Art asks the viewer to move beyond what is necessary to what is possible, meaningful and spiritual. The oldest Indigenous art found in Canada are intricate stone carvings over 5,000 years old. Among the thousands working since the last ice age to today are these remarkable artists who have made significant contributions. (See also History of Indigenous Art in Canada and Contemporary Indigenous Art in Canada.)

1. Bill Reid (born 12 January 1920; died 13 March 1991; Haida)

Reid studied art in Toronto and London, England before returning to Vancouver to create large sculptures that celebrated Haida culture. His work earned international respect and several high-profile commissions. His most notable pieces were the four-tonne Raven and the First Humans done for the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology; a whale called The Chief of the Undersea World done for the Vancouver Aquarium; and Spirit of Haida Gwaii, majestic canoeists that now grace the grand entry of the Canadian embassy in Washington. His sculptures renewed interest in Northwest Pacific Coast Indigenous art and culture and his political advocacy brought attention to Indigenous issues.

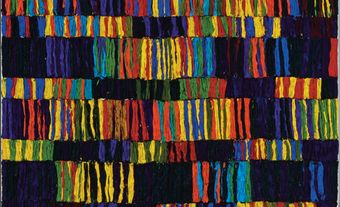

2. Daphne Odjig (born 11 September 1919; died 1 October 2016; Anishinaabe)

Beginning in the 1960s, Odjig’s expressive, richly colourful paintings spoke to Indigenous history, spirituality, and the beauty of nature. In the 1970s, Odjig’s large murals became increasingly popular, and her collage entitled Earth Mother was prominently displayed at the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 70 in Japan. In 1974, she opened the New Warehouse Gallery, the first Indigenous-owned art gallery in Canada. It became a meeting place for emerging Indigenous artists who, with Odjig, were called The Indian Group of Seven. They advanced respect for contemporary Indigenous art. Her later work became even more experimental and distinct in its representations of Anishinaabe stories and legends.

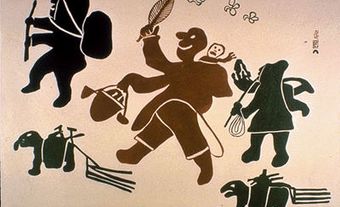

3. Norval Morrisseau (born 14 March 1932; died 4 December 2007; Anishinaabe)

Morrisseau was a member of the Indian Group of Seven and creator of the Woodlands School artistic genre. He used bright colours to express traditional Indigenous stories and spirituality. His 1962 exhibition at Toronto’s Pollock Gallery made Morrisseau the first artist of First Nations ancestry to break through the Canadian professional white-art barrier. Morrisseau became a national figure while advancing interest in Indigenous art. His work joined that of eight other Indigenous artists at the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 67. His 1968 Windigo and Other Tales of the Ojibways portrayed Anishinaabe legends and increased the popularity of his work that remains permanently displayed in prominent art galleries across Canada.

4. Frieda Diesing (born 2 June 1925; died December 2002; Haida)

Diesing brought a pride in her Haida culture to her creation of jewellery, blankets, and masks. At age 42, she carved her first totem pole that, in 1974, was erected in Prince Rupert, where she had been born. She went on to carve more totem poles while instructing others how to carve. By the 1980s, her totem poles were standing tall in public outdoor places and in galleries and museums across Canada. Her stunning exhibition, Legacy – Tradition and Innovation in Northwest Coast Indian Art, toured the world, teaching all who marvelled at the power and beauty of her art about the rich Haida culture and history.

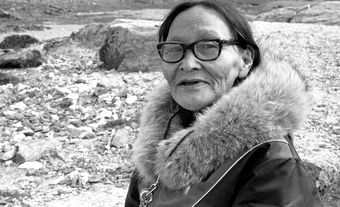

5. Kenojuak Ashevak (born 3 October; died 8 January 2013; Inuk)

Ashevak’s early work portrayed etchings of animals and birds in vibrant colours and forms that seemed to blend into nature and each other. Her work gained immediate attention in the late 1950s and increased interest in the North and in Indigenous art. She was also a sculptor and designer of blankets and stained-glass windows. She created a large and vibrant mural that was displayed at the 1970 World’s Fair in Japan. Her Enchanted Owl(1960) was used on a stamp to celebrate the Northwest Territories’ centennial. Ashevak’s later work became more stylized and challenging, such as the dog-man-dragon represented in the widely respected Dog Mother Shaman Transformation. A founding member of Cape Dorset’s famed printmaking co-op, Ashevak was the subject of one of Historica Canada’s Heritage Minutes in 2016.

6. Allen Sapp (born 2 January 1929; died 29 December 2015; Cree)

After years of struggling to promote interest in his art, a 1969 showing at Saskatoon’s Mendel Art Gallery sparked a national then international appreciation for the manner in which Sapp’s oil and acrylic paintings reflected a reverence for Indigenous spirituality, traditions and the land. His work speaks of family, community, pride and the sadness of loss. Sapp and his art became the subject of books and films. He was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, earned the Saskatchewan Award of Merit and the Order of Canada; all of which reflected his significance in bringing Indigenous stories to a wide and appreciative audience.

7. Kent Monkman (born 13 November; Cree)

Monkman’s work depicts serious issues such as the settlers’ contact with Indigenous peoples, attacks on Indigenous traditions and the depiction of homosexuality, but always in ironic, satirical ways. Large canvasses reveal startling colour and multiple characters in a style reminiscent of 19th-century Western romantic art. For example, Monkman presented an exhibit in 2017 that included The Daddies. It harkened to the Robert Harris portrait of the Fathers of Confederation but had them in a circle leering at a naked Indigenous woman. Monkman’s work is displayed in Canadian galleries and internationally. He has earned many awards and is respected as one of the most important artists of his generation.

8. Christi Belcourt (born September 1966; Métis)

While primarily a painter, Belcourt also works with copper, clay, birch bark and other natural materials to create art that speaks to Indigenous traditions, spirituality, knowledge and respect for the earth. Her work is displayed at galleries across Canada. Her stunning stained glass piece, Giniigaaniimenaaning (Looking Ahead),that commemorates residential school survivors is permanently installed at the main entrance at the Parliament Building’s Centre Block. Her blending art with political activism was seen in 2012, when she began Walking With Our Sisters, which involved 1,500 artists in an exhibit that toured the world for over seven years, bringing attention to the lives of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

9. Jane Ash Poitras (born 11 October 1951; Cree)

Poitras earned a Bachelor of Science degree, but then devoted her life to art and studied printmaking, painting and sculpture at Columbia University. Her work combines Indigenous history and cultures with contemporary Western artistic styles such as combining photographs with text. A Sacred Prayer for a Sacred Island (1991), for example, presents an eagle feather with a five-dollar bill, blending the sacred Indigenous symbol with the Canadian government’s annual treaty annuity. She remarked, “I didn’t intend to be political. But somebody has to be the troublemaker and it might as well be me.” Her work is enjoyed at galleries across Canada and around the world.

10. Alan Syliboy (born 8 September 1952; Mi'kmaq)

Syliboy’s nationally and internationally respected art, music, books, and films express his search for family and identity within the celebration of Mi'kmaq traditions and spiritualism. In 2018, Syliboy presented a mixed-media exhibit inspired by the Mi’kmaq legend of Thunder teaching his son, Little Thunder, that he must accept his responsibilities. Expanding on the exhibit, he illustrated and wrote the book, The Thundermaker, in both English and Mi'kmaq. The bestselling book was shortlisted for First Nations Reads. Syliboy was presented with the Queens Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom