Canada has been a part of the story of powered flight since its earliest days. Numerous Canadians have applied their talents and vision to advance aviation and all of its related sciences. The following are just a few examples of Canadian innovation in this field.

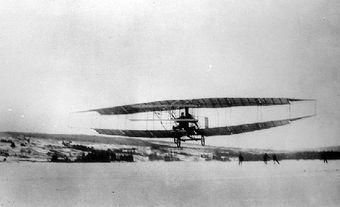

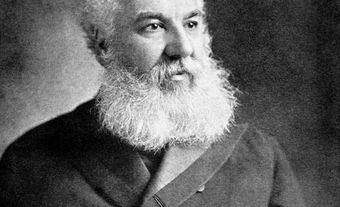

Silver Dart

The Silver Dart was the first controlled, powered, heavier-than-air machine to fly in Canada and in the British Empire. It was designed and built in 1908 at Hammondsport, New York, by the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), which was founded by Alexander Graham Bell and funded by his wife, Mabel Bell (née Hubbard). Designed by J.A.D. McCurdy, the aircraft was 12 m long and had a wingspan of 15 m. It weighed 277 kg empty. Important innovations were the adjustable flaps on the wings and the water-cooled engine developed by Glenn H. Curtiss. The machine’s wing surface areas were covered by a silver-coloured, rubberized fabric, which inspired its name. After several successful flights at Hammondsport, the machine was dismantled and transported to Baddeck on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, where Bell had a summer residence. On 23 February 1909, the Silver Dart was towed onto the ice of Baddeck Bay. McCurdy piloted the aircraft, with a crowd of just over 100 spectators in attendance. On its second attempt, the machine rose into the air after travelling about 30 m and flew for a distance of 800 m at a 9 m altitude at about 65 km/h. The Silver Dart continued to make more than 200 successful flights until it was irreparably damaged during military trials at Petawawa, Ontario, in August 1909.

JN-4 Canuck

The fighter planes of the First World War were notoriously difficult to operate. Casualties among Allied airmen grew as poorly trained and inexperienced pilots became easy prey for German aces. The Royal Flying Corps (later the Royal Air Force) began establishing flying schools in Canada in 1916 so that novice pilots could receive training that would give them a better chance of survival in the deadly skies above the Western Front. (See also Military Aviation.) A new company, Canadian Aeroplanes Limited, was created to manufacture aircraft for training purposes. This company made improvements on the Royal Flying Corps’ preferred trainer, the Curtiss JN-3, and developed the Curtiss JN-4, better known as the JN-4 Canuck. The JN-4 Canuck was better suited for military training and was the first aircraft to be mass-produced in Canada. The Canuck became the most important trainer for Canadian and British pilots and was also used by the United States Army Signal Corps. After the war, many of them were adapted for civilian use.

Avro Arrow

The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow, popularly known as the Arrow, was a product of the Cold War, in which the adversaries were the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Soviet Union and its allies (the Warsaw Pact) (see Canada and the Cold War). The Arrow was a supersonic interceptor jet designed and built in Canada for the purpose of defending Canada’s Arctic airspace from Soviet aircraft. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) had specification requirements for the Arrow that surpassed those documented in any other nation in the Western world. They called for an aircraft that could operate from an 1830 m runway, accelerate to Mach 1.5 and have a range of 556 km while carrying a crew of two and possessing an advanced computerized flight control and weapons system. The Arrow’s first test flights were conducted in early 1958. It set new speed records to become the world’s fastest fighter jet at the time and proved to be one of the most advanced aircraft of its day, establishing Canada as an international leader in scientific research and development. However, in February 1959, the Conservative government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker cancelled all work on the Arrow due to costs and other military developments.

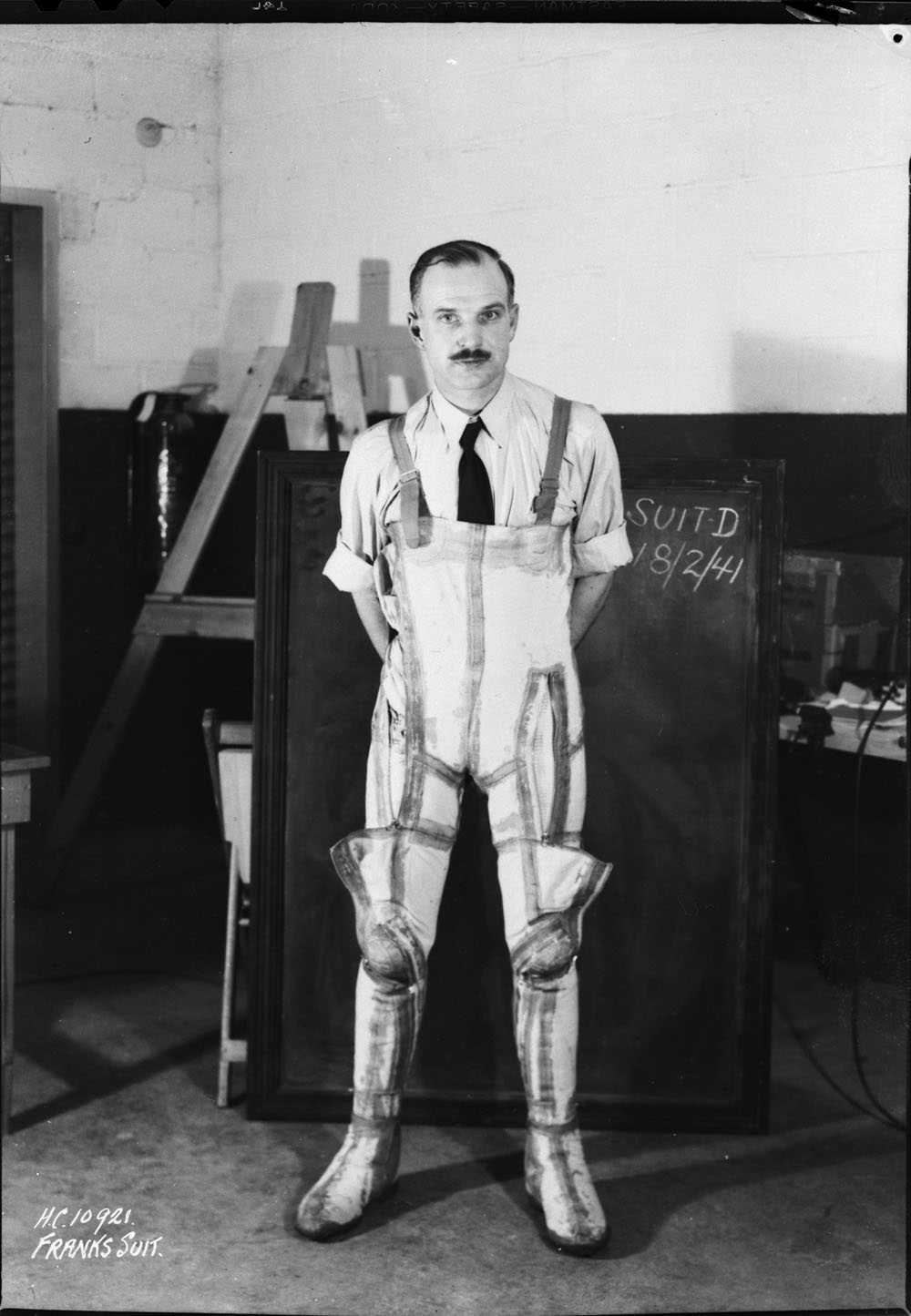

Franks Flying Suit

The evolving nature of warfare during the Second World War required military aircraft to fly at speeds and altitudes that subjected pilots and aircrews to extremes of physiological and psychological stress, which no one had previously experienced. Canadian research teams broke new ground and made significant contributions toward aviation medicine — a field of medicine that was still in its infancy. One of the most important Canadian innovations was the anti-gravity suit, or G-suit, also known as the Franks Flying Suit. Wilbur Rounding Franks, head of RCAF medical research, invented a pressure suit that eliminated the flaws that plagued earlier oxygen-mask designs. It allowed pilots to carry out high-speed manoeuvres without losing consciousness. G-suit information was freely distributed to Canada’s allies. The pressure suits worn by modern-day astronauts are based on Franks’ design.

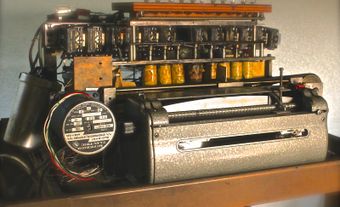

Aircraft De-icing

The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) has been involved in keeping planes ice-free since 1939. As aircraft began flying at ever-higher altitudes, icing became a problem, even in tropical regions. Over the decades, the NRC has become a world leader in detecting and combatting aviation icing, which can impact a flight’s performance. The NRC is a partner in the Global Aerospace Centre of Icing and Environmental Research (GLACIER) in Thompson, Manitoba. The NRC has been at the forefront of work involving an isokinetic probe (IKP) for NASA and the aerospace industry, research on high-altitude ice crystals (HAICs) and high ice water content (HIWC), development of the particle detection probe (PDP) and the ultrasound ice accretion sensor (UIAS) and upgrading of the altitude icing wind tunnel.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom