into private housing, ramps for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge, and the Fairview Container Terminal. The central area was turned into a dog park called Seaview Park.

The site was declared a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996. The citation called it “a site of pilgrimage for people honouring the struggle against racism.” On 24 February 2010, Halifax Regional Municipality Mayor Peter Kelly apologized for the destruction of Africville and said that the city would build a replica church. The church museum opened in 2012, and the area was renamed Africville Park. (See also City Parks). On 30 January 2014, Canada Post Corporation issued a commemorative stamp depicting a photograph of seven young girls — all community members — against an illustrated background of the village.

Former Africvillians and their descendants continue to hold summer reunions in the park, with many camping on the site of their former homes. The church museum began holding Christmas services in 2012.

In February 2020, on Nova Scotia Heritage Day, the provincial government announced that a bell which once hung in the Seaview United Baptist Church would be returned and placed on the land outside the Africville Museum. The bell, which survived the church demolition in 1967, had been held in safekeeping at a church in Beechville for over 50 years.

Africville today is a potent symbol in the fight against racism and segregation in Nova Scotia and beyond.

Remember Africville, Shelagh Mackenzie, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom