Madawaska was a borderland that comprised parts of New Brunswick, Lower Canada, and the state of Maine, concentrated along the upper Saint John River valley. The region’s inhabitants, mostly Acadians and French Canadians, shared a similar language, religion, and cultural practices. In the 1840s, due to the growing timber industry, Madawaska became a source of conflict between the United States and British North America, each hoping to control the region’s rich forests. Although this borderland was eventually divided between the United States and Canada, locals preserved their cultural heritage, ignored imposed boundaries, and conducted business on both sides of the border.

What is Madawaska?

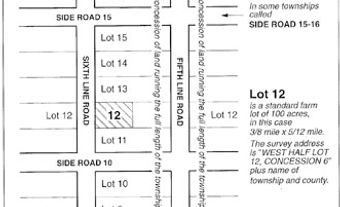

Defining Madawaska is a complicated endeavour, as it was neither an organized civil nor an administrative entity. There was no well-defined county, township, state, or colony that encompassed the entire region. It was a region that was defined instead by its people; they shared the same language, culture, and religion. Geographically speaking, however, Madawaska was a borderland that compromised parts of Québec, New Brunswick, and Maine, and was concentrated along the banks of the Saint John River. Specifically, it included the upper Saint John valley in New Brunswick, Témiscouata and southern Kamouraska in Québec, and Aroostook County in Maine. The name Madawaska comes from the Maliseet word meaning “land of porcupines.” It was the name of a river the flowed into the Saint John where the first residents of the valley (Aboriginal and European) settled.

Populating Madawaska

The first inhabitants of Madawaska were Aboriginal people, who settled on the banks of the Saint John, and fished and hunted the region’s rich wildlife. However, the people who eventually defined the region, and gave it its current distinct flavour, arrived in the years after the American Revolution.

Following the expulsion of 1755–64, several Acadians settled in the lower Saint John River valley (see The Deportation of the Acadians). The arrival of thousands of Loyalists in the region, however, forced many Acadians to consider another move. Not only were they worried that the Protestant and Anglophone Loyalists would increase pressures to assimilate, but they also feared that there would be very little land for their children and grandchildren. Moreover, since moving to areas with cheaper and more abundant land was very common for North American colonists, once their new homeland was overrun, it did not take much for some Acadians to move up river to Madawaska. Along with Acadians, French Canadians from the overpopulated Côte-du-Sud and Kamouraska regions also arrived in the area, looking for land.

Due to the successful timber industry, the population of Madawaska grew over the course of the 19th century. New Englanders and more French Canadians flocked to the region looking for cheap land and work in the timber camps. Very few Acadians migrated to the region during this time. Arriving from the Kennebec Valley, New Englanders lived in isolation of the French-speaking population, settling to the west, and focusing primarily on timber. French Canadians, on the other hand, sought to integrate with the original French-speaking population. Interestingly, however, there was a clear division between them and the original settlers. Most of these new immigrants had no family connection to the area, which caused some problems. Newcomers were viewed with great distrust, could not marry into these original families, and were even prohibited from making purchases on credit at the general store.

Daily Life

Though migrating from different regions, Madawaska’s inhabitants shared several commonalities. Most importantly, since the majority was Acadian and French Canadian, its population was therefore mostly French-speaking and Roman Catholic. Farming was also at the centre of life in Madawaska. Settlers not only farmed for subsistence, but also for trade, as they exchanged their goods at local stores for stuff they did not grow. Farmers in Madawaska grew wheat, barley, oats, potatoes, and even tobacco. They also raised cows and horses; the quality of their horses was well-known.

Although Madawaska was far from major North American trading centres, it was not isolated. It was along a significant route known as the Saint John-Grand Portage (Temiscouata Portage) route. As a result, Madawaskans imported and enjoyed many goods not indigenous to the area. They enjoyed all the exotic luxuries found in more settled areas like chocolate and spices, beer and whiskey, and tea and coffee. Madawaska families were quite large, as was the case with most French Canadian families, some having up to 14 children. Marriage was an economic necessity: a farm required both a husband and a wife to run smoothly.

Economy

Before the arrival of French-speaking settlers, the fur trade was the main economic activity in the region. Following their arrival, the area became known as a major wheat producer. So much wheat was being produced that settlers not only had enough for their own subsistence, but they also exported it. By the mid-1830s on, however, wheat production began to decline in the area, resulting from a series of bad harvests, longer winters, and western competition.

With wheat in decline, another industry took over: timber. Madawaska was home to vast pine forests that were so rich that it caused years of tension between the United States and British North America. Initially, settlers were only allowed to cut the trees on their land if they had received an official land grant from the government. Madawaskans would therefore sell the wood off their land to supplement their income from selling crops. Many families made good money by combining logging with agriculture. By the mid-1830s, however, the timber industry expanded as lumberers involved in large-scale clearing and milling flocked to the region. Several lumber camps opened in the valley attracting workers from all over the upper Saint John valley, Lower Canada, and New England.

A Disputed Territory

Madawaska was a disputed territory with three separate entities, at one point or another, laying claim to it: New Brunswick, Québec, and the United States. Starting in the late 1780s, both the Province of Québec and New Brunswick laid claim to the region, and for a short period, each asserting their authority over the region at the same time. Québec authorities not only claimed Madawaska as part of their territory in a 1790 map, but they even provided land grants to potential settlers. New Brunswick authorities similarly issued land grants. Obviously, this situation created several issues. Traders often contested each other’s trading licenses, leading to turf wars with numerous lawsuits between traders. In 1830, Britain finally put an end to this when it ceded all land west of the Madawaska River to Lower Canada (Québec), and the rest, and major part, to New Brunswick.

Things got a little more complicated with the arrival of American lumberers. The region’s vast and rich forests did not go unnoticed and in the 1810s, lumberers from southern Maine settled along the Saint John and the Aroostook rivers. This caused a land dispute, as whoever had jurisdiction over the region controlled the forests. One of these lumberers, John Baker, was at the forefront of a most peculiar moment. On 4 July 1827, Baker declared the independence of the “Madawaska Republic,” after which its inhabitants, he hoped, would ask to join the United States. Although most French-speakers ignored this declaration, the British Government in Fredericton charged him for sedition.

Though an isolated incident, there were tensions in the region. Since governments made money by issuing licenses or selling land to lumberers, both Maine and New Brunswick were unwilling to part with such a valuable commodity. To prevent further problems, London and Washington agreed to divide the disputed territory. That was not enough for Maine, however, who claimed the entire region. In 1831, they incorporated the area into a township. In 1839, the dispute almost led to war, the Aroostook War. Worried that “provincials” from New Brunswick were trespassing on Maine territory and illegally logging, the Governor of Maine, John Fairfield, sent Rufus McIntyre and an armed posse to stop all trespassers. However, they were captured by lumberers and sent to New Brunswick authorities, who accused them of invading the colony. New Brunswick authorities countered by stationing troops along the Saint John. Both sides also started to build blockhouses and military stations.

The dispute was finally resolved in 1842 with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. Accordingly, the disputed area was divided at the Saint John with the river acting as the boundary. Maine controlled the Aroostook valley and had free navigation rights on the Saint John. While Madawaskans living north of the river remained British, those living to the south became American citizens. The borderland was now a bordered land.

Ignoring Boundaries

Although on an administrative level the region now fell under American and British jurisdiction, at the local level, the situation remained relatively the same. French continued to be the language of communication on both sides of the river — and for several more generations and for some even today — despite pressures from the Maine government to Americanize their new French-speaking citizens. Several American families even continued to send their kids to school on the New Brunswick side. Both sides also continued to practice Catholicism. In fact, American Madawaskans continued to travel to St. Basile (in New Brunswick) for mass and until the 1860s remained under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Fredericton. When the new Diocese of Portland was created in 1859, which could have served the American side of the valley, the Bishops of Portland, Saint John, and the Archbishop of Halifax all agreed that the valley should not be divided. They argued that the people of the region were against this and that dividing them could compromise the French character of the region in Maine. In fact, it was the American Madawaskans themselves that eventually asked to be placed under the Diocese of Portland, arguing that crossing the river in the winter was too difficult, forcing several inhabitants to miss mass.

From a business perspective, the border also changed little. For example, as a consumer economy developed, consumers continued to travel between New Brunswick and Maine for commodities. John Emmerson, a storekeeper and middleman based in Edmundston, New Brunswick, continued to supply shop owners on the south side of the river with goods. For example, he supplied lumber camps on both sides of the border with provisions and material. This constant “smuggling” was a source of concern with one local merchant, John Costello, complaining that smugglers frequently crossed the river bringing liquor, tea, tobacco and other products into Maine. The forest industry also continued to blur boundary lines, as men from Maine, New England, New Brunswick, and Lower Canada continued to flock to the region to work in timber camps and lumber mills on either side of the Saint John. While Maine loggers often sent their wood to New Brunswick mills to be processed, others bought mills on the north side of the river, and vice versa.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom