Social conditions, including health, income, education, employment and community, contribute to the well-being of all people. Among the Indigenous population in Canada (i.e., First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples), social conditions have been impacted by the dispossession of cultural traditions, social inequities, prejudice and discrimination. Social conditions also vary greatly according to factors such as place of residence, income level, and family and cultural factors. While progress with respect to social conditions is being achieved, gaps between the social and economic conditions of Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people in Canada persist.

Funding for Social Services

Historically, the federal government has been responsible and provided funding for nearly all the social programs and services provided to Indigenous peoples in Canada. First Nations peoples registered with Indian status receive federal funds for social programs on reserves through the Indian Act. The funding is directed to First Nations band administrations. In the past, discriminatory sections in the Indian Act have prohibited some people, particularly women who married non-status men, from accessing social services. (See also Women and the Indian Act.) Inuit, Métis and non-status First Nations peoples receive funding through the department of Indigenous Services Canada, created in 2017.

National, provincial and territorial Indigenous representative organizations such as the Assembly of First Nations, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami often have mandates that include the improvement of social conditions and represent or advocate for the interests of their members. Many of these organizations receive funding from the federal government. Friendship Centres (non-governmental agencies) also provide various programs and services to urban Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous Populations in Canada

In 2016, 1,673,785 people reported an Indigenous identity, making up 4.9 per cent of the Canadian population. Additionally, 977,230 people reported being First Nations (including status and non-status people), 587,545 reported being Métis, and 65,025 reported being Inuit. Since 2006, the Indigenous population has grown by 42.5 per cent. This represents a growth rate four times that of the non-Indigenous population.

The Indigenous population of Canada continues to be predominately urban. According to the 2016 census, 867,415 Indigenous people lived in a city of more than 30,000 people, accounting for over half of the total Indigenous population. During this same period, metropolitan areas with the largest Indigenous populations were Winnipeg (92,810), Edmonton (76,205), Vancouver (61,460) and Toronto (46,315).

Income Levels and Education

In 2019, the rate of employment for Indigenous peoples in Canada (57.5 per cent) was lower than the non-Indigenous population (62.1 per cent). The rate for First Nations people (over 15 years old) was 53.8 per cent, 61.3 per cent for the Métis and 49.0 per cent for the Inuit. (See also Economic Conditions of Indigenous People).

In comparison to non-Indigenous peoples, Indigenous peoples’ income tends to be below the Canadian average. In 2016, the median after-tax income for non-Indigenous people was $31,144. For those who identified as First Nations, it was $21,253, for Métis, $29,068, and Inuit, $23,635.

In 2016, 68.3 per cent of the Indigenous population aged 25 to 64 had a post-secondary certificate, diploma or degree, compared to 70.4 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. Contemporary research has found that educational attainment rates and income are directly related. Indigenous educational programs are crucial to closing the income gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous wage earners. (See also Education of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Housing and Living Conditions

In 2016, one in five Indigenous people (19.4 per cent) lived in a dwelling that required major repairs, compared to 6 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. Mould, bug infestations, inadequate heating and contaminated water (see also Grassy Narrows) are just some of the issues that plague First Nations peoples living on reserves.

Overcrowding is another issue affecting Indigenous living conditions. In 2016, 18.3 per cent of Indigenous people lived in overcrowded housing, compared to 8.5 per cent of the non-Indigenous population. In the same year, 40.6 per cent of Inuit and 8.6 per cent of Métis lived in housing that was crowded. The number of First Nations people living in a crowded dwelling on reserve (36.8 per cent) was higher than First Nations people living elsewhere in Canada (18.5 per cent).

Health of Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous woman [on left is Doris Tait] bandaging the arm of another woman in the Community Health Workers Training Program, Coqualeetza, British Columbia.

The overall health of Indigenous people has improved in recent years; however, it continues to lag behind the overall population. For example, life expectancy can be 10-15 years shorter for Indigenous peoples and infant mortality rates can be two to four times higher. The tuberculosis rate for Inuit is over 290 times higher than non-Indigenous people.

Suicide rates among First Nations youth are around 5 to 6 times the national average, while Inuit youth rates are approximately 10 times the national average. The causes for high rates of suicide are multiple and may include depression due to social, cultural or generational dislocation; drug and substance abuse; or lack of housing, food and access to opportunity. (See also Suicide among Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

Increased urbanization of the Indigenous population has resulted in a greater incidence of diseases characteristic of modern society, such as cardiovascular disease, cancers and type-II diabetes. Rates of HIV/AIDS have increased. In 2016, there were 245 new HIV infections among Indigenous peoples, compared to 217 in 2014.

Proper access to health care is a concern in Indigenous communities. The case of Jordan River Anderson — a five-year-old Cree boy who died in hospital waiting for at-home treatment — demonstrates this point. (See also Jordan’s Principle.)

Food Insecurity

Indigenous households are more likely than non-Indigenous households to experience food insecurity. In 2019, 48 per cent of First Nations households did not have enough income to cover their food expenses. In comparison, the food insecurity rate for the country was 8.4 per cent.

People living in remote and northern communities have a more difficult time accessing and affording food. In Nunavut, for example, 46 per cent of households were affected by food insecurity in 2016. Access to certain foods such as fruit, vegetables and milk is more difficult because they must be transported long distances. The resulting high costs, limited availability and lower quality of the food contributes to food insecurity.

In some communities, the harvesting of traditional foods, such as seal, caribou, duck, whale and fish, helps to offset some of the issues accessing food. However, many communities continue to call on governments for increased support. (See also Country Food (Inuit Food) in Canada.)

Criminal Justice System

Indigenous people are over-represented in the criminal justice system as offenders and inmates, and under-represented as officials, officers, court workers or lawyers. Rates of incarceration among the Indigenous population continue to increase. In 2016-17, Indigenous adults accounted for 27 per cent of admissions to federal correctional services, compared to 23.2 per cent in 2013. Over-represented in federal corrections facilities, Indigenous peoples make up 20 per cent of the total imprisoned population even though they only comprise 4.9 per cent of the Canadian population. Indigenous youth are also overrepresented in the correctional system. They account for 46 per cent of admissions in 2016-17, while representing 8 per cent of the Canadian youth population.

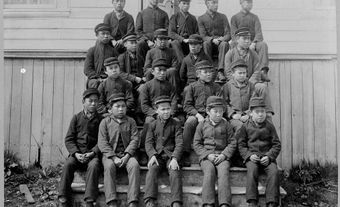

Several social factors have contributed to the over-representation of Indigenous people in the justice system. A history comprised of dislocation from traditional communities, disadvantage, discrimination, forced assimilation including the effects of the residential school system, poverty, issues of substance abuse and victimization, and loss of cultural and spiritual identity are all contributing factors. (See also PTSD: Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma.)

In a landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision, the Gladue case in 1999 advised that lower courts should consider an Indigenous offender’s background and make sentencing decisions accordingly, based on section 718.2 (e) of the Criminal Code. To date, many Indigenous-directed alternatives to incarceration in correctional facilities are being developed, including healing and sentencing circles. However, there are still many questions surrounding the unfair and inhumane treatment of Indigenous peoples in modern jails.

Because existing police forces are not always aware of the cultural differences and needs of Indigenous communities, Indigenous people began to develop their own police forces in the 1970s and 1980s. Indigenous police recruitment programs helped the RCMP and other police forces to add Indigenous constables to their staffs. In 1991, the federal government introduced the First Nations Policing Policy to meet the needs of Indigenous communities. While 62 per cent of officers in First Nations police services identified as Indigenous in 2018, Indigenous officers still only represent 4 per cent of police officers in Canada.

Indigenous Children and Families

In 2016, 60.1 per cent of Indigenous children under the age of four lived in a two-parent household and 34 per cent lived in a one-parent household. Comparatively, 86.2 per cent of non-Indigenous children lived in a two-parent household and 13 per cent lived with one parent.

Indigenous children are more likely to live in homes with grandparents. Among the Indigenous population in 2016, 21 per cent of First Nations, 11 per cent of Métis and 23 per cent of Inuit children under the age of four lived with at least one grandparent. Among the non-Indigenous population, 10 per cent of children aged four and under lived with at least one grandparent.

Since the 1960s, a large number of Indigenous children have been placed in care by social agencies. (See also Sixties Scoop.) In 2016, Indigenous children made up nearly half of all children in foster care in Canada, even though they only made up 7 per cent of children in the country.

Improving Social Conditions

Progress with respect to social conditions is being achieved. However, the gaps that persist between the social and economic conditions of Indigenous people in Canada and those of the general Canadian population continue to pose challenges. Areas of particular social concern include housing, employment, education, health, justice and family and cultural growth. Many communities are implementing community-based strategies stressing the importance of history and culture; governance, culture and spirituality; unique qualities and values; the link between self-government and economic development; and the role and importance of traditional economies.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom