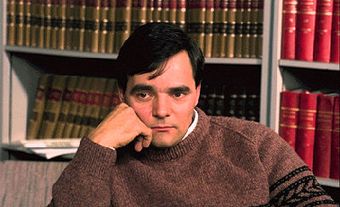

David Milgaard was a 16-year-old hippie when he was charged with the rape and murder of Saskatoon nurse Gail Miller in 1969. Milgaard's prosecution for first degree murder at age 17 became one of Canada's most notorious wrongful convictions. He was finally released in 1992 after 23 years in prison. DNA evidence exonerated him in 1997 and led to the conviction of Larry Fisher, a serial sex offender, in 1999. Milgaard received an official apology from the Saskatchewan government in 1997 and a $10 million settlement in 1999. Milgaard became an advocate for prison reform and the rights of the accused and helped establish a federal commission to investigate cases of alleged wrongful conviction.

This article contains sensitive material that may not be suitable for all audiences.

Miller Murder and Investigation

Gail Miller was raped, stabbed to death, and left in a snowbank at approximately 6:45 a.m. on 31 January 1969. Her body was discovered two hours later. Police quickly sought out known sex offenders in the area to question them, but could find no obvious leads.

That same morning, David Milgaard (born 7 July 1952 in Winnipeg) — accompanied by two friends, Ron Wilson and Nichol John — had arrived in Saskatoon en route from Regina to Calgary. The trio stopped at the home of a mutual friend, Albert “Shorty” Cadrain, around 9:30 a.m., to pick him up and continue their journey.

A month after the murder, Cadrain contacted police to report that Milgaard had acted suspiciously during the drive to Calgary. He also said that Milgaard appeared to have blood stains on his clothing that day. Within 24 hours, police located Milgaard in Winnipeg and questioned him. Milgaard denied any involvement in the murder.

Investigators then located Milgaard’s two other travelling companions, Nichol John and Ron Wilson. Their initial police statements provided a strong alibi for Milgaard; both said that they had been with him throughout the morning of the attack on Miller and that Milgaard had had nothing to do with it.

Milgaard Convicted

In May, however, investigators began hearing reports that Milgaard had entertained friends in a Regina hotel room by re-enacting the Miller murder. The police decided that John and Wilson had lied in their initial statements and brought them in to be re-interviewed. This time, the youths changed their statements, implicating Milgaard in the murder. John went so far as to state that she had even witnessed Milgaard stab the victim.

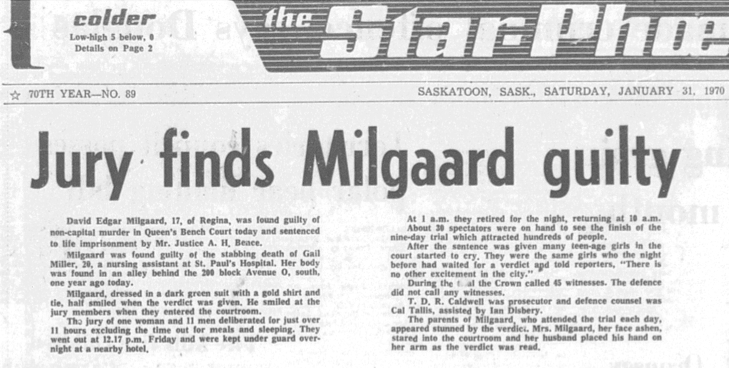

Milgaard was charged with first-degree murder on 30 May 1969. His trial commenced before a judge and jury nine months later. After the Crown had presented its case, Milgaard’s lawyer elected to call no evidence. Milgaard was convicted on 31 January 1970. He was sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for at least 10 years. Two years later, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal.

Joyce Milgaard's Campaign

Throughout Milgaard's incarceration, his mother, Joyce Milgaard, worked tirelessly to bring attention to what she was convinced was her son’s wrongful conviction. With an unerring nose for news and a fat Rolodex of media contacts, Joyce Milgaard supplied journalists with a stream of angles over the years to keep her son’s story alive and exert pressure on authorities. At one stage in her crusade, she confronted federal justice minister Kim Campbell as television cameras rolled. She also threatened to camp on the lawn of the Saskatchewan legislature.

In December 1988, David Milgaard applied for a federal review of his case under section 690 of the Criminal Code. The provision permits the minister of justice, after considering fresh evidence, to ask a senior appeal court to review a conviction or to hold a new trial. In February 1991, Justice Minister Campbell dismissed the application. Six months later, a second application — this one focusing attention on the potential guilt of Larry Fisher, a known offender — was accepted by Campbell. In a highly unusual development, the federal government referred the Milgaard application straight to the Supreme Court of Canada, the highest court in the country.

Supreme Court

The fresh evidence assembled on Milgaard’s behalf included a recantation by witness Ron Wilson. Wilson said that he had been coming down from a drug high at the time of his second police interview; he thought the police would release him to the street where he could obtain more drugs if he gave them what they wanted.

Another key piece of fresh evidence involved a 1970 confession by a local sex offender, Larry Fisher. Fisher had admitted to committing six sexual assaults, including four in the same area of Saskatoon where Gail Miller was killed, raising the very real possibility that she was another of his victims.

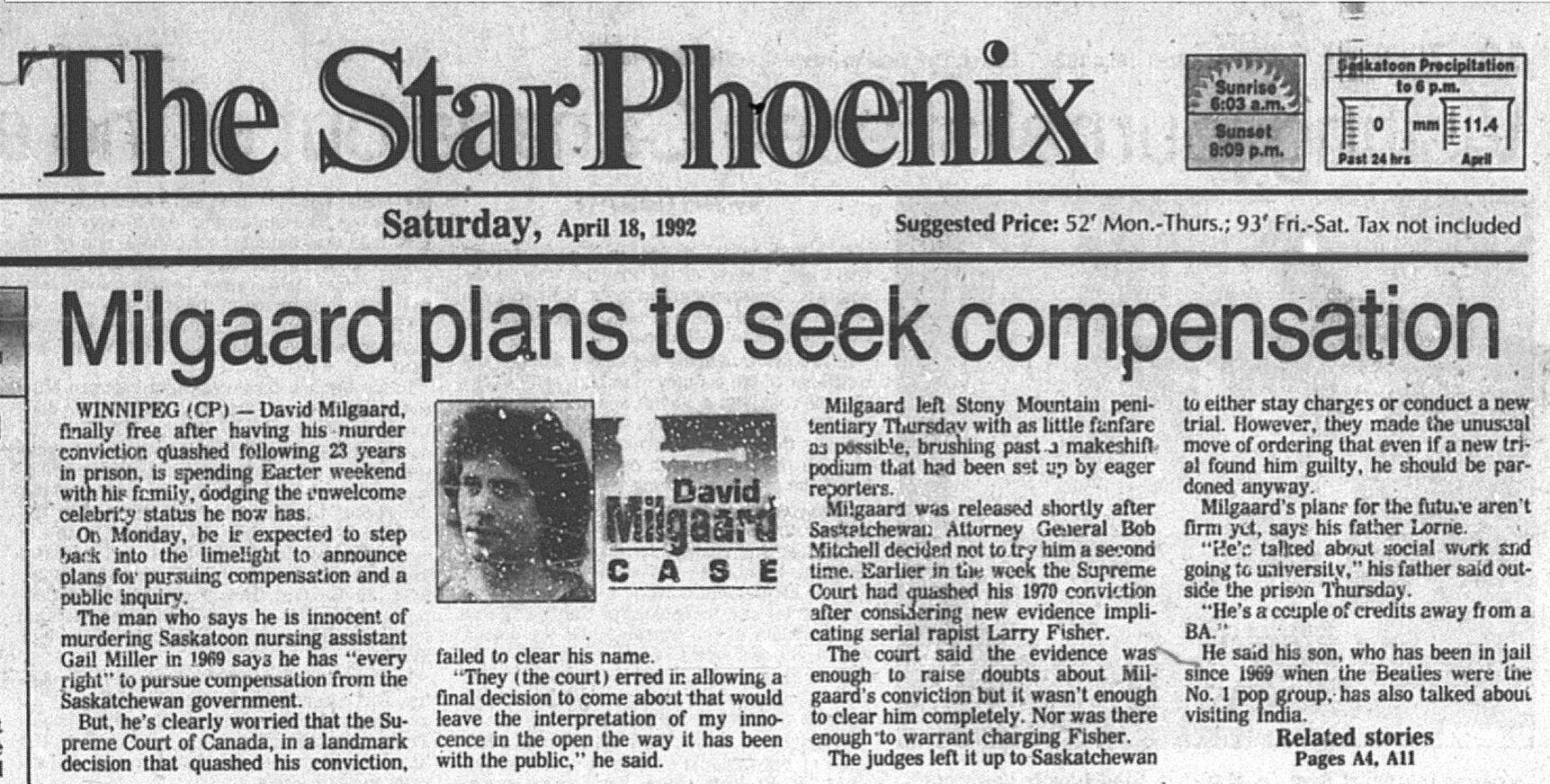

The Supreme Court heard the fresh evidence in 1992. It issued a recommendation to the department of justice that Milgaard’s conviction be quashed and a new trial held. However, this decision disappointed Milgaard and his supporters, because the court concluded that his trial had been fair and was not marred by police wrongdoing.

Milgaard Freed

The federal government adhered to the court’s recommendation. However, two days later, the attorney general of Saskatchewan decided to enter a stay of proceedings (a halt in the legal process) instead of retrying the case. That meant Milgaard would be freed immediately. Still, he was unsatisfied because the outcome would also make it difficult for him to obtain financial compensation. The province also angered Milgaard’s supporters by refusing to call an inquiry, to probe what had gone wrong in his case.

Milgaard's Lawsuit

In 1993, David Milgaard filed a lawsuit against Saskatchewan justice officials and police alleging rampant wrongdoing and a cover-up. The legal proceeding moved at a glacial pace, prompting Milgaard to contact James Lockyer, a lawyer with the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted (AIDWYC), in 1996. It was known that semen samples had been found on Miller’s clothing and retained by the Crown. AIDWYC pressed for them to be tested for DNA in hopes of definitively clearing Milgaard’s name.

It took years of legal wrangling for Lockyer to obtain the samples and arrange for them to be tested at a lab in the United Kingdom. The results ultimately excluded Milgaard as the man who had murdered Miller. Instead, the DNA results pointed directly toward Larry Fisher as the perpetrator.

AIDWYC Investigation

Through its own investigation, AIDWYC learned that in 1970, Fisher had been well known to police. Furthermore, at the time of the Miller murder, he was renting a basement apartment in the same home where Albert Cadrain lived.

Lockyer and AIDWYC also learned of Fisher’s 1970 confession to several rapes in the Saskatoon area, for which he had served a 10-year prison sentence. Released in 1980, Fisher had been arrested within weeks for a new sexual assault, which led to him being sentenced to another 10-year term.

With new rules governing disclosure of evidence having come into effect across the country, Milgaard’s defence team were also able to obtain documents showing that in August 1980, Fisher’s ex-wife Linda had contacted Saskatoon police to say that she suspected he had murdered Gail Miller. On the day of the Miller murder, Linda Fisher said, a paring knife had gone missing from their kitchen. She told police that her ex-husband also appeared shocked and flustered when she confronted him that day to accuse him of committing the attack.

Larry Fisher Conviction

When Linda Fisher contacted police, Milgaard was locked in prison for the crime. Police never followed up on the tip. Fisher was arrested on 25 July 1997. With DNA evidence linking him to the victim, he was convicted in 1999 of murdering Gail Miller. He was sentenced to life in prison and died in 2015 at the age of 65.

Compensation and Inquiry

Meanwhile, a public and media furor had continued to swirl around the Milgaard case. Under intense pressure, the Saskatchewan government appointed retired Quebec Superior Court justice Alan Gold to negotiate a compensation package for Milgaard. His recommendation of a $10-million settlement was accepted by the government in May 1999.

In 2004, the province also succumbed to demands for an inquiry, appointing Justice Edward P. MacCallum of the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench to preside over it. MacCallum released a series of recommendations and findings in 2008, many of them relating to the retention and disclosure of evidence. In a key conclusion, he found that a Saskatoon police polygrapher who had re-interviewed John and Wilson for a lie detector test, had exerted unacceptable pressure on them, causing them to change their stories and effectively seal Milgaard’s fate with false testimony. The Saskatoon Police Service officially apologized to Milgaard in December 2006.

Personal Life and Later Years

During his 23 years behind bars, Milgaard suffered enormous psychological stress. He was physically and sexually assaulted on numerous occasions and attempted suicide several times. In the years following his exoneration, he spoke freely about his suffering. He became an advocate for prison reform and the rights of the accused. He worked with the federal department of justice to establish a commission to investigate cases of alleged wrongful conviction.

Milgaard married and had two children. He and his family lived in Cochrane, Alberta. Joyce Milgaard died in a Winnipeg care home in 2020 at age 89. David Milgaard died of pneumonia at a Calgary hospital on 15 May 2022 at the age of 69. Following his death, psychologist Dr. Patrick Baillie, who testified at Milgaard’s wrongful conviction inquiry in 2006, told CBC News that Milgaard “wanted to live life to the fullest with the time that was available to him and not carry a grudge. His life was always defined by something he didn't do and he wanted the opportunity to define his life on the basis of the things that were important to him." Lawyer Greg Rodin, who became a friend of Milgaard’s, called him a "loving, caring and gentle person."

In Popular Culture

Carl Karp and Cecil Rosner’s When Justice Fails: The David Milgaard Story, was published in 1991. In 1992, Global TV broadcast the documentary The David Milgaard Story, directed by Vic Sarin. Tragically Hip singer-songwriter Gord Downie wrote that “Wheat Kings,” from the album Fully Completely (1992), is “about David Milgaard and his faith in himself. And about his mother, Joyce, and her absolute faith in her son’s innocence.”

The TV movie Hard Time: The David Milgaard Story, starring Ian Tracey as David and Gabrielle Rose as Joyce, aired in 1999 and won six Gemini Awards, including Best TV Movie or Dramatic Mini-Series. Joyce Milgaard’s A Mother’s Story: My Battle to Free Davied Milgaard, co-written with Peter Edwards, was also published in 1999. Comics artist David Collier told David Milgaard’s story in the graphic novel Surviving Saskatoon (2000).

See also Wrongful Convictions.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom