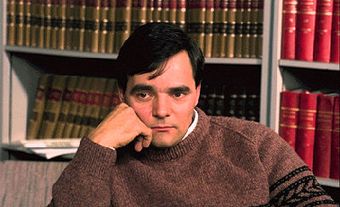

Donald Marshall Jr., Mi'kmaw leader, activist, wrongly convicted of murder (born 13 September 1953 in Sydney, NS; died 6 August 2009 in Sydney, NS). Donald Marshall’s imprisonment (1971–82) became one of the most controversial cases in the history of Canada's criminal justice system. He was the first high-profile victim of a wrongful murder conviction to have it overturned, paving the way for others such as David Milgaard and Guy Paul Morin (see David Milgaard Case; Guy Paul Morin Case). In the 1990s, Marshall was also the central figure in a significant Supreme Court of Canada case on treaty rights related to hunting and fishing.

Early Life

Donald Marshall was born on the Membertou Reserve in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the eldest of 13 children of Donald Sr. and Caroline Marshall. His father was honorary Grand Chief of the Mi’kmaq Nation.

Marshall was a rebellious youth. He got into trouble when he was sent to a non-Indigenous school. At age 15, he was expelled for striking a teacher. He then fell in with Membertou’s Shipyard Gang – teens who engaged in panhandling and petty theft. Marshall became known to police for delinquent behaviour, but not for violence. At 17, he was sentenced to four months in the county jail for giving alcohol to minors.

Seale Murder

On the night of Friday 28 May 1971 in Sydney's Wentworth Park, Donald Marshall ran into a casual acquaintance named Sandy Seale, a 17-year-old Black youth. The teenagers encountered two men, Roy Ebsary and Jimmy MacNeil. A confrontation followed in which Ebsary stabbed Seale in the stomach and slashed Marshall on the arm. Everyone fled the scene, leaving Seale bleeding on the ground. Marshall soon returned and helped summon an ambulance. Seale died in hospital the next day.

The officers of the Sydney Police Department had little experience or training in conducting a homicide investigation. They rejected an offer of assistance from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. No autopsy was performed on the victim’s body. The crime scene wasn’t secured or photographed. A cursory search of the location turned up little evidence, and no murder weapon.

Marshall volunteered to assist the police, but it wasn't until two days later that police took a formal statement. Marshall gave an account of how he and Seale had met two men who asked them for cigarettes. Marshall said the older man made racist remarks about Indigenous people and Black people before pulling a knife (see also Anti-Black Racism in Canada). Marshall gave the police descriptions of the men, but police didn’t search for the suspects. After a brief interview with Marshall, investigators decided he had stabbed Seale during an argument. They believed the cut on his arm was self-inflicted. They did not search Marshall’s home for a murder weapon.

Under questionable circumstances, police interrogated three other teenagers who had been in Wentworth Park on the night of the murder. They obtained two statements that claimed Marshall had stabbed Seale. On 4 June, police arrested Marshall and charged him with murder.

Trial and Prison

Donald Marshall went on trial in the Cape Breton County Courthouse in Sydney on 2 November 1971. He was found guilty of non-capital murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was imprisoned in the penitentiaries at Dorchester, New Brunswick, and Springhill, Nova Scotia. In October 1979, Marshall escaped from Springhill but was soon recaptured.

Throughout his time in prison, Marshall insisted on his innocence. He believed that speaking up in this way was the reason he was denied temporary passes and refused permission to attend his grandmother’s funeral. It was difficult financially for his parents to make the trips to visit him. The Marshall family received threatening and racist phone calls, and Donald Sr.’s business suffered. At one point, the family was obliged to apply for welfare. Marshall wrote letters to politicians seeking to have his case re-opened, to no avail.

Reprieve

Ten days after Donald Marshall’s conviction, Jimmy MacNeil came forward to tell the Sydney police that he had seen Roy Ebsary stab Sandy Seale. The police dismissed the evidence, considering the case closed. MacNeil's new evidence was not disclosed to Marshall's lawyer, nor to the crown prosecutor handling Marshall's appeal of his conviction. However, in February 1982, at the request of the Sydney police, the RCMP began an investigation into MacNeil's claim, as well as other new information: Ebsary had allegedly admitted to a former roommate that he had stabbed Seale. Ebsary's daughter Donna had also told a friend that she had seen her father washing what looked like blood from his knife on the night of the murder.

In addition, Marshall had sent the Nova Scotia parole board and the Sydney police copies of a letter he’d received from Ebsary, in which Ebsary said he knew Marshall was innocent. In December 1981, Ebsary had been convicted in a separate case, following another stabbing incident.

The RCMP investigation revealed serious flaws not only in the Sydney Police Department’s handling of the case, but also in the judicial proceedings. Witnesses had been intimidated by police and had perjured themselves (given false testimony). Evidence that supported Marshall’s plea of not guilty had been withheld. Even Marshall’s own defence lawyers had doubted his innocence and hadn’t sought to verify his account of the events in Wentworth Park.

Underlying the whole mismanaged case was the taint of racism. Some officers of the Sydney Police Department had been known to have prejudiced attitudes towards First Nations people. One member of the jury that convicted Marshall admitted to bigoted feelings towards people who were not white.

Questioned by RCMP investigators, three witnesses recanted the evidence they had given at Marshall’s trial. The murder weapon was found in Ebsary’s former residence. The knife still bore fibres from the clothing Seale and Marshall had been wearing the night of the stabbing. On 29 March 1982, Marshall was released on parole after having served nearly 11 years for a crime he didn’t commit. Ebsary would eventually be found guilty of manslaughter in Seale's death.

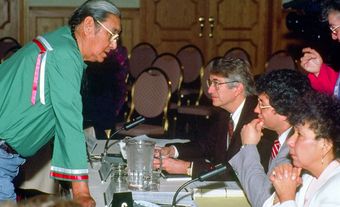

Royal Commission

In May 1983, the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia officially acquitted Marshall of Seale’s murder. But the judges absolved the Sydney police and the crown prosecutors, while holding Marshall partly responsible for his own misfortunes. A Royal Commission was appointed by a Nova Scotia order-in-council on 28 October 1986. The commission said the wrongs done to Marshall were a result of racist attitudes and also incompetence on the part of police, prosecutors and judges at every step in the process. The commissioners declared: “The criminal justice system failed Donald Marshall, Jr. at virtually every turn from his arrest and wrongful conviction for murder in 1971 up to, and even beyond, his acquittal by the Court of Appeal in 1983.”

The commissioners produced 82 recommendations that fundamentally changed the criminal justice system in Nova Scotia. For Marshall, however, the fight for justice had taken a toll on him psychologically, resulting in lifelong struggles with depression and alcoholism. Still, his case was a judicial trailblazer for other Canadians wrongly convicted of murder. It drew considerable interest from the general public, prison reform groups and organizations opposed to the reinstatement of capital punishment. Marshall was awarded a lifetime pension of $1.5 million in compensation for his suffering. (See also Marshall Inquiry.)

Treaty Rights

In August 1993, after catching and selling eels near Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Donald Marshall was convicted on charges of fishing out of season and without a licence. That began a six-year legal battle over Mi’kmaw treaty rights that went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. In a landmark ruling reached in 1999, the court upheld fishing and hunting rights that the Crown had granted the Mi’kmaq Nation in a treaty signed in the 1760–61 Peace and Friendship Treaties. The Marshall case remains an important Indigenous rights ruling affirming the right of Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqiyik and Passamaquoddy peoples to earn a "moderate" commercial livelihood from fishing and hunting, subject only to conservation requirements. Marshall, who never considered himself a political activist, said, “I wasn’t there for myself. I was there for my people.”

Death

In 2003, suffering from a chronic respiratory disease, Donald Marshall underwent a double lung transplant. His last years were troubled by poor health, domestic difficulties and a financial dispute stemming from the treaty rights case. In 2001, for example, Marshall had been promised $2-million by a group of Atlantic First Nations chiefs, in recognition of his struggle on behalf of Indigenous peoples for historic fishing and hunting rights. Six years later, Marshall's wife made it known that he had only received a small fraction of the money from the chiefs.

In August 2009, suffering from kidney failure, Marshall was admitted to hospital in Sydney, where he died, aged 55. He was buried as a First Nations hero.

Did You Know?

The records of the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall, Jr., Prosecution are now available online, thanks to the Nova Scotia Archives. The Royal Commission (also known as the Marshall Inquiry), appointed on 28 October 1986 to examine the case from initial investigation through to trial, re-investigation, and appeal, has digitized its extensive records for the public. The Commission’s seven-volume report includes 16,390 pages of transcribed testimony that record the 89 days of hearings, the words of 114 witnesses, and the context of 176 exhibits. The audio recordings of Marshall’s testimony, in Mi’kmaq, have also been made available by the Nova Scotia Archives as a historic treasure: “The collection is vitally important, both for its vindication of wrongfully-convicted Marshall Jr., and for its role in shaping the Canadian and Nova Scotian justice systems that we know today.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom