Background

By the summer of 1866, the colonial legislatures of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada had agreed to proceed with Confederation. (Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland had participated in the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences. But they did not join Confederation until 1873 and 1949, respectively.) They now required the consent of the British Parliament. A draft for a British North America bill was completed in London in July. It awaited the arrival of delegates from the colonies to agree to its details. It could then be submitted to the Parliament in London.

The bill was already on uncertain ground. The British government of Prime Minister John Russell had favoured Confederation. However, he was defeated in the House of Commons. Russell’s successor, Edward Smith Stanley (Lord Derby) appointed Henry Herbert (Lord Carnarvon) as colonial secretary. He took over the Confederation file. Carnarvon supported the British North America bill, but the new Derby government was weak. A political crisis in Parliament could halt the legislation’s progress and give its critics the chance to reject it.

Delays and Opposition

Plans were made for the colonial delegates to meet in London at the end of July 1866. The representatives from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick arrived. The Province of Canada delegation, led by John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier, did not.

Macdonald blamed Fenian troubles in Canada for the delay. In truth, he had concerns about political technicalities. For one, the constitutions of the two provinces (Ontario and Quebec) into which the Province of Canada would be divided were not yet approved by the colonial legislature. Also, Charles Tupper reminded Macdonald that an election would be held in Nova Scotia — largely on the question of Confederation — before May 1867. And its outcome was uncertain. “We must obtain action during the present session of the Imperial Parliament, or all may be lost,” Tupper wrote.

The Maritime delegates were in a potentially embarrassing situation. They could do nothing of consequence in London without the Province of Canada delegates, and they couldn’t return home without achieving their goal. Meanwhile, a separate, anti-Confederation group of visitors led by Nova Scotian Joseph Howe was also in London. (See also: Confederation’s Opponents.) They tried to turn British politicians against Confederation. Sir Charles Stanley Monck, governor general of the Province of Canada, stressed to Macdonald the importance of bringing “the Union scheme” before the British Parliament without further delay.

Macdonald’s Leadership

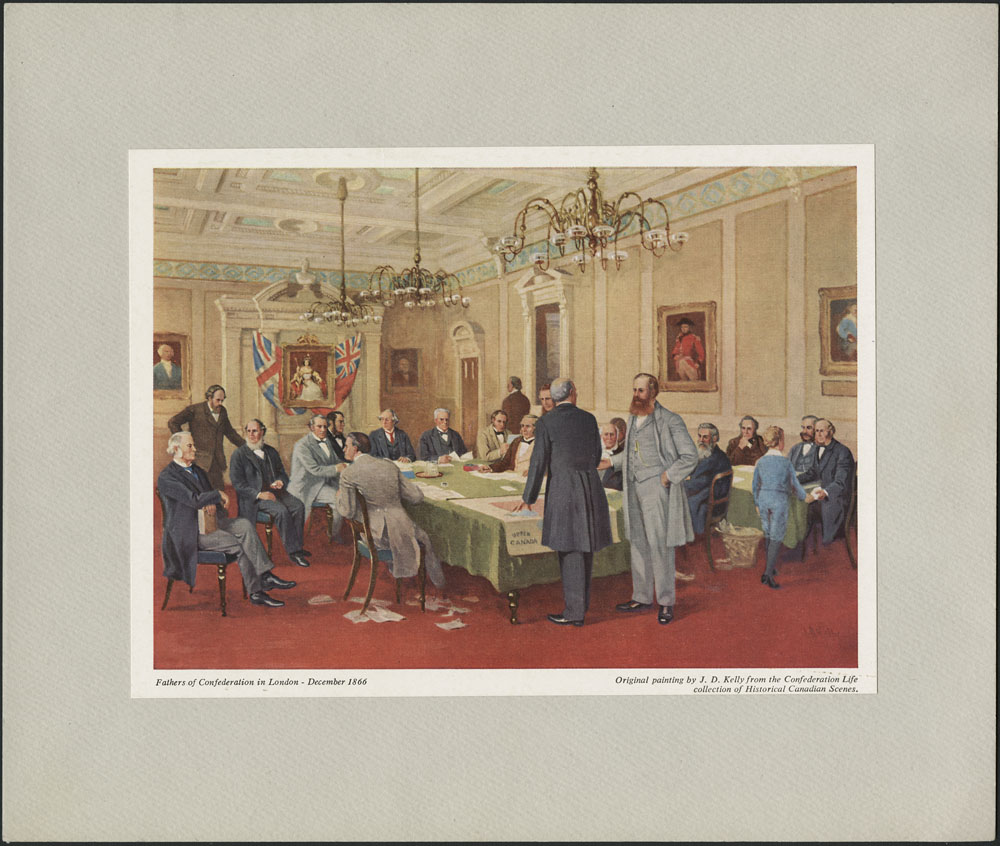

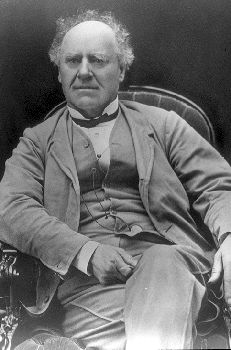

The Province of Canada delegation finally arrived in London in November 1866. The London Conference was held in a lecture hall in the Westminster Palace Hotel. The meetings began on 4 December and were chaired by Macdonald. His performance in the proceedings prompted Sir Frederic Rogers of the British Colonial Office to describe him as “the ruling genius” of the gathering.

Macdonald urged the delegates to agree that everything said and done in the meeting room be confidential. There would also be no recorded minutes. This left the dissenting Howe in the dark, as he was not a delegate to the conference. Macdonald also gained Carnarvon’s co-operation in avoiding any publicity that might “tend to premature discussion on imperfect information of the subject both in this country and America.”

Macdonald was well briefed on the political situation in Britain and the affairs of the Colonial Office. Howe attempted to discredit Macdonald as a drunkard. But Macdonald built a firm working and personal relationship with Carnarvon. Macdonald’s drinking habits — his “notorious vice” — did sometimes anger Carnarvon. But he still judged Macdonald to be “the ablest politician in Upper Canada.”

Debate of Quebec Resolutions

Macdonald now urged the delegates to work as quickly as possible. He wanted to avoid the risk that the election in Nova Scotia would result in an anti-Confederation government. (See also: Nova Scotia and Confederation; “The Anti-Confederation Song.”) He also needed to act while the Derby government was still in power in Britain. Since each change in the plan could lead to further demands, Macdonald wanted as few changes as possible to the already agreed upon Quebec Resolutions. They had been reached at the Quebec Conference in 1864.

The various delegates, however, believed it was their mandate to improve upon the 72 Resolutions. The most contentious had to do with educational clauses. For example, Roman Catholic bishops in the Maritimes, notably Archbishop Thomas Connolly of Halifax, sought guarantees for Roman Catholic separate schools. Alexander Galt wanted protection for the rights of the English minority in Quebec. And Samuel L. Tilley and Charles Tupper pressed for more federal subsidies for the Maritimes.

Delegates could not agree on just how binding the Resolutions should be. Some argued that improvements had to be secured before they could sign off on Confederation. Others disagreed. At a critical moment in the debate, Macdonald adroitly declared both sides right, but within definite limits. The delegates were thus able to thoroughly review all the Resolutions and make amendments. By late December, they had the newly named London Resolutions ready for submission to the Colonial Office, and later, to Parliament.

British North America Act

Macdonald wanted to call the new country the Kingdom of Canada. But the word “kingdom” was viewed with suspicion in the United States. The British did not want to provoke the Americans, so it was changed to “Dominion.” Tilley made this suggestion, inspired by a line from the Bible referring to God’s dominion (“He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth.”).

A final draft of the bill authorizing Canada’s confederation was presented to Queen Victoria on 11 February. It was read in the House of Lords the following day and passed through three readings in that house by the end of the month. It then passed through three readings in the House of Commons within two weeks. There was very little debate. The most notable event during this time was arguably the marriage of John A. Macdonald to his second wife, Agnes Bernard, on 16 February.

The British North America Act passed through the British House of Commons and House of Lords, and received Queen Victoria’s Royal Assent on 29 March 1867. The delegates then returned home. On 1 July 1867, the former colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada (now Ontario and Quebec) were officially proclaimed the Dominion of Canada.

See also: Constitution of Canada; Confederation: Timeline; Confederation: Collection; Fathers of Confederation; Fathers of Confederation: Table; Fathers of Confederation: Collection; Mothers of Confederation; Ontario and Confederation; Quebec and Confederation; Nova Scotia and Confederation; New Brunswick and Confederation; History Since Confederation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom