Black people have lived in Canada since the beginnings of transatlantic settlement. Although historically very few arrived directly from their ancestral homeland in Africa, the term "African Canadian" is used to identify all descendants of Africa regardless of their place of birth. “Black Canadian” is also used as a more general term. The earliest arrivals were enslaved people brought from New England or the West Indies. Between 1763 and 1900, most Black migrants to Canada were fleeing enslavement in the US. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.)

See also Black History in Canada: 1900–1960 and Black History in Canada: 1960 to Present.

Enslavement

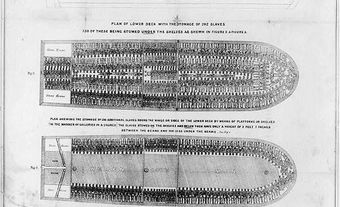

Olivier Le Jeune is the first enslaved person to have been transported directly from Africa to Canada. He was brought to Québec in 1629 in but apparently died a free man. From then until the British Conquest (1759-60), approximately 1,000 Black people brought from New England or the West Indies were enslaved in New France (see Black Enslavement in Canada). Local records indicate that by 1759 there had been a cumulative total of 4,092 enslaved people in New France, including 1,443 of African origin. Most enslaved Africans were domestics rather than fieldhands. (See also Marie-Joseph Angélique.)

Most enslaved people lived in or near urban centres like Montreal, Québec City, Detroit, Halifax and St. John. There was a temporary influx of enslaved people into British North America after the American Revolution when Loyalists immigrated and brought about 2,000 enslaved Black people into British North America. The distribution of these migrants was uneven, with Ontario and Nova Scotia seeing the most significant increase in the number of enslaved people. Up to 3,500 free Black Loyalists who had won their freedom through allegiance to Britain also emigrated to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Among the Loyalists were many abolitionists who challenged societal attitudes and the casual acceptance of enslavement. Within two decades, the practice had virtually disappeared in the Canadas. In 1793, Upper Canada became the only colony to begin passing laws for the gradual abolition of enslavement. There were two unsuccessful attempts to abolish enslavement in the legislature in Lower Canada. However, enslavement’s death knell came after several controversial judicial decisions freed runaway slaves in the province. By 1800, courts in other parts of British North America also limited the expansion of enslavement. Within the next decade, the international embargo on the slave trade on the high seas became increasingly effective at stemming the flow of enslaved people to North American markets. The practice of having enslaved people declined. Enslavers felt forced to sell their enslaved people to American or West Indian buyers. On 28 August 1833, the British Parliament passed a law abolishing enslavement in all British North American colonies; the law came into effect on 1 August 1834.

Black Migrations

After the American Revolution, Black Loyalists settled in almost all the provinces east of Manitoba. In Upper Canada, Black Loyalists joined Black communities settled in several small towns and villages between Windsor and Toronto. In Lower Canada, Loyalists with enslaved Black people settled in the Eastern Townships between the border and the St. Lawrence River. (See Black Enslavement in Canada.)

Following the influx of free Black Loyalists, other Black people entered British North America. In 1796, Jamaican Maroons were exiled to Nova Scotia. The Maroons were descendants of enslaved Black people who had escaped from the Spanish, and later the British rulers of Jamaica. Maroons were feared and respected for their courage. For four years, the Maroons worked on various public projects. However, given the poor provisions for their basic needs, the Maroons successfully petitioned to emigrate. In 1800, hundreds of Maroons left Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone.

Then, between 1813 and 1816, around 2,000 formerly enslaved people who had sought refuge behind British lines during the War of 1812 were sent to Nova Scotia. This group, known as the Black Refugees, settled in various townships in Nova Scotia. Another thousand or so Black Refugees moved into New Brunswick and established settlements there.

The 1820s saw a trickle of fugitive slaves from the United States. Eventually, these fugitives from American slavery crossed into British North America in increasing numbers, using the secret routes of the Underground Railroad. By the time of the American Civil War, it is estimated that around 30,000 fugitives had escaped to Canada.

West of the Rockies, in the late 1850s, about 800 free African Americans were invited to migrate from California to Vancouver Island to assist British authorities. They were motivated to leave by the racial discrimination imposed by law in their home state. (See also Prejudice and Discrimination; Racism.)

With the end of American slavery in 1865, many thousands of African Americans returned to the US. At the same time, Canada’s burgeoning rail industry encouraged African Americans and West Indians to immigrate for jobs. In the latter quarter of the 19th century, this was particularly the case for Pullman porters. Cities like Montreal, Winnipeg and Toronto saw increased populations of Black rail workers and their families.

Settlement Patterns

In the Maritimes, government policy set up segregated communities for Black Loyalists, Maroons and Refugees on the outskirts of larger white towns. Some major cities, Halifax, Shelburne, Digby and Guysborough in Nova Scotia and St. John and Fredericton in New Brunswick, had all-Black settlements in their immediate neighbourhoods. (See Africville.)

In Quebec, many enslaved Loyalists had been taken to the Eastern Townships, but their sojourn there was short-lived. Black fugitives and settlers gravitated to Old Montreal by the port (see Montreal). Over time, Black residents moved into Montreal’s southwest wards to be near their railway jobs.

In Ontario, the Underground Railroad fugitives tended to concentrate in self-sufficient settlements. Places like Elgin Settlement, Dawn and Oro were built for mutual support and protection against white Canadian prejudice and discrimination, as well as the threat from American slave-catchers. Most of Ontario's Black settlements were in and around Windsor, Chatham, London, St. Catharines and Hamilton. Toronto had a predominantly Black neighbourhood. There were also smaller concentrations of Black Canadians near Barrie, Owen Sound, Niagara and Guelph.

Early Black Canadians’ settlement on the prairies was sparse, but a few Black people lived in clusters around Melfort, Saskatchewan, in Glenbow, Alberta or near the big cattle ranches. Farther west, Governor James Douglas had invited Black Californians to settle in British Columbia. They settled on Salt Spring Island and made the city of Victoria their home. By the turn of the century, a Black community was taking hold in the lively district of Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver.

Economic Life

Poverty has been a basic component of Black people’s early experiences in Canada. The Black Loyalists, Maroons and Refugees met with numerous obstacles trying to establish themselves in the Maritimes. The small land grants they received could not permit self-sufficiency through agriculture. Forced to seek occasional labouring jobs in neighbouring white towns, Black Canadians were vulnerable to exploitation and discrimination in employment and wages ( see Prejudice and Discrimination).

Partly as a result of poor living conditions, substantial numbers of Black people left Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. In 1792, almost 1,200 Black Loyalists sailed from Halifax to found the new settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone. Then, in 1800, when Maroons also left for Sierra Leone, they helped suppress a rebellion of the earlier Black Loyalist settlers against their British governors. The exodus from the Maritimes finally ended in 1820 when some 95 Black Refugees left Halifax for Trinidad.

Though encouraged to migrate, most Black Refugees remained. Still, it was difficult as their grinding poverty worsened due to poor agricultural prospects and severe winters. The hostile competition of an abundant white labour force ensured Black workers remained in low-wage jobs.

Black fugitives in Ontario often became labourers on the lands of others, although some farmed their own land successfully. For a while, Black businesses enjoyed some measure of success in Black settlements. After the Civil War, in major cities like Montreal and Toronto, the economic life of Black men increasingly centred around their employment on the railroads. Meanwhile, local entrepreneurs thrived on catering to porters’ needs: barbers, rooming houses, halls, cafes, etc.

Those who migrated to Victoria, British Columbia, in the 1850s were successful merchants in California. Unsurprisingly, upon arrival they established small businesses. Less skilled Black labourers farmed or worked in shops. Like most Black Canadians, they were employed in low-paid jobs or as unskilled labour.

Community and Cultural Life

In their concentrated settlements, the early Black Canadians had the opportunity to retain cultural characteristics and create a distinct community. Styles of worship, music and speech, family structures and group traditions developed in response to the conditions of life in Canada. The chief institutional support was the separate church, usually Baptist or Methodist (see Methodism), created when white congregations refused to admit Black believers as equal.

The churches' spiritual influence pervaded daily life. The clergy often assumed a major social and political role. The many fraternal organizations, mutual assistance bands, temperance societies and antislavery groups formed by 19th-century Black people were almost always associated with one of the churches and often at the behest of the women.

In Canada, Black women have always played an important economic role in family life and experienced considerable independence as a result. Raised in a communal fashion, frequently by their grandparents or older neighbours, Black children developed family-like relationships throughout the local community. A strong sense of group identity and mutual reliance, combined with the unique identity provided by the churches, produced an intimate community life and a refuge against white discrimination.

Military

A tradition of intense loyalty to Britain and Canada developed among Black Canadians early on. The Black Loyalists fought to maintain British rule in America, and their awareness that an American invasion could mean their re-enslavement prompted them to participate in Canada's military defence. Black militiamen fought against American troops in the War of 1812. Black soldiers were prominent in subduing the Rebellions of 1837–1838 and later helped to repel the Fenian incursions.

For a period in the 1860s, the largely self-financed Black Pioneer Rifle Corps was the only armed force protecting Vancouver Island. The Corps, however, was later denied the opportunity to participate in the Vancouver Island Volunteer Rifle Corps.

Education

In New France, the desire to ensure that household enslaved people conformed to Catholic rites and beliefs meant that they could be educated. Throughout the 19th century, Black Canadians’ education suffered from unequal access to resources. Up to 1900, Black people in Quebec — those who could afford it — were schooled in Protestant institutions. But in the Maritimes, Black schools were almost exclusively run by British charitable organizations. British and American societies also established schools for Black people in Ontario.

Both Nova Scotia and Ontario created legally segregated public schools. With inadequate funding, combined with residential isolation and economic deprivation, poor schooling helped to perpetuate limited opportunities and restrict mobility.

Politics

With slavery at its foundation, Canadian law did not favour an equal legal status for Black people. From 1628 to 1763, laws in New France upheld the enslavement of Black people. Despite the gradual abolition of the practice of enslavement in British North America, there were nonetheless attempts at limiting Black Canadians’ political rights. In the 19th century, Black women were partially disenfranchised and lost the right to vote in some elections. Many of these women fought for their rights in the suffrage movement.

Several Black leaders made significant contributions to Canadian politics. Many were municipal councillors and school trustees. These included, for example, Mifflin Gibbs, who sat on the Victoria City Council in the 1860s and was a delegate to the Yale Convention deliberating British Columbia's entry into Confederation. Another notable Black politician was William Hubbard, who served as councillor, controller and acting mayor of Toronto from 1894 to 1907.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom