Black Canadian communities continued to expand through migration despite racist measures implemented against them. Many communities were tied to the rail industry, as many Black Canadians worked as porters. Others worked in important sectors like mining and farming. Communities bonded together through many associations that advocated for their rights, such as unions and the Universal Negro Improvement Association of Canada (UNIA). Despite the hostility, Black Canadians contributed to Canada’s victory in both World Wars. Famous Black musicians like Oscar Peterson also brought international fame and prestige to Canada’s music scene. The Black community helped redefine Canada’s post-war image, as the country became the proving ground for racial integration in professional sports. This heralded the landscape of sports and entertainment that we see today.

See also Black History in Canada until 1900 and Black History in Canada: 1960 to Present.

Black Communities in the Early 20th Century

After the 19th-century influx of Fugitives (see Underground Railroad), the next great migration was African American railroad workers. These men were mainly recruited out of Winnipeg, Toronto, and Montreal for jobs on Canada’s burgeoning railroads. For the first half of the 20th century, Black community development was deeply connected with the fortunes of Black railroad employees and their families.

For this reason, Black communities emerged around train stations, such as Windsor Station in Montreal. This was repeated in Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, where Black districts with businesses and churches took root to meet the needs of porters and their families. In these urban pockets, Black social and cultural institutions often thrived.

In the rural Maritimes, seasonal migration brought many West Indians to work in coal mines, steel mills and shipyards. They joined mainstream churches and created institutions that reflected Black independence, self-reliance, mutual support and racial pride.

The migration of African Americans to the Prairies was not as easy, as approximately 1,000 arrived in Alberta and Saskatchewan between 1908 and 1911. They joined millions of European homesteaders. African Americans on the Prairies established towns, including Eldon, Amber Valley, Campsie, Keystone (now Breton) and Junkins (now Wildwood).

Though their community life had deep generational roots connected to the land, multigenerational Black families (descendants of Refugees, Loyalists and Maroons) found it difficult to sustain unproductive farms and keep their families intact. They worked hard to build social cohesion within fraternal associations like the Masons, the Elks and the Lodges, as well as denominational churches. Still, these communities began to dwindle in numbers as children increasingly moved west into cities.

First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War, a large number of Black Canadians tried to volunteer for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. They became painfully aware of the concept of “a white man’s war” when they were refused. Black Canadians protested their exclusion. In response, General Willoughby Gwatkin proposed the formation of one or more Black labour battalions as a compromise. The No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized on 5 July 1916 and sailed overseas in March 1917. Comprised of Canadians, Americans and West Indians, this battalion was the first and only all-Black battalion in Canadian military history.

On the home front, Black women fundraised for the war effort. However, other measures they wanted to support were muted, as Black women were not permitted to join the Canadian Red Cross and other mainstream women’s groups. Instead, they mobilized their efforts within local auxiliaries. The money raised paid for the medical care, burials and births of community members.

In 1916, before war’s end, the Glace Bay Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), one of the first Canadian divisions of the UNIA, opened in Nova Scotia. This organization was spearheaded by West Indian migrants who were already familiar with the teachings of Marcus Garvey, founder of the UNIA. After the war, West Indians living elsewhere in the country —most notably, in Montreal, Toronto and Edmonton — established their own UNIA divisions. For a time in Canada, the UNIA was the most important Black socio-economic and educational force. Moreover, the UNIA, with more than 1,000 chapters in 40 countries and millions of members, became one of the most important political and social organizations in history.

Interwar Period

Close to 90 per cent of all Black men in Canada were associated with railway employment (see Sleeping Car Porters; Black Canadians). These jobs were severely underpaid and had abysmal working conditions. Since the turn of the century, Black men had agitated in secret for a labour union. As negrophobia ( see Racism) got its second wind after the war, it became increasingly important to gain recognition. In January 1919, the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP), the first Black railway union in North America, was finally recognized.

As 1919 dawned, a national Prohibition campaign closed off liquor to venues, including those featuring jazz, in the United States (see also Temperance Movement in Canada). Montreal’s own Prohibition initiative was defeated in a referendum, and Montreal quickly became known as a “wet” city. Consequently, jazz musicians from the northeastern United States — particularly Harlem — streamed into Montreal throughout the 1920s. Many businesses in the porter community of Saint-Antoine catered to jazz culture. Montreal became one of the top jazz centres on the continent until the Second World War (see also Oscar Peterson; Joe Sealy; Oliver Jones; Rockhead’s Paradise).

DID YOU KNOW?

A “wet” city refers to a city that allows for the sale and consumption of alcohol. An area that is “dry” does not allow alcohol to be sold and consumed or even possessed. Today, certain Indigenous communities in the Canadian North have alcohol prohibitions in place that are enforced by the RCMP.

Black organizations increased significantly during the 1920s. Alongside the UNIA and local churches, social and financial needs were met through a plethora of associations, including the Masons, the Elks, Pride Lodges, women’s porter groups and credit and real estate collectives. These independent endeavours often emulated the economic goals of the UNIA, which called for Black self-sufficiency.

Great Depression

During the 1929 Great Depression, upwards of 80 per cent of porters were unemployed. Other Black workers were also hit hard. (See also Black Canadians.) The situation strained community resources, but organizations continued to play a vital role in maintaining stability. As the decade wore on, some African Americans returned to the United States. While rural townships adjusted to the loss of their Black youth, the proportion of Canadian-born Black residents increased in major cities.

In the 1930s, Canadian railroad companies reclassified work categories to limit Blacks to being porters only. Porters renewed their battle for labour equity and found themselves having to fight for union rights. Porters also financed challenges in the courts, the legislatures and their communities against discriminatory practices that hindered their daily lives. After nearly seven decades of unionization efforts, on 18 May 1945, Black porters won a collective agreement that, for the first time, protected Black labourers from arbitrary dismissal. As a result of increased salaries and paid vacations, many porters became financially secure for the first time.

Second World War

As the Second World War began, the military once again restricted Black enlistment. Moreover, until 1942, the National Selective Service, Canada’s national employment agency, also allowed for employers’ racial restrictions in hiring practices. (See Racism.) Local leaders led the charge against the government’s discriminatory policies in the military and its departments. Though Black Canadians maintained public pressure, it was the significant losses of soldiers that eventually pushed the military to relax restrictions. Thereafter, hundreds of Black subjects from the British Commonwealth came to Canada to enlist. Domestically, manufacturing industries employed Black workers for the first time, even though labour segregation persisted on the railroads throughout the war years.

Immigration

At the turn of the century, Canada as a young nation was very aggressive in its recruitment from Europe, South Africa and America. In contrast, Canadian immigration policies severely limited Black immigration. (See also Immigration to Canada.) The exception was male rail workers. Right into the 1950s, railway companies provided Black workers a way to bypass Canada’s immigration restrictions. (See also Black Canadians.)

The fight against racist immigration policies intensified with the Canadian government’s attempt at banning Black immigration to Canada in 1911 (see Order-in-Council P.C. 1911-1324). Several decades later, Black organizers pushed for increased immigration from the West Indies. Reticent to change its “white if possible” immigration preferences, Canada’s immigration department relented only after the war. From 1955 to 1967, Canada permitted the immigration of Black women but only as domestic workers. Nonetheless, they took advantage of their permanent residency status to sponsor relatives to migrate to Canada. Finally, Canada’s Black population underwent a significant population increase.

Human and Civil Rights

During this period, a significant portion of Black activism centred on acquiring human and civil rights. As early as the 1920s, Black organizations challenged local ordinances, provincial laws and national policies that aimed to segregate Black Canadians. (See Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.) The struggles varied. In some communities, this meant fighting exclusion from cultural and social organizations and agitating against chronic underfunding of Black-area schools. Some fought by lobbying to open parks and pools to Black Canadians, as well as desegregate seating in theatres and churches. There were even sit-ins to force hotels, motels, inns and local eateries to serve Black customers.

With the Racial Discrimination Act of 1944, Ontario took the lead in passing human rights legislation. Other provinces slowly followed suit. The most comprehensive anti-discrimination protections were passed in Saskatchewan (1947). (See Saskatchewan Bill of Rights.) The last province to affirm the human and civil rights of Black Canadians was Quebec (1964). The passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960 set the stage for renewed challenges for Black equality in the federal sphere. Unfortunately, the courts’ slow pace in overriding commercial interests meant that racial discrimination cases were difficult to win well into the 1960s.

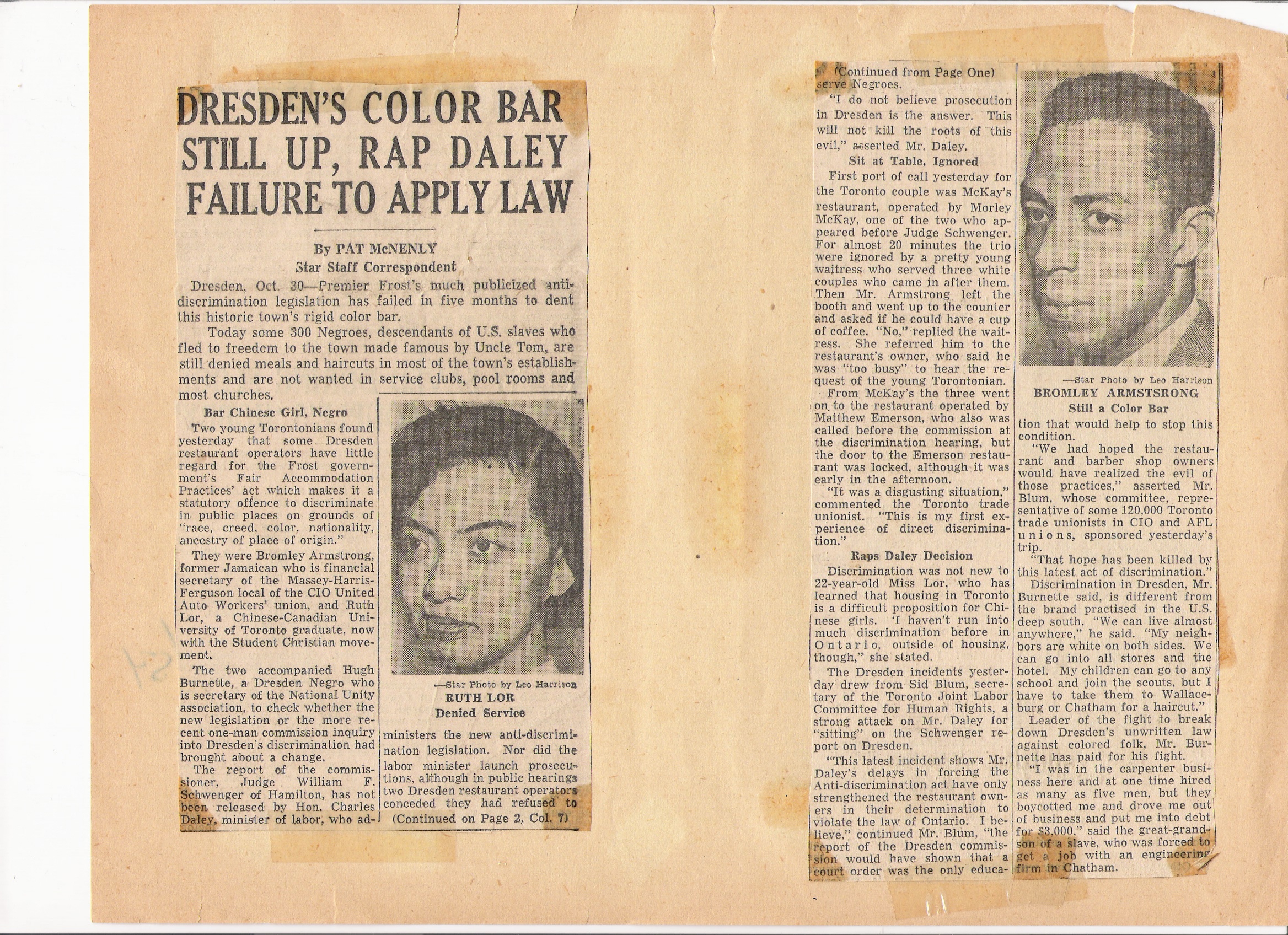

In 1954, Dresden, Ontario, became a point of contention after the province passed the Fair Accommodation Practices Act. Despite the law, Black Canadians found that they were still unable to get service in some Dresden cafés and restaurants. A series of high-profile newspaper articles went national, but despite the negative press, Dresden continued to defy the law. A coalition of social justice groups over the years pressured the government with spot visits, sit-ins and testing. (See Hugh Burnett.) They hoped that their documented actions would prompt authorities to enforce provincial human rights laws in Dresden. Eventually, court cases and fines wore down the most recalcitrant, and Dresden reluctantly began to serve Black customers.

Although some Black men had the right to vote, this was not the case for every Black Canadian in the early 20th century. Black women had to advocate for their right to vote in Canada. Men who did not own property also did not have the right to vote, which excluded many poorer Black Canadians from voting. It was not until 1918 that Black women could vote in federal elections and not until 1920 that property ownership was removed as a prerequisite to vote. However, it took until 1940 for all provinces to allow women, including Black women, to vote. (See Black Voting Rights in Canada; Women’s Suffrage in Canada.)

Integration as Leisure

Prior to 1960, Canada made significant gains in the integration of Black athletes in professional sports. Despite barriers that blocked integration in many spheres of daily life, Canadians were willing to consider integration in sports entertainment. The first and most high profile was Jackie Robinson. Robinson signed on with the Montreal Royals in October 1945. He played on the Dodgers’ farm team for one year and helped Montreal win the Triple-A International League “Little World Series.” That same fall, Herb Trawick was asked to join the Montreal Alouettes in the Canadian Football League, making him the first Black professional football player in Canada. Finally, integration in hockey came about on 18 January 1958, when Willie O’Ree from New Brunswick skated onto the ice with the Boston Bruins.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom