Île Sainte-Hélène Fort is a former military site built by the British. It is located on the St. Lawrence River, across from downtown Montreal.

The military structure includes an arsenal, armory, barracks and powder magazine. Originally, this fortified complex served as a warehouse for military goods. Some buildings are located inside the fortified enclosure, others outside. It is not a classic fort, but rather a military supply site.

History of the Site before the Conquest

Originally the island was a natural site visited by the Indigenous people. Archaeological research has revealed traces of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and the Algonquians. In May 1611, Samuel de Champlain named the island Saincte Elaine, likely in honour of his wife Hélène Boullé.

In 1635, the island belonged to Charles Lauzon, son of Jean de Lauzon, who later became Governor of New-France in 1651. In 1665, it was transferred to the seigneury of Longueuil, fief of Charles Le Moyne, which was raised to the rank of barony 1700 (the title of baron still exists).

During the Conquest, the French hastily built rudimentary fortifications to counter the British advance. These were structures made of earth for their artillery and entrenchments. They were the last military works erected by the French before their defeat.

When the British armies arrived, a group of senior officers proposed a last stand on Île Sainte-Hélène, but Governor Vaudreuil decided to capitulate to avoid unnecessary deaths. The island and this historic episode generated the legend that the Chevalier de Lévis burned his flags there so as not to have to surrender them to the British. In reality, French troops burned the flags wherever they were found around Montreal. (See Capitulation of Montreal, 1760.)

Construction of Permanent Fortifications Under British Rule

The British began building two lookout towers on the island beginning in 1807.

After the War of 1812, British authorities feared another American invasion. In 1818, they eventually purchased Île Sainte-Hélène from William Grant, Baron of Longueil, with the aim of building a fort to reinforce the military defense system of the British North American colonies. This plan would form part of a major network of fortifications along the St. Lawrence and Richelieu rivers, invasion routes often used by the Americans. The project to build the fort on Île Sainte-Hélène was also intended to replace Montreal’s old citadel and military installations. The British army had already begun to demolish Montreal’s old French fortifications. However, the island was not really suited to protecting Montreal. To defend the colony, the British turned instead to Quebec City and the defences along the Richelieu. (See Quebec Citadel National Historic Site of Canada.)

The purpose of the fortified complex on Île Sainte-Hélène become to store military equipment and to serve as a supply center between Quebec City and Great Lakes.

Did you know?

Montreal still uses the fort for the supply function today. In fact, Garnison Montréal, also known as Garnison Longue-Pointe, located in the east end of Montreal, serves as military storage for the Canadian Armed Forces.

The Duke of Wellington, who had defeated Napoleon and was Master General of British equipment at the time, commissioned Elias Walker Durnford, an officer and military engineer, to build the fortified storage complex.

The fort was constructed between 1820 and 1824, in the shape of a crescent. The military buildings were constructed using breccia, a local reddish-brown stone that is harder than granite.

The fortified enclosure spans five acres, and the walls are approximately two meters thick. Originally, it included the arsenal, which is an ammunition depot, as well as an armory, barracks for up to 274 soldiers, warehouses, loopholes, and cannons. A powder magazine with a capacity of 5,000 barrels of gunpowder was located outside the enclosure. Blockhouses ― two-story wooden observations posts ― were also built on the island.

Did you know?

In the mid 19th century, Canada feared the threat of American invasion due to territorial tensions with the United States and Fenian raids.

The Fort’s Military Use After 1867

After Confederation, the British army surrendered the military installations to the new Canadian government and left the island in 1870.

During the Second World War, the island’s military facilities held prisoners of war. In the 1970s, during the October Crisis, Île Sainte-Hélène, still partly owned by the Department of National Defense, was the place from which members of the Front de libération du Québec left for Cuba in exchange for the release of British diplomat James Cross.

It wasn’t until 1992 that the Federal Government ceded the entire facility to the city of Montreal, ending the island’s military function.

Cultural and Recreational Use

Shortly after the departure of the British army in 1870, Île Sainte-Hélène began to be used for recreation. In 1874, the half of the island without military facilities became the first landscaped municipal park managed by the city of Montreal. The army maintained the part of the island with the arsenal to carry out military exercises. Therefore, the island became a boating and picnic destination.

Recreational tourism activities are a continuation of Montreal’s urban development that began in the 1930s with the work of urban planner and landscape architect Frederick Gage Todd. In 1930, the inauguration of the Pont du Havre (now the Pont Jacques-Cartier) encouraged the growth of these activities.

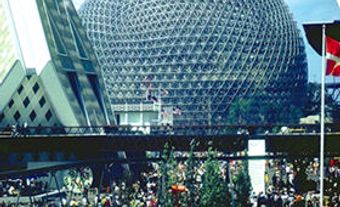

After the Second World War, recreation and tourism activities were made available to the general public. The island played host to the Expo ‘67 which coincided with the arrival of the Montreal Metro.

In 1955, David Macdonald Stewart, a wealthy industrialist who had made his fortune in tobacco, founded the Musée Militaire de Montréal (Montreal Military Museum) on the island. In 1965, the museum was renamed Musée Militaire et Maritime (Military and Maritime Museum), then Musée de l’Île Sainte-Hélène from 1976 to 1983 and in 1984, Musée David M. Stewart. Initially, the museum was housed in one of the fort’s blockhouses, then in the arsenal.

In 1957, Jeanine Beaubien founded the La Poudrière theatre in the powder magazine. This small theatre had 180 seats. Plays were performed in French and English, as well as in other languages.

This was the golden age of Montreal theatre, and of small theatres like Les Saltimbanques. La Poudrière theatre became a stepping stone for many of Quebec’s future great actors and actresses, including Pascal Rolin, Louise Turcot, Louise Marleau and Marcel Cabay.

In 1973, La Poudrière opened a children’s puppet theatre, founded by Michel Fréchette. A few years later, he established the puppet theatre training program at UQAM as well as the Théâtre de l'Avant-Pays. The La Poudrière theatre closed for good in 1982 due to financial difficulties.

After merging with the Musée McCord in 2013, the Musée Stewart closed its doors in 2021. A new purpose is now being sought for the arsenal’s museum facilities.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom