The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC)/Radio-Canada is one of the world's major publicly owned broadcasters. A crown corporation founded in 1936, it operates national and regional radio and television networks in English (CBC) and French (Radio-Canada). It broadcasts locally produced programs in English and eight Indigenous languages for people in the far North. It also runs a multilingual shortwave service for listeners overseas and provides closed captioning for the deaf. It gets nearly 60 per cent of its current funding from federal grants. It also draws revenue from sponsorship, advertising and the sale of programs to other countries. It is responsible to Parliament for its conduct. But the government has no control in the CBC’s day-to-day operations. For nearly 100 years, it has provided Canadians with a broad range of programming. Its critics continue to call for the CBC to be defunded and for the playing field for all broadcasters to be levelled.

Organization and Operation

CBC/Radio-Canada’s programming is broadcast on the 88 radio stations, 27 TV stations and one digital-only station that the broadcaster operated across Canada as of February 2024. Canadian content makes up over 80 per cent of prime-time schedules on both TV and radio. The radio service airs 99 per cent Canadian content over the full course of its broadcast day.

As of 2011, 8,600 people were employed by the broadcaster. By 2024, it had roughly 6,600 employees and around 2,800 contract workers.

CBC Presidents

|

1936–39 |

|

|

René Morin |

1940–44 |

|

Howard B. Chase |

1944–45 |

|

1945–58 |

|

|

1958–67 |

|

|

George Davidson |

1968–72 |

|

Laurent Picard |

1972–75 |

|

A.W. Johnson |

1975–82 |

|

1982–89 |

|

|

William T. Armstrong |

1989 |

|

Gerard Veilleux |

1989–94 |

|

Anthony S. Manera |

1994–95 |

|

1995–99 |

|

|

Robert Rabinovitch |

1999–2007 |

|

Hubert Lacroix |

2008–18 |

|

Catherine Tait |

2018–present |

Founding of the CBC/Radio-Canada

The CBC/Radio-Canada was created as a crown corporation on 2 November 1936. This followed two earlier experiments with public broadcast ownership in Canada. During the 1920s, the Canadian National Railways (CNR) developed a radio network. It had stations in Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, Moncton and Vancouver. Its schedule included concerts, comic opera, school broadcasts and historical drama. However, by the end of 1929 it was providing only three hours of programming a week.

Together with the example of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the CNR radio stations helped make the merits of public ownership more apparent to the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting. It was appointed by Prime Minister Mackenzie King on 6 December 1928. The chairman was Sir John Aird. The privately owned Canadian stations were beginning to fall into American hands. They also seemed unable to provide an adequate alternative to the programming that was flooding in from the United States.

The moving force within the Aird Commission was Charles Bowman, editor of the Ottawa Citizen. He was convinced that public ownership of broadcasting was needed to keep Canada from being overwhelmed by American culture. The Aird Commission heard submissions from across the country. It also visited other broadcasting systems. It submitted its report on 11 September 1929, less than two months before the stock market crashed. (See also Great Depression in Canada.) It recommended the creation of a national broadcasting company with the status and duties of a public utility to develop a service capable of “fostering a national spirit and interpreting national citizenship.” It also called for the private stations to be eliminated, with compensation.

Because of the economic crisis, consideration of the Aird Report was delayed. This allowed some of the more powerful private stations and their lobbying agency, the Canadian Association of Broadcasters, to launch a campaign against it. But the report’s basic principles were defended by the Canadian Radio League (CRL). It was an informal voluntary organization set up in Ottawa by Alan Plaunt and Graham Spry in the fall of 1930. They prepared pamphlets stating the case for public ownership. They recruited other organizations and representatives from business, banking, trade unions, the farming community and educational institutions. They also sent a formal delegation to meet the minister of marine and fisheries, who was responsible for licensing radio stations at the time.

Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC)

The newly elected Conservative government of R.B. Bennett responded to the appeals of the CRL by passing the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Act (1932). It established a publicly owned Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC). Its mandate was to provide programs and extend coverage to all settled parts of the country.

The CRBC took over the radio facilities owned and set up by Canadian National Railways. The CRBC began to broadcast in English and French under commissioners Thomas Maher, Hector Charlesworth and Lieutenant Colonel W. Arthur Steel. The private stations, whose fate was left in the commission's hands, did not co-operate fully. But they did help to get some CRBC programs aired nationally. Nonetheless, the CRBC allowed them to continue and even expand. In the end, most of them outlived the commission itself.

The CRBC suffered from underfunding, an uncertain mandate, inappropriate administrative arrangements and a series of tactless political broadcasts. But due to further lobbying by the CRL, the Liberal government of Mackenzie King decided to replace it with a stronger public agency rather than abandon broadcasting to the private sector.

Canadian Broadcasting Act (1936) and Early Growth

A new Canadian Broadcasting Act in 1936 created the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC)/Radio-Canada as a crown corporation. Compared to the CRBC, the CBC/Radio-Canada was better organized and less vulnerable to political pressure. It also had more assured funding via a $2.50 licence fee on receiving sets. The corporation assumed the assets, liabilities and main functions of the CRBC. These included regulating the private stations and providing homegrown programming for all Canadians.

From 1936 to 1958, the CBC/Radio-Canada was headed by a board of governors. It comprised nine unsalaried members from the various regions of Canada. The board was responsible for drafting general policy and for regulating the private stations. Its first chairman was Leonard W. Brockington, a noted lawyer from Winnipeg. In 1939, he was succeeded by René Morin.

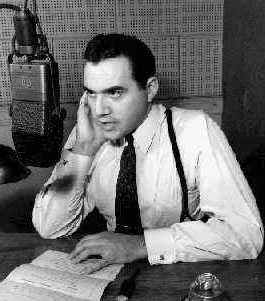

In 1944, the Broadcasting Act was amended to allow for the appointment of a full-time salaried chairman for a term of three years. On 14 November 1945, A. Davidson Dunton, who had previously served as general manager of the Wartime Information Board, was appointed to the position and served as chairman until 1 July 1958.

The board was also responsible for appointing a general manager and an assistant general manager. They oversee the day-to-day operations of the corporation. The first general manager was Gladstone Murray. He had been director of public relations for the BBC.

The CBC/Radio-Canada began operations with eight stations of its own and 16 privately owned affiliates. A technical survey revealed that this network provided service for only half of Canada's 11 million people, and mainly only in urban areas. It also confirmed that people in major cities suffered from constant interference from high-powered American stations. To fix this, 50-kW transmitters were built in Montreal and Toronto in 1937. This increased service to about 76 per cent of the population.

The same year, the CBC/Radio-Canada helped organize a North American conference in Havana, Cuba. Canada was allocated six clear channels for stations with 50 kW or more, eight clear channels for stations from 0.25 to 50 kW, and shared use of 41 regional and six local channels. To reach outlying areas, the broadcaster added 50-kW transmitters in Saskatchewan and the Maritimes in 1939. It also began building low-power relay transmitters in BC, northern Ontario and parts of New Brunswick. After the war, 50-kW stations were built in Manitoba and Alberta. The power of CJBC, the flagship station in Toronto, was increased to the same wattage.

Early Programming

The development of programming proceeded more slowly than the extension of service coverage. At first, entertainment, music and talk programs produced in the US and the UK were used heavily.

Following a program survey to determine the extent and location of Canadian talent, the CBC slowly created its own distinctive service. This included variety programs such as The Happy Gang; regional farm broadcasts and Harry Boyle's National Farm Radio Forum (for what was still a predominantly rural nation); women's interests programs such as Femina, as well as daily morning talks by a network of women commentators; sports broadcasts, including NHL hockey on Saturday nights with Foster Hewitt (see Hockey Night in Canada); children's programs such as Just Mary with Mary Grannan; and extensive coverage of events such as the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1937 and the royal tour of Canada in 1939. A separate French-language network was created. Program production was decentralized into five regions: BC, the Prairies provinces, Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, the CBC/Radio-Canada created an Overseas Service. It relayed the reports of war correspondents. On 1 January 1941, the broadcaster ended its reliance on news bulletins prepared by the Canadian Press. It created its own News Service under chief editor Dan McArthur. Through its national newscast — which was read by Charles Jennings (father of long-time ABC news anchor Peter Jennings) and later by Lorne Greene (the famous “Voice of Doom”) — the CBC News Service quickly built a reputation for impartiality and integrity.

During the war, the CBC also established Radio-Collège in Quebec and began its school music broadcasts (1942). In 1944, the broadcaster's English-language network was divided into the Dominion network (one CBC station and 34 affiliates) and the Trans-Canada network (six CBC stations and 28 affiliates). At the end of the war, the CBC/Radio-Canada joined forces with the government to establish a multilingual international service in 1945. It later became Radio-Canada International. Programs were transmitted from studios on Crescent Street in Montreal to Sackville, NB, by land lines and then sent overseas by wireless.

Public affairs programming did not at first feature much on CBC Radio. Shortly before leaving as chairman, Brockington took steps to change this situation. He wrote a white paper on political and controversial broadcasting. The paper was adopted by the board of governors in July 1939. It stated that the CBC/Radio-Canada would seek to present a variety of opinions on controversial issues and would refrain from selling network time to espouse personal views.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, however, the CBC/Radio-Canada found itself under government pressure to limit the discussion of public affairs on the air. Proposals by the CBC Talks Department for a series of forums on war-related issues were rejected by general manager Murray. Instead, the CBC rebroadcast some BBC programming intended to inspire the war effort. Murray eventually approved a discussion program called Citizens All. But he demanded personal approval of speakers and subjects.

It was not until Murray was replaced by J.S. Thomson in August 1942 that the efforts of the Talks Department to promote serious discussion on matters of public concern began to bear fruit. By the end of Thomson's one-year term, the department had demonstrated the democratic role that public affairs broadcasting could fulfill. It had introduced such programs as Weekend Review, National Labour Forum, CBC Discussion Club and the popular Of Things to Come — An Inquiry into the Post-War World. Chaired by author Morley Callaghan, the latter program evolved into the popular Citizens’ Forum. It made use of listening groups and lasted into the television era.

Canadian Drama

After the war, public affairs programming was expanded. Programs on the arts, such as Critically Speaking, and drama programs also increased. In 1940, the CBC introduced Canadian Theatre of the Air. In 1944, Andrew Allan's greatly admired Stage series made its debut.

But the heyday of Canadian radio drama came during the early post-war period. A repertory company of young Canadian actors was formed. A major program was launched to train young writers. During the 1947–48 season, there were 320 radio drama productions in English, 97 per cent of which were by Canadian writers. In addition to Allan, producers such as Esse Ljungh, Rupert Caplan and Fletcher Markle led the way in North America in serious drama programming.

By this time, however, the days of radio drama were already numbered. Canadians began mounting pressure for the introduction of television. It had become available in the United States after the war. Initially, both the CBC/Radio-Canada and the federal government chose to proceed with caution in dealing with the costly new medium. Dr. Augustin Frigon had served on the Aird Commission. He was also head of the French network before replacing Thomson as general manager in 1943. In 1946, he told the parliamentary Radio Committee that “it would be a mistake to encourage the introduction of television in Canada without sufficient financial support and, therefore, taking the risk that unsatisfactory programs would, at the start, give a poor impression of this new means of communication.”

Frigon refused to be “stampeded into premature action.” Instead, the CBC/Radio-Canada and private broadcasters undertook television training at the CBC’s facilities in Montreal and Toronto.

Advent of Television

In 1947, CBC/Radio-Canada's assistant chief engineer, J. Alphonse Ouimet, issued a study called Report on Television. Ouimet had built and tried to market his own TV network in Montreal in the early 1930s. His report was a springboard for the broadcaster to begin its own TV network. Ouimet was appointed coordinator of television. He later replaced Frigon as general manager. Ouimet is arguably the single most important figure in the history of Canadian broadcasting. He deserves much of the credit for the rapid introduction and expansion of TV broadcasting in Canada. To fund its development, the government placed an excise tax on TV sets.

Television service began on CBFT Montreal on 6 September 1952. Two nights later, it debuted on CBLT in Toronto. At the time, television was available to only 26 per cent of the population. But by 1954 this had gone up to 60 per cent. Canada ranked second in the world in the production of live TV programming. CBC/Radio-Canada stations were set up in Ottawa, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Halifax. Private stations were already starting to appear in other cities.

By 1957, the English and French networks were each broadcasting up to 10 hours a day. Their coverage had grown to 85 per cent of the population. This was achieved with CBC/Radio-Canada-owned and -operated stations and privately owned affiliates.

However, the advent of television created major problems for the CBC's radio service. Creative talent and capital funds were siphoned off by the new medium. Audience share for radio programs plummeted. Commercial profits and the supply of American entertainment programs were both greatly reduced. It was to compete against local information and American pop music formats on the private stations. As a result, the radio service became increasingly demoralized and out of touch with Canadian listeners.

Radio Revolution

During the 1960s, a few steps were taken to reclaim radio audience loyalty. Some new current affairs programs were introduced. Canadian-produced drama and serious music was increased. But it was in 1970s that the CBC’s radio service underwent the revolution that made it the pride of the corporation.

In 1970, an exhaustive radio study was released. As a result, the radio service made a fundamental shift in its mandate. Resources were reallocated from the evenings (when television is the main attraction) to the mornings and afternoons. Local information programs were developed. Block program formats were devised. National news and current affairs were strengthened with the debut of programs such as This Country in the Morning and As It Happens. At the same time, the potential of FM radio was finally pursued in earnest after two decades of experimentation. In 1975, a stereo FM network was begun and commercials were eliminated on both AM and FM.

Eventually, both AM and FM coverage grew through the Accelerated Coverage Plan that began in 1974. Two networks then emerged offering distinctive program services. The AM network concentrated on news, information, light entertainment and local affairs. The FM network focused on serious music, drama, documentaries and arts and culture.

Growth of Television

CBC/Radio-Canada's TV service adapted less successfully to its own problems in this period. During the 1950s, a new generation of producers responded to the challenge of developing programs for the medium with energy, enthusiasm and great creativity. They included Ross McLean, Norman Campbell, Norman Jewison, Bob Allen, Jean-Paul Fugere, Sydney Newman and Mario Prizek. They created an impressive array of information and entertainment programs. Examples include Tabloid, G.E. Showcase, Les Plouffe, Front Page Challenge, Festival, Don Messer's Jubilee (see Don Messer), Les Idées en Marche and Cross Canada Hit Parade.

But the broadcaster’s remarkable programming options during the 1950s did not eliminate the desire of Canadians for American programs. CBC/Radio-Canada not only produced Canadian programs. It was also expected to relay popular American programs to Canadian viewers, especially in areas where American signals could not be picked up with the aid of rooftop antennas.

Eventually, with cable television and satellites, the need for the CBC to rebroadcast American programs was eliminated. By that time, however, its television service had developed a strong dependency on US programs. This process began in the late 1950s as the era of live TV gave way to the production of expensive, pre-filmed comedy and drama series. The broadcaster was soon caught in a vicious cycle. It needed to carry popular American programs to get the advertising revenue needed to produce comparable domestic programming. After the licensing of the CTV network in 1961, the CBC/Radio-Canada found that it also had to use American programs to generate audiences for its own programs through the so-called "inheritance factor."

During the 1960s, the CBC created new television dramas such as Wojeck and Quentin Durgens, M.P. There were exciting information programs such as This Hour Has Seven Days, Man Alive and The Nature of Things. There were also long-standing children's favourites such as Mr. Dressup, The Friendly Giant and Chez Hélène.

Still, the broadcaster’s continued reliance on a high number of American programs led some to accuse it of not meeting its mandate under the Broadcasting Act. Between the 1967–68 and 1973–74 fiscal years, the broadcaster responded to growing public criticism. It increased its Canadian TV content from about 52 per cent to around 68 per cent. A host of new Canadian programs were created. The included Marketplace, The Beachcombers, Performance and The Fifth Estate.

During the same period, an attempt was made to improve the balance between network and regional programming and to increase efficiency. The English network, French network and regional broadcasting systems were merged into two divisions. The English Services Division was headquartered in Toronto. The French Services Division had its headquarters in Montreal.

Further consolidation since then allowed for the Canadianization of the TV schedule. Between 1983–84 and 1985–86, for example, Canadian content was increased from 74 per cent to 77 per cent on the English television network. It also increased from 69 per cent to 79 per cent on Radio-Canada. However, crippling budget cuts by the Brian Mulroney government in the mid-1980s postponed the dream of eliminating both foreign programs and advertising on CBC/Radio-Canada's TV services.

Television Programming

Internationally recognized personalities have long been featured on CBC/Radio-Canada's TV services. Jim Carrey's first movie, Introducing…Janet (1983), was made for CBC TV. Alex Trebek hosted CBC TV’s Music Hop (1963–64) and Reach for the Top (1966–73) before becoming the host of Jeopardy! Actor Michael J. Fox began his acting career on the CBC TV programs The Magic Lie (1977) and Leo and Me (1978). One of Keanu Reeves’s first jobs was on the children’s program Going Great (1984–85). The long-running documentary series The Nature of Things (1960–), formerly hosted by David Suzuki (1979–2023), is one of Canada’s most critically acclaimed TV programs.

Over the years, the sports division of CBC TV became one of the country’s major producers of sports broadcasts in the country. Its flagship Saturday night program, Hockey Night in Canada (1952–). The country’s top-rated program for decades (it began on CBC Radio in 1931), it is Canada’s longest-running television program and the Guinness World Record holder as the longest-running TV sports program. It became so entwined with the country’s cultural fabric that the theme song became an unofficial national anthem.

As Canada's Olympic broadcaster, the CBC also carries international events. However, some groups have criticized the use of public funds to bid for one of the world's most popular sports properties.

Notable Original CBC/Radio-Canada TV Programs

|

Children’s Programs |

|

|

Maggie Muggins |

1955–62 |

|

1957–85 |

|

|

Nursery School Time |

1958–63 |

|

The Friendly Giant (see Robert Homme) |

1958–85 |

|

Chez Hélène |

1959–73 |

|

Razzle Dazzle |

1961–66 |

|

Mr. Dressup (see Ernie Coombs) |

1967–96 |

|

Sol et Gobelet (see Marc Favreau) |

1968–71 |

|

1977–92 |

|

|

Traboulidon |

1983–86 |

|

Fraggle Rock * |

1983–87 |

|

Sharon, Lois & Bram’s Elephant Show (see Sharon, Lois & Bram) |

1984–89 |

|

Owl/TV |

1985–90 |

|

The Raccoons |

1985–91 |

|

Fred Penner’s Place (see Fred Penner) |

1985–97 |

|

Under the Umbrella Tree |

1986–93 |

|

Le Club des 100 Watts |

1988–95 |

|

Babar * |

1989–92 |

|

Bo on the Go! |

2007–16 |

|

The Adventures of Napkin Man! |

2013–17 |

|

The Studio K Show |

2017– |

|

Youth Programs |

|

|

The World of Man |

1970–75 |

|

What’s New |

1972–89 |

|

1979–84 |

|

|

The Edison Twins |

1982–86 |

|

Wonderstruck |

1986–92 |

|

1987–89 |

|

|

1989–91 |

|

|

Street Cents |

1989–2006 |

|

Watatatow |

1991–2005 |

|

The Rez (see Jennifer Podemski) |

1996–98 |

|

Jonovision |

1996–2001 |

|

Edgemont |

2001–05 |

|

Family Programs |

|

|

1972–90 |

|

|

Spirit Bay |

1984–86 |

|

Danger Bay |

1985–90 |

|

Road to Avonlea * |

1990–96 |

|

Wind At My Back |

1996–2001 |

|

2007– |

|

|

Anne with an E * |

2017–19 |

|

Music/Variety Programs |

|

|

General Motors Theatre |

1952–61 |

|

The Eleanor Show (see Eleanor Collins) |

1955 |

|

Country Hoedown |

1956–65 |

|

Juliette (see Juliette) |

1956–66 |

|

Don Messer’s Jubilee (see Don Messer) |

1959–69 |

|

Singalong Jubilee |

1961–74 |

|

Music Hop |

1963–67 |

|

The Tommy Hunter Show (see Tommy Hunter) |

1965–92 |

|

Les Beaux Dimanches |

1966–2004 |

|

The Irish Rovers (see Irish Rovers) |

1971–78 |

|

Good Rockin’ Tonite |

1983–93 |

|

Video Hits |

1984–93 |

|

Rita and Friends (see Rita MacNeil) |

1994–97 |

|

CBC Arts: Exhibitionists |

2015–20 |

|

Comedy Programs |

|

|

The Wayne and Shuster Show (see Wayne and Shuster) |

1954–89 |

|

1976–84 |

|

|

Royal Canadian Air Farce |

1980–84, 1993–2007 |

|

1983– |

|

|

1987–92 |

|

|

1988–94 |

|

|

1992– |

|

|

The Red Green Show (see Steve Smith) * |

1997–2006 |

|

Kenny vs. Spenny * |

2003–04 |

|

The Rick Mercer Report (see Rick Mercer) |

2004–18 |

|

The Ron James Show |

2009–14 |

|

Baroness Von Sketch Show |

2016–21 |

|

Sitcoms |

|

|

King of Kensington (see Al Waxman) |

1975–80 |

|

Hangin’ In |

1981–87 |

|

The Newsroom (see Ken Finkleman) |

1996–97, 2003–05 |

|

Twitch City (see Don McKellar) |

1998, 2000 |

|

Made in Canada (see Rick Mercer) |

1998–2003 |

|

Les Bougon: C'est aussi ça la vie |

2004–06 |

|

2007–12 |

|

|

Mr. D (see Gerry Dee) |

2012–18 |

|

2015–20 |

|

|

2016–21 |

|

|

Workin’ Moms |

2017–23 |

|

Run the Burbs |

2022– |

|

Son of a Critch (see Mark Critch) |

2022– |

|

Game Shows |

|

|

1957–95 |

|

|

1961–85 |

|

|

Flashback |

1962–68 |

|

What on Earth |

1971–75 |

|

This Is the Law |

1971–81 |

|

Quiz Kids |

1978–82 |

|

Smart Ask! |

2001–04 |

|

Family Feud Canada |

2019– |

|

Reality TV Programs |

|

|

A Way Out |

1970–77 |

|

Celebrity Cooks |

1975–79 |

|

Wok with Yan |

1980–82 |

|

La Course destination monde |

1988–99 |

|

The Greatest Canadian |

2004 |

|

Dragon’s Den |

2006– |

|

Battle of the Blades |

2009–13, 2019– |

|

Canada’s Smartest Person |

2012–18 |

|

Qui êtes-vous? |

2013– |

|

The Great Canadian Baking Show |

2017– |

|

Talk Shows |

|

|

Tout le monde en parle |

2004– |

|

The Hour |

2005–10 |

|

George Stroumboulopoulos Tonight (see George Stroumboulopoulos) |

2010–14 |

|

Current Affairs Programs |

|

|

Tabloid |

1953–60 |

|

Viewpoint |

1957–76 |

|

Take Thirty |

1962–84 |

|

1964–66 |

|

|

1972– |

|

|

The Watson Report (see Patrick Watson) |

1975–81 |

|

1975– |

|

|

The Journal |

1982–92 |

|

Midday |

1985–2000 |

|

Venture |

1985–2007 |

|

Adrienne Clarkson Presents (see Adrienne Clarkson) |

1988–99 |

|

Undercurrents |

1994–2001 |

|

Mansbridge One on One (see Peter Mansbridge) |

1999–2017 |

|

Power & Politics |

2009– |

|

Rosemary Barton Live |

2020– |

|

Science and Documentary Programs |

|

|

1960– |

|

|

Telescope |

1963–73 |

|

Land and Sea |

1964– |

|

Klahanie |

1967–78 |

|

Witness |

1992–2004 |

|

The Passionate Eye |

1992– |

|

Absolutely Canadian |

1998–2009, 2012– |

|

Doc Zone |

2006–2016 |

|

Firsthand |

2015–17 |

|

CBC Docs POV |

2017– |

|

One-Hour Dramas |

|

|

Quentin Durgens, M.P. |

1965–69 |

|

Wojek |

1966–68 |

|

Seeing Things |

1981–87 |

|

Lance et Compte/He Shoots, He Scores |

1986–89 |

|

Street Legal |

1987–94 |

|

North of 60 |

1992–97 |

|

Da Vinci’s Inquest |

1998–2005 |

|

This is Wonderland |

2004–06 |

|

Intelligence |

2006–07 |

|

The Tudors |

2007–10 |

|

Being Erica |

2009–11 |

|

Republic of Doyle (see Allan Hawco) |

2010–14 |

|

Arctic Air |

2012–14 |

|

2013– |

|

|

The Porter |

2022 |

|

Miniseries |

|

|

Duplessis |

1977 |

|

1980 |

|

|

1985 |

|

|

Canadiana Programs |

|

|

Images of Canada |

1972–76 |

|

Canadian Reflections |

1978– |

|

On the Road Again |

1987–2007 |

|

Life and Times |

1996–2007 |

|

2000–01 |

|

|

Still Standing (see Jonny Harris) |

2015– |

* Also aired on/co-produced by another network.

Radio Programming

One of the most popular programs on CBC/Radio-Canada is the long-running arts and culture program q. It is broadcast to audiences around the world and is distributed in the United States by Public Radio International. The show, created in 2007, has become the most popular program ever in its morning time slot on CBC Radio. For many years, it had the largest audience of any current affairs program in Canada. That title has recently been claimed by Marketplace, the CBC’s flagship consumer affairs show.

Other programs of note include the news and current events coverage on As It Happens, the pop culture stories told by Definitely Not the Opera (1994–2016), the comedy skits of Wiretap and The Debaters, the nation-wide call-in show Cross County Checkup, the internationally acclaimed storytelling of the late Stuart McLean on The Vinyl Café, and the current affairs program The Current.

CBC/Radio-Canada operates ICI Musique as well as CBC Music, a free digital music service from which users can stream music online and access content from both CBC Radio 2 and Radio 3. The service aims to showcase Canadian talent alongside other international music and is a promoter of Canadian singers and songwriters. The first CBC Music Festival was held in 2013.

In addition to television and radio programming, CBC News is an important news organization, operating hourly radio news updates, TV news programs and an online news website. The broadcaster operates 14 foreign bureaus that contribute to its coverage of world events. The 24-hour television news network, CBC News Network (originally launched in 1989 as CBC Newsworld), is owned and operated by the CBC and is funded primarily by subscriber fees and other commercial revenue. Ratings show that it ranks above all other similar news channels in Canada.

Local programming is included in schedules across the country, including regional news on TV, radio, and online. CBC News online covers local, national, and international events, in addition to coverage of sports, science, and the arts. Much of the coverage is accompanied by television clips or podcast options. CBC Aboriginal reports online news updates from across Canada that are pertinent to First Nations affairs.

Loss of Regulatory Functions

CBC TV’s news channels are required by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to be carried in every home in Canada with cable or satellite television. However, the strength of the CBC/Radio-Canada’s cultural presence has continued to weaken since the 1980s. It could be argued that some of the corporation’s problems have been worsened by the fact that it no longer performs the regulatory role assigned to it by the 1936 Broadcasting Act.

In 1956, the Royal Commission on Broadcasting chaired by Robert Fowler recommended creating a separate regulatory agency. In 1958, the Conservative government of John Diefenbaker passed a new Broadcasting Act. The task of regulating the broadcasting system was taken away from the CBC/Radio-Canada and given to a separate Board of Broadcast Governors (BBG).

At the same time, the CBC/Radio-Canada's board of governors was replaced by a 15-person board of directors. The task of running the corporation was assigned to a president appointed by the federal government. The BBG was replaced by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) in 1968. But the principle of a separate regulatory agency remained intact.

Taking regulatory functions out of the CBC/Radio-Canada’s mandate was likely inevitable. In the end, it enabled the corporation to concentrate on its main task of providing Canadians with high-quality radio and television programming. But it also reduced the ability of the corporation to influence the broadcasting environment in which it must operate.

Having to obey market principles, the CBC/Radio-Canada was unable to prevent the introduction of rival networks devoted to foreign programming. It could do nothing to ensure that funds for Canadian programming were generated by the rapid expansion of cable systems carrying foreign signals. It could only stand by helplessly as scarce programming resources were siphoned off by pay television. Nor could it secure for itself second channels in English and French to increase its audience share. The best it could do was to introduce the English Newsworld in 1989 and French RDI in 1995.

Government Funding

The CBC/Radio-Canada has often been criticized for having a top-heavy bureaucracy. But studies have shown that it compares well in efficiency and productivity with other public and private broadcasters around the world. The report of the Caplan-Sauvageau Task Force on Broadcasting Policy (1986) was encouraging for supporters of public broadcasting. But neither the Mulroney nor the Chrétien governments acted on its recommendations. The corporation was the subject of more studies in 1995, including its president's report (shelved) and a report by the Commons Committee on Broadcasting. None of these clarified the often contradictory goals set for the corporation or to solve its persistent financial difficulties.

Budget cuts made during the Chrétien-Martin era in the mid-1990s resulted in 2,400 layoffs by the broadcaster. Hundreds of millions of dollars were cut from its annual budget. By 1999, federal spending on the CBC/Radio-Canada had decreased to $748 million.

A study commissioned by the CBC/Radio-Canada in 2011 found that Canada ranked 16th out of 18 Western countries in terms of taxpayer contributions to public broadcasting. At $34 per person, Canada’s per capita level of funding was 60 per cent below the average of $87, higher only than the United States and New Zealand. In Norway, the nation found to have the highest level of funding, the equivalent of $164 per capita was allocated to funding the public broadcaster.

By the end of the financial year ending in 2012, the corporation received roughly $1.1 billion in government funding, in addition to $689 million in revenue from advertising and other sources. The broadcaster’s expenses totalled $1.8 billion for that year. In February 2024, its annual budget remained $1.8 billion per year. About 70 per cent of this comes from the government. The remaining 29 per cent comes from commercial revenue, including advertising and subscription fees.

Opposition and Support

The CBC/Radio-Canada continues to unite and divide the country alike. Some regard the broadcaster as an unnecessary use of public dollars and a distortion of the broadcasting marketplace. Others welcome its role as often the only source of news and other information in the remote areas of Canada, as well as a major supporter of the arts.

A cut of 10 per cent to its $1.1 billion in funding from Stephen Harper's Conservative government in the spring of 2012 was met with both applause and condemnation from the Canadian public. The budget outlined a $115 million cut to broadcaster's budget to be implemented over three years.

In a 2012 debate on the importance of federal funding for a public broadcaster, some argued that the broadcaster is no longer relevant in a digital, new media marketplace with a wide array of choices for consumers. It was suggested that the CBC/Radio-Canada audience pay directly for the service, as opposed to the taxpayer-based model. However, many argue that the broadcaster plays a crucial role as a single-payer producer of Canadian content — in addition to its importance in remote areas of Canada — and is thus a valuable use of government funds. A 2011 study commissioned by CBC Radio found that for every dollar spent on the corporation, four dollars of economic benefit were created.

As noted above, the CBC/Radio-Canada has a relatively low per capita public expenditure. Despite this, much debate surrounds its federal funding. Some have debated whether a public broadcaster should even exist. Accusations of wasteful spending are often cited as a reason to stop funding.

A variety of organizations have been set up in recent decades to protest or support the continuing public funding of the CBC/Radio-Canada. Numerous petitions have been organized to “free” it (from alleged political interference) or to “save” it from budget cuts that many regard as ideological. On the other end of the spectrum, campaigns labelling the broadcaster a “money drain” or seeking to expose alleged misuse of funds also attract a large following.

This discourse will likely not end anytime soon. Rather, it will most likely help to fine-tune the significant role the corporation plays in Canada's social fabric. In the meantime, the CBC/Radio-Canada has stated its intention to further increase Canadian content and its reach to remote areas, while increasing digital and online platforms and adhering to budget restrictions.

See also Broadcasting, Radio and Television; Cultural Policy; Radio Drama; Television Drama; Television Programming; French-Language Television Drama.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom