Contemporary Indigenous art is that which has been produced by Indigenous peoples between around 1945 to the present. Since that time, two major schools of Indigenous art have dominated the contemporary scene in Canada: Northwest Coast Indigenous Art and the Woodland school of Legend Painters. As well, a more widely scattered group of artists work independently in the context of mainstream Western art and may be described as internationalist in scope and intent. Contemporary Inuit art has evolved in parallel with contemporary Indigenous art, producing celebrated artists like Zacharias Kunuk and Annie Pootoogook. (See also Important Indigenous Artists in Canada and History of Indigenous Art in Canada.)

The Northwest Coast Renaissance

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, what some have termed a renaissance of Northwest Coast art in British Columbia occurred with the appearance in abundance of traditional forms of woodcarving, metalwork, painting, prints and textiles at first among the northern nations (Haida, Tsimshian, and Kwakwaka’wakw) and more recently among the southerly Nuu-chah-nulth and the Central Coast Salish.

Traditional artwork continues to be produced for use within still vital or newly revitalized Indigenous communities. This is the case in British Columbia, where the carving of totem poles, masks, and other traditional genres has increased since the lifting of the potlatch ban by the Canadian government in 1951. (See also Indian Act.) That infamous 1884 Federal Bill 87 had prohibited performance of the potlatch, an all-important social and religious feast that required a host of artworks for the dramatic re-enactments of oral history and traditions. Recently, West Coast artists such as Tony Hunt, Robert Davidson and the late Haida artist Bill Reid (1920-98), among many others, have worked within the framework of traditional Northwest Coast art styles and imagery. This tradition that had been kept alive during the potlatch ban by such notable figures as Haida Charles Edenshaw (1839-1920), Willie Seaweed (1873-1967) and Mungo Martin (1879/82-1962).

Contemporary work produced on the west coast continues to be decidedly traditional in orientation. Artists may deviate radically from traditional imagery, forms, and composition, but their work is nevertheless produced within an established range of visual elements and motifs known as the "classic style" of Northwest Coast art. This style reached its most characteristic development among the Haida, Tsimshian and Tlingit artists in the 19th century. Contemporary art is produced on the coast today for use in First Nations villages, but more often such traditional items as masks, rattles, boxes, bowls, textiles and jewellery are adapted to Euro-Canadian techniques, materials, and functions for sale in Indigenous art shops. During his lifetime, Bill Reid best exemplified the adaptation of West Coast Indigenous traditions to contemporary purposes.

First known for his silver and gold jewellery—bracelets, rings, and brooches engraved with Haida crests such as Bear, Raven, Frog, and Killer Whale—Bill Reid became recognized nationally and internationally for his monumental public sculpture. His large wood-carved "Raven Discovering Mankind in a Clamshell" (1983), for example, stands in the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology; a large bronze,"Killer Whale," (1984) is a centrepiece of the Vancouver Aquarium in Stanley Park; and his most famous "Spirit of Haida-Gwaii" (1991) is located at the Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C. This last monumental sculpture, measuring some 6 metres in length by 4.3 metres in height, depicts Haida mythic animals on a spiritual canoe voyage. With its black patina, the sculpture resembles argillite, the traditional stone of 19th century Haida carvers. The production of this work for the Canadian embassy was temporarily halted by Reid as a protest against commercial logging in the primeval coastal rainforest of Haida Gwaii. Reid's protest illustrates the increasing frequency with which Indigenous artists in Canada have moved toward sociopolitical activism, signifying not only a shift toward new functions for Indigenous art, but also increasing participation in the democratic processes of Canadian society at large. (See also Indigenous Political Organization and Activism in Canada and Indigenous Women Activists in Canada.)

The Woodland School

The Woodland school (sometimes referred to as the Woodlands School) gained recognition in the 1970s with the rise to fame of Norval Morrisseau, an Ojibwe artist from Northwestern Ontario. Morrisseau was a key member of Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., which was later known as the Indian Group of Seven. Most Woodland artists working from the 1970s into the 1980s were inspired and influenced by Morrisseau. As a group, they are also known as Legend Painters for their depiction of imagery taken from spiritual and mythological traditions. Independent Indigenous artists gained attention first in the 1980s. In the 1990s, they have come to dominate the contemporary art scene. Many of them are now ranked among the leading visual artists working in Canada today.

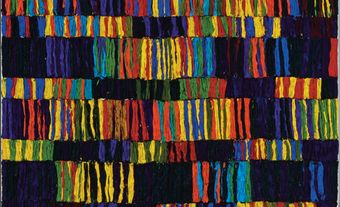

The work of the late Norval Morrisseau and related Legend Painters such as Jackson Beardy, Blake Debassige, and Carl Ray may be located approximately midway between Indigenous and Euro-Canadian aesthetic traditions. Canvases, sometimes very large, are executed in synthetic acrylic paints, a medium favoured as well by Euro-Canadian artists in the 1960s and 1970s.

At the same time, both the subject matter and style of these artists is inspired by traditional Algonquian pictography as found in sacred birch bark manuscripts of the Ojibwe and in the pictographs and petroglyphs of the Canadian Shield region. Morrisseau's sources included also the stained-glass windows of his childhood Catholic church and the beliefs of the Eckankar religion. These spiritual traditions appealed to his innate Ojibwe mystic vision of the world, first gleaned at the knee of his maternal grandfather, a traditional Ojibwe medicine man. This combination of both traditional Indigenous and Western arts and spirituality resulted in Morrisseau's work, and in many others of his following, an artistic expression standing between two cultures and appealing to both.

Indigenous Art enters the Mainstream

A wide network of contemporary artists of Indigenous ancestry have been producing work that is almost entirely within the Euro-Canadian and international mainstream. These artists are no longer trained in the traditional techniques of various First Nations, nor are they self-taught, as was Morrisseau. Instead, they have studied in leading art schools in Canada, the United States and Great Britain. Artists such as Carl Beam, Bob Boyer, Robert Houle, Alex Janvier, Gerald McMaster, Lawrence Paul, Edward Poitras, Jane Ash Poitras, Joane Cardinal-Schubert and Pierre Sioui are all individualists who have seen themselves as artists first, but for whom their Indigenous background is an important aspect of their identity. Even so, they take pride in their identity and see their role as artists in a traditional way; that is, they use their art to speak on behalf of their people.

Although their works are produced entirely in the Western context of art schools, galleries, dealers, critics, and museums and with the techniques, genres, and modes of expression characteristic of contemporary Western art, their focus is upon making a personal statement about any or all of the social, political, racial, and environmental issues facing both Indigenous peoples and the wider global society at large. While personal and individual in experience and expression, these artists are nevertheless informed by the spiritual and cultural values of their respective traditions.

Critique and sociopolitical activism appeal strongly to these artists. Their works question both the past and present difficult relations between Indigenous and Euro-Canadian society. In particular, they bring to the foreground, through word and image, the current world crises— ecological degradation, poverty, violence, war, and AIDS—that all of humanity face.

The late Carl Beam, of Ojibwe heritage from West Bay, Manitoulin Island, in Ontario, exemplified the independent contemporary Canadian artist of Indigenous background. Rejecting the label "Indian artist," his multimedia works spoke with Indigenous values to the wider Canadian and international audience of global issues of survival and human injustice. Working in a decidedly postmodernist vein, his work collapsed forms and images derived from the world's art history into one space-time frame.

In one work, Semiotica I (1985-89), Beam combined images of a soaring eagle, pre-eminent symbol of Indigenous spirituality, with those of a Cape Kennedy spacecraft ready for launching, a traffic light and a parking meter. Observers are meant to draw their own conclusions from the work, a feat best accomplished when one becomes familiar with the whole of this artist's creative output. Contemporary work by Indigenous artists is expanding rapidly into performance art, new media, ivideo, and installation projects. Vancouver-based Ojibwe artist Rebecca Belmore, who was the first female Indigenous artist to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale (2005) and was one of the winners of the 2013 Governor General ‘s Award in Visual and Media Arts, has undertaken fierce, iconoclastic public performances on themes like the disappearance of Indigenous women from the streets of Vancouver (Vigil, 2002). Belmore has also mounted elaborate video installations, typically using herself as the chief performer, addressing metaphorically charged themes like water (Fountain, 2005), and has created countless sculptures and photographs that address a wide array of Indigenous themes.

An artist of Cree and Irish ancestry, Kent Monkman (born 1965) has staged elaborate pageants in bright, feather costumes that look like a cross between a drag queen contest and a religious ritual, painted historical panoramas in the 19thcentury Hudson River School style, and made videos, all deploying his perverse and funny alter-ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle.

Born in Fort St. John, British Columbia in 1970 of Cree and Swiss ancestry, Brian Jungen, whose work has received major surveys at the Tate Modern in London and the Vancouver Art Gallery and who is a recent recipient of the Gershon Iskowitz prize at the Art Gallery of Ontario, uses the ordinary objects of popular culture and everyday life to create intensely crafted works that address Indigenous issues in the larger context of global consumer culture. In Prototypes of New Understanding, for instance, Jungen sewed parts of Nike Air Jordans into Northwest Coast style masks. In Shapeshifter (2002) and Cetology (2003), Jungen built massive (to scale) whale skeletons out of white plastic lawn chairs.

As among other Canadian artists of the late 20th and early 21st century, those of Indigenous background continue to produce works that express concern for society as a whole. As Indigenous people, these artists help bring authenticity, conviction, and often direct personal experience to the empowerment of their visual representations.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom