For most Canadians, the holidays, and the long winter that follows, are all about spending time with family — and eating. For this occasion, we’ve put together articles that trace the histories of seven classic, and idiosyncratically Canadian comfort foods hailing from the prairies to Québec to Newfoundland. And we’re not only providing you with the history and cultural context of each dish, we’re also providing the recipes so you can make them at home. Enjoy!

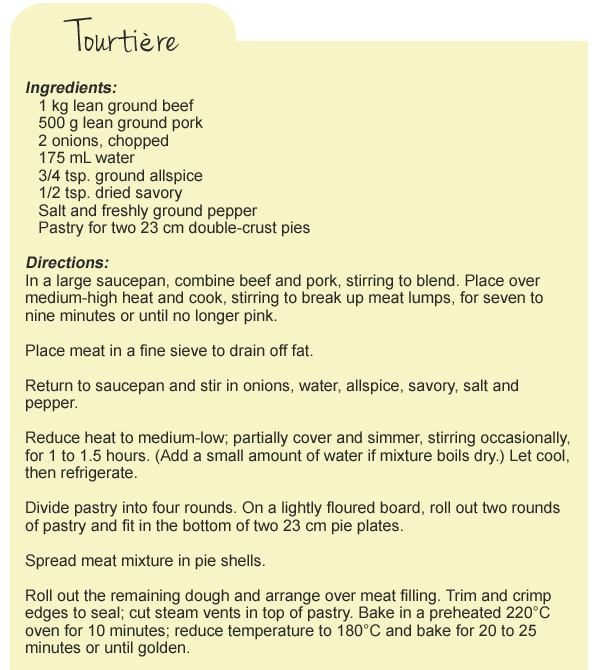

Tourtière

Tourtière is a double-crusted meat pie that is likely named for a shallow pie dish still used for cooking and serving tourtes (pies) in France. The ground or chopped filling usually includes pork, and is sometimes mixed with other meats, including local game, such as rabbit, pheasant or moose . It is famously served as part of réveillon, a traditional feast enjoyed by Catholic Québécois(es) after midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Tourtière can be a shallow pie that is filled with pork or other meats, or a many-layered pie that is filled with cubed meats and vegetables, which is the way the dish is prepared along the shores of the Saguenay and Lac Saint Jean. (Acadians living in the Maritimes call their version of tourtière by its common name, pâté à viande .)

Several recipes for tourtière were printed in La cuisinière canadienne (1840), likely the first French-language cookbook published in Canada. Pork, mutton, veal, potatoes (which came into use in the colony in the 1770s, by way of the British), and chicken all get their own treatment, simmered and spiced before they are enclosed in a sturdy pastry. Beef appears as the main ingredient in a recipe for Pâtésde Noël, which follows the tourtière recipe and its variations.

Poutine

While poutine is now available at fine restaurants and fast-food chains alike, it was completely unknown in the mid-20th century. The combination of fresh-cut fries, cheese curds and gravy first appeared in rural Québec snack bars in the late 1950s. Though the precise origins of poutine are much debated, in most cases, the dish was developed in stages.

Proximity to fromageries producing cheese curds in Centre-du-Québec was one key ingredient. Within the area, several towns and families lay claim to poutine’s creation. In Warwick (near Victoriaville, QC), Fernand Lachance of Café Ideal (later renamed Le Lutin qui rit) has said that he first added curds to fries at the request of Eddy Lainesse, a regular customer, in 1957. Lachance reportedly replied, “ça va te faire une maudite poutine!” (that will make a damned mess!), before serving up the concoction in a paper bag. The combination became popular, with diners customizing the dish by adding ketchup or vinegar. In 1963, Lachance began to serve the dish on a plate to contain the mess left on his tables. When customers complained that the fries grew cold too quickly on the plate, he doused the fries and curds with gravy to keep the food warm.

Fish and Brewis

Much of Newfoundland cuisine relies on salt. Fish and brewis (pronounced “bruise”), for example, was developed by fishermen who needed access to ingredients that could last through long fishing voyages, from weeks to months at a time. It is comprised of salt fish, salt pork, and hardtack, a type of hard, dry biscuit popular among sailors. Next to Jiggs dinner, fish and brewis is the quintessential outport (rural) Newfoundland dish.

“Brewis” refers to the preparation of the hardtack. Urban legends have it that “brewis” is a corruption of “bruised,” referring to the process of breaking up the hardtack into bite-sized chunks, but this is unsubstantiated; it is more likely a word of Middle English origin, meaning a broth made of bread, vegetables and meat.

The fish is salted cod, which was plentiful in Newfoundland until the 1992 cod-fishing moratorium. Cod was what spurred British colonization of Newfoundland after John Cabot arrived in 1497. The fishery was instrumental in the ascendancy of the British Empire, and was the economic cornerstone of Newfoundland until its collapse in the early 1990s. The fishery has since made only a modest recovery.

Canada is full of its own weird and wonderful snacks. From Pizza Pops to ketchup chips, this Secret Life of Canada episode dives into the history of Canadian food.Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

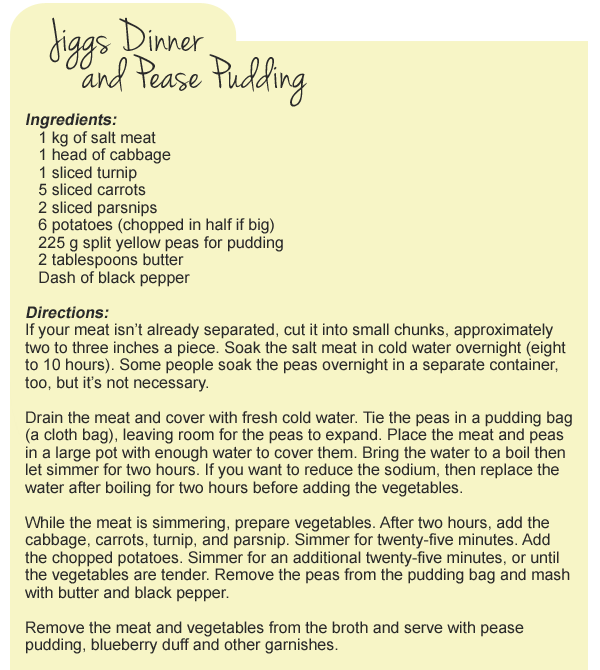

Jiggs' Dinner

Jiggs' dinner is a staple of outport (rural) Newfoundland cuisine. It is also called boiled, cooked or Sunday dinner, as it is usually served on Sunday. Most traditional recipes will be for servings for large groups of people, as large families and gatherings were the custom in pre-modernized Newfoundland.

A large portion of Jiggs was also meant to yield plenty of leftovers, which is commonly called “hash.” It is mixed together and fried in a pan with whatever can be found in the fridge. Hash with fried bologna on Mondays is very popular.

“Jiggs” is a reference to the protagonist of George McManus' comic strip Bringing Up Father. Jiggs was an Irish immigrant living in America who regularly ate corned beef and cabbage, a precursor to the Newfoundland dish. Much of the settlement in Newfoundland came from Irish immigration, so it is not surprising that so much of the food and culture has Celtic ancestry.

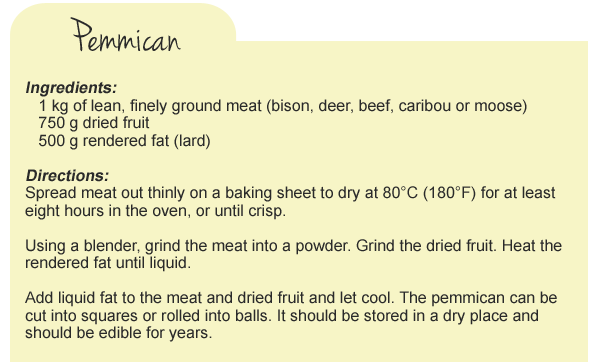

Pemmican

Pemmican (Cree pimikan, meaning "manufactured grease") is dried meat, traditionally bison (moose, caribou,venison or beef can be used as well), pounded into coarse powder and mixed with an equal amount of melted fat, and occasionally saskatoon berries, cranberries, and even (for special occasions) cherries, currants, chokeberries or blueberries. Cooled and sewn into bison-hide bags in 41 kg lots, pemmican was a dense, high-protein and high-energy food that could be stored and shipped with ease to provision voyageurs in the fur trade travelling in the prairie regions where, especially in winter, food could be scarce.

Peter Pond is credited with introducing this vital food to the trade in 1779, having obtained it from the Chipewyans in the Athabasca region. Later, posts along the Red, Assiniboine and North Saskatchewan Rivers were devoted to acquiring pemmican from Aboriginal peoples living in the region as well as the Métis. Métis travelled onto the prairie in Red River carts (carts constructed entirely of wood and lashed together with leather), killed and butchered bison , converted the meat into pemmican, and shipped it in bags to such fur trading posts as Fort Alexander, Cumberland House, Fort Garry, Norway House and Edmonton House. Pemmican was sufficiently important to the regional economy that, in 1814, Governor Miles Macdonell passed the disastrous but short-lived Pemmican Proclamation, which forbade the export of any food supplies, including pemmican, from the Red River Colony, nearly starting a war with the Métis.

Pouding Chômeur

The Québécois dessert called pouding chômeur — poor man’s pudding, or more literally, pudding of the unemployed — is delectably rich and incredibly simple. The dish consists of a dollop of batter baked in a pool of caramel. It is most similar to a saucy pineapple upside-down cake, minus the fruit.

Legend has it that the pouding was created by factory workers during the Great Depression, women making do with few ingredients, including butter, flour, milk and eggs. The sweet caramel sauce that bathes the simple batter was likely made from brown sugar during economic hard times, and was later replaced with maple syrup. The dessert is considered to be quintessential Québécois cuisine and The Oxford Companion to Food notes that it draws on French cooking techniques that were adapted to a new environment. Made with maple syrup, as opposed to brown sugar, the dish is an example of the province’s syncretic cuisine that, since colonization, has combined ingredients from Aboriginal traditions with European foods.

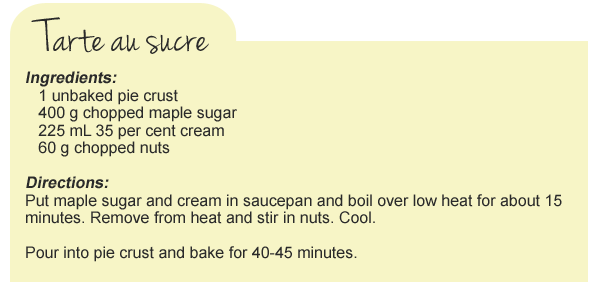

Tarte au sucre

For many early Canadiens, maple was the only form of sugar and was used ubiquitously in every dessert, the most basic of which is maple syrup drizzled on fresh snow. There are countless varieties of maple related desserts. Puddings, of British origin, were adapted to include maple sugar and the famous tarte au sucre is actually a common sweet in France and can be found in almost any patisserie. In Louisiana , the pecan pie is a variation of this tarte, and in Kentucky transparent pie is pecan pie without the pecans. Butter tarts in English Canada are another version of this, sweetened with brown sugar.

What distinguishes the French Canadian version of many of these desserts is the insistence of maple sugar or syrup as the sweetener. Brown sugar, in the earliest days, was a rare product and unavailable in Québec. It has gradually come to replace the maple flavor so tarte au sucre — originally made with maple syrup — now contains brown sugar. However, many desserts, such as tarte au sucre d’érable, have survived in their original form and are often the final chapter in a modern meal.

~

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom