Sir Arthur William Currie (changed from Curry in 1897), soldier, educator (born 5 December 1875 in Adelaide (near Strathroy), ON; died 30 November 1933 in Montréal, QC). Currie was the first Canadian commander of the Canadian Corps during the First World War (his predecessors were two British generals, E.A.H. Alderson and Sir Julian Byng). One of the ablest generals of the First World War, Currie led the Canadian Corps to several important victories, particularly during the Hundred Days Campaign.

Brigade Commander

Currie began the war with no professional military experience but several years of service in the Canadian militia. One of his friends and junior officers in the 50th Regiment was Garnet Hughes, son of the minister of militia and defence, Samuel Hughes. Following the outbreak of the First World War, Garnet played a role in convincing his father to offer Currie a position in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and in September 1914, Currie became commander of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade.

However, before Currie accepted this position, he took over $10,000 from the 50th Regiment’s funds in order to pay off debts acquired through land speculation. This decision was made out of desperation, as Currie faced bankruptcy otherwise. But it would come back to haunt him.

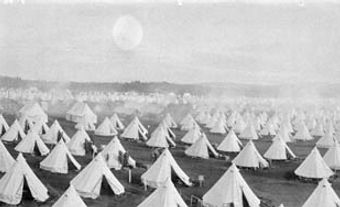

In October 1914, Currie crossed the Atlantic with the first Canadian contingent, arriving in England in the middle of the month. The Canadian troops spent the rainy winter living and training in Salisbury Plain, under the command of British general E.A.H. Alderson.

The Canadians crossed the English Channel to the European continent in February 1915. By April, they had transferred to the dreaded Ypres (Ieper) salient, where they participated in the Second Battle of Ypres (April–May 1915), which saw the first use of chlorine gas by the German army. Currie’s brigade lost about half of its strength during the battle.

Commander of the 1st Canadian Division

Following the addition of a second Canadian division, Alderson was promoted to command the newly created Canadian Corps and Currie became commander of the 1st Canadian Division (September 1915). (In May 1916, Sir Julian Byng replaced Alderson as commander of the Canadian Corps.) In June 1916, Currie’s division took part in a well-planned and successful counterattack against German forces at Mount Sorrel. In September, the Canadian Corps arrived at the Battle of the Somme; like the rest of the Corps, Currie’s 1st Canadian Division suffered heavy losses for little gain. However, the Canadians proved their mettle at the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 1917), a victory orchestrated by Byng and executed by Currie and the other officers and men of the Corps.

Commander of the Canadian Corps

When Byng was appointed to command one of the British armies, he recommended Currie as his replacement; Currie was knighted and became commander of the Canadian Corps on 9 June 1917, the first Canadian to hold that post. Not long after his appointment, he defied the wishes of Sir Sam Hughes (no longer a member of Cabinet), who wanted his son promoted to command of the 1st Division. Instead, Currie appointed Archibald Cameron Macdonell, making an enemy of the Hughes family.

It was around this time that rumours of embezzlement began to circulate about Currie. Fighting off bankruptcy, Currie had in 1914 diverted over $10,000 of the 50th Regiment's money to cover his personal debts. In 1917, the affair came to the attention of Prime Minister Borden, who refused to consider court-martialling Canada's best soldier. Currie borrowed money to repay the funds, but the rumour damaged his reputation among politicians at home. In contrast, he was well-respected on the battlefront as a military leader.

In August 1917, Currie and the Canadian Corps achieved a hard-won victory at Hill 70. In October, they moved north to join the Passchendaele campaign. Currie carefully planned a four-phase attack, which took place from 26 October to 10 November. The Canadian successes at Hill 70 and Passchendaele proved the worth of Currie and the Canadian Corps; however, at losses of almost 30,000 killed or wounded during the campaign, these victories had come at a heavy cost.

The heavy losses of the battlefront meant that recruitment was not keeping up with demand. This reality, combined with pressure by Prime Minister Borden and the Union coalition, led Currie to publicly support conscription in December 1917. Liberal politicians criticized Currie, accusing him of callous disregard for his soldiers’ lives.

Currie is best known for his planning and leadership during the Hundred Days Campaign (8 August–11 November 1918), the most successful of all Allied offensives, which led to the defeat of Germany and the end of the war. Under Currie’s leadership, Canadian soldiers won several important victories, including the battles of Amiens, Cambrai, Valenciennes and Mons. However, the Canadian Corps also lost 45,800 casualties during this period, contributing to rumours among the troops that Currie was a callous and cold-hearted leader who sacrificed Canadian soldiers for the sake of his own reputation.

Reputation and Controversy

Currie is widely considered one of the ablest generals of the First World War. Among his strengths were his emphasis on planning and preparation, and his recognition of artillery’s importance to trench warfare. Prime Minister Borden held Currie in high esteem, and British wartime Prime Minister David Lloyd George called him a “brilliant military commander.” There is even evidence to suggest that Lloyd George at one point had considered appointing Currie commander of all British forces.

However, Currie was heavily criticized for his decision in the final days of the war to commit Canadian soldiers to a number of costly (and what seemed to some, unnecessary) battles — particularly the battle of Mons, Belgium, on the eve of the armistice. Much of this criticism stemmed from the personal and political animosity between Currie and Sir Sam Hughes, who had been minister of militia and defence at the beginning of the war. On 4 March 1919, Hughes publicly criticized Currie in the House of Commons for “needlessly sacrificing the lives of Canadian soldiers.” This contributed to postwar controversy over his generalship.

On 23 August 1919, Currie was appointed inspector general of the militia forces in Canada. He left that position in May 1920 to become principal and vice-chancellor of McGill University, a position he held until his death. Without benefit of post-secondary education himself, he was extraordinarily successful as a university administrator at a time of particular importance in McGill's development.

Yet the accusations about Currie’s generalship clearly bothered him, even though he did not publicly respond for several years. This changed in 1927, when a small-town newspaper, the Evening Guide (Port Hope, ON), characterized him as a butcher for ordering the attack on Mons. Currie sued the paper for libel and the resulting court case in 1928 completely vindicated his actions during the war.

However, the controversy took its toll, and Currie suffered a stroke not long after the trial. After several years of ill health, he had another stroke in early November 1933 and died later that month at the age of 58.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom