The welfare state in Canada is a multi-billion dollar system of government programs — many introduced in the 1960s — that transfer money and services to Canadians to deal with an array of needs including but not limited to poverty, homelessness, unemployment, immigration, aging, illness, workplace injury, disability, and the needs of children, women, gay, lesbian, and transgender people. The major welfare state programs include Social Assistance, the Canada Child Tax Benefit, Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, Employment Insurance, the Canada and Quebec Pension Plan, Workers’ Compensation, public education, medicare, social housing and social services. Programs are funded and delivered by the federal, provincial and municipal governments.

What Is the Welfare State?

While the French term État‑providence has been used in Europe since the mid-19th century, its English counterpart, welfare state, appears to have entered the English language in 1941 in a book written by William Temple, Archbishop of York, England. For many years after, postwar British society was frequently characterized (often pejoratively) as a "welfare state," but by the 1960s the term commonly denoted an industrial capitalist society in which state power was "deliberately used (through politics and administration) in an effort to modify the play of market forces." For Asa Briggs, the author of this definition in an article appearing in The Welfare State (1967), there are three types of welfare state activities: provision of minimum income, provision for the reduction of economic insecurity resulting from such "contingencies" as sickness, old age and unemployment, and provision to all members of society of a range of social services. Under this definition, Canada became a welfare state after the passage of the social welfare reforms of the 1960s (see Social Security).

Richard Titmuss, one of the most influential writers on the welfare state, noted in Essays on the Welfare State (1959) that the social welfare system may be larger than the welfare state, a distinction of particular importance in Canada, where the social services component of the welfare state is less well-developed. In addition to occupational welfare, there are a range of social welfare services provided by parapublic, trade union, church, and non-profit institutions. These are often funded by a combination of state and private sources.

Political Ideas

Social Democracy

To some writers, the expansion of the welfare state is a central political focus of social democracy because of the contribution of welfare state policies and programs to the reduction of inequality, the expansion of freedom, the promotion of fellowship and democracy, and the expression of humanitarianism. In Canada, such a view of the welfare state appeared in the League for Social Reconstruction's Social Planning for Canada (1935) and in the reports of social reformers, such as Leonard Marsh's classic, Report on Social Security for Canada (1943), written for the wartime Advisory Committee on Reconstruction. Politically, this view has been expressed in the platforms of the New Democratic Party (NDP) and its predecessor, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, and practised most notably by the postwar CCF government in Saskatchewan and NDP governments in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario.

In the contemporary period, social democratic ideas on social welfare continue to find expression in the briefs produced by the Canadian Labour Congress, Canada's largest trade union federation, which since 1961 has been allied with the NDP; in the publications of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, a think tank which is closely allied to both; and in the work of the Broadbent Institute, one of Canada’s newest organizations, a retirement project of former New Democratic Party leader, Ed Broadbent. A popular form of these ideas can be found in the books of investigative journalist Linda McQuaig such as The Wealthy Banker's Wife (1993), and Billionaires' Ball: Gluttony and Hubris in an Age of Epic Inequality (2012), co-authored with Neil Brooks.

Liberalism

It is the modern liberal — and not the social democratic — conception of the role of the Canadian state in the provision of social welfare that has been dominant. In 20th-century liberalism, as practised in Canada and elsewhere, the responsibility for well-being rests with either the individual or the family, or both. Simultaneously, there is a clear acceptance that capitalist economies are not self-regulating but require significant levels of state intervention to achieve stability. In relation to Briggs' definition, there is an emphasis in liberalism on the first two of the three welfare state activities: minimum income and social insurance.

The necessity to develop an economically interventionist but more cautious and residual social welfare state has been the theme of a number of major reports by British writers J.M. Keynes and William Beveridge, and of the Canadian Report of the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations (1940), the postwar White Paper on Employment and Income (1945) and the more recent federal Working Paper on Social Security in Canada (1973). It is an approach expressed in Mackenzie King's Industry and Humanity (1918), Harry Cassidy's Social Security and Reconstruction in Canada (1943), and also in Tom Kent's Social Policy for Canada (1962), which presaged the period of high social reform from 1963 to 1968. In the contemporary period, these ideas continue to find expression in the work of the Institute for Research on Public Policy and its magazine, Policy Options.

Conservatism

The modern conservative conception of the welfare state is guided by the principles of 19th-century liberalism, i.e., less government equals more liberty, from which follows the defence of individual pursuit of self-interest and the unleashing of competitive forces operating through private markets. The reduction of inequality through taxation, often held to be a goal if not a result of the welfare state, is considered antithetical to the pursuit of freedom and to material progress. If it is the pursuit of self-interest which leads to an economically robust society then a reduction through taxation of the incentive to accumulate more income and wealth will inevitably lead to less growth and less economically healthy society.

Consequently, the modern welfare state is criticized from the conservative perspective. In particular, it is often argued that social expenditures have become too heavy a burden for the modern state and that state expenditures on social programs divert resources from private markets, thus hampering economic growth. According to the conservative conception, the welfare state has discouraged people from seeking work and has created a large, centralized, uncontrolled and unproductive bureaucracy. Proponents of this view argue that the welfare state must be cut down and streamlined, and that many of its welfare activities should be turned over to charity and to private corporations. In reference to Briggs' definition of the welfare state, conservatives support only the minimum income activities of the contemporary welfare state.

This view of the welfare state is currently supported in Canada by many members of the Conservative Party. The idea of the conservative welfare state had its clearest expression in Charlotte Whitton's The Dawn of Ampler Life (1943) commissioned by John Bracken, then Conservative Party leader, to criticize the social democratic views incorporated in Marsh's Report on Social Security for Canada; it also appeared in the west in the writings of former Alberta Premier Ernest Manning; and, in Québec, in the publications of the Semaines sociales du Canada. In the contemporary period, this view is prevalent in the books and briefs produced by business-oriented research and lobby organizations such as the Fraser Institute and the C.D. Howe Institute, and the Canadian Council of Chief Executives, a business lobby organization representing Canada's largest companies. Social Canada in the Millennium by economist Tom Courchene, published by the C.D. Howe Institute, is representative.

Marxism

The re-examination of contemporary capitalist societies begun in the 1960s has also produced a Marxist interpretation of the welfare state. In this view, in societies such as Canada which are dominated by private markets, it is the exploitation of labour that supports the ever-increasing growth of capital in the hands of private employers. In this context, a major role of the modern state is the provision of an appropriately trained, educated, housed and disciplined labour force available to employers when and where necessary. To accomplish this, the welfare state becomes involved in the regulation of women, children and the family through laws affecting marriage, divorce, contraception, separation, adoption, and child support since the family is the institution directly concerned with the preparation of present and future generations of workers and in provisions for employment, education, housing, and public and private health.

These ideas found expression in Canada in the past in the publications of the Communist Party of Canada. They continue to find expression in works by university-based authors and in the pages of magazines such as This Magazine and Canadian Dimension.

Canada's Welfare State

Social welfare in Canada has passed through roughly four phases of development that correspond to the country's economic, political and domestic development.

Early Period: 1840–1890

In the early phase of capitalist development, the state's response to poverty and disease was largely regulatory in nature. Social welfare, considered a local and private concern, consisted of the care of the mentally ill and of disabled and neglected children (see Child Welfare), and the jailing of lawbreakers.

After Confederation, the provision of social welfare continued to be irregular and piecemeal, depending in part on the philanthropic concerns of the upper class — in particular of those women who viewed charitable activities as an extension of their maternal roles and as an acceptable undertaking in society. The first extensive debate on child welfare was led by J.J. Kelso in Toronto in the 1880s leading to the founding of the Toronto Children’s Aid Society in 1891 and to the first comprehensive provincial child welfare legislation in 1893. It was the beginnings of the child-saving movement in Canada. A similar approach was taken up by other provinces.

Reform of this system was based on the notion that the family was the basis of economic security. The institutionalization of the family and the social reproduction of labour began with laws to enforce alimony, to regulate matrimonial property and marriage, and to limit divorce and contraception. This was expanded with limits on hours of work for women and children. Compulsory education and public health regulations were developed primarily in response to the spread of disease and fears of social unrest. Provincial governments began to support charitable institutions with regular grants. In Ontario, the first evidence of permanent support was in the form of the Charity Aid Act of 1874 which also called for the regulation of charities. In Québec the Catholic Church was at the centre of the organization of charitable social welfare. The government of Québec did not begin to provide supporting grants to private charities until after the First World War.

Transitional Phase: 1891–1940

Although the main concern of the Canadian state remained the promotion of profitable private economic development, the state also came to be associated with providing a supply of appropriately skilled labour through the regulation of capital and labour, the maintenance of the family, and the recruitment of more immigrants. This was largely achieved by the use of state mechanisms to maintain stability in the economy and the family, and also through the signing of treaties with Aboriginal people to further free up land for European settlement. During the same period, charity workers and organizations began to consolidate and to battle ideologically, generally unsuccessfully, for control of social welfare.

First World War

The appearance of laws compelling children to attend school and giving public authorities power to make decisions for "neglected" children was part of a growing number of state interventions to regulate social welfare.

The first industrial relations law, the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act, was passed in 1907, allowing the state to intervene in relations between labour and capital.

The first compulsory contributory social insurance law in Canada, the Workmen's Compensation Act, was passed in Ontario in 1914. During the First World War, two important forces speeded the development of an interventionist welfare state: demands for the support of injured soldiers and for the support of the families left behind. Both led to a Dominion scheme of pensions and rehabilitation and, in Manitoba, to the first mothers' allowances legislation in 1916.

Several provinces followed with mothers' allowance legislation of their own, but it was restricted to providing minimal support to deserted and widowed women. By war's end, after the incorporation of many thousands of women workers into the wartime labour force, they were encouraged to step aside to provide employment for male heads of households.

The postwar era also ushered in the first (and brief) federal scheme to encourage the construction of housing, but it lasted only from 1919 to 1924. Despite considerable debate during the 1920s about whether to establish permanent unemployment, relief and pension schemes, the only result was the passage of the 1927 old-age pension law, and this was in part the result of the efforts of J.S. Woodsworth and a small group of Independent Labour members of Parliament. Under the law, the federal government shared the cost of provincially administered and means-tested pensions for destitute persons over the age of 70. It was a modest beginning. The law explicitly excluded Aboriginal people.

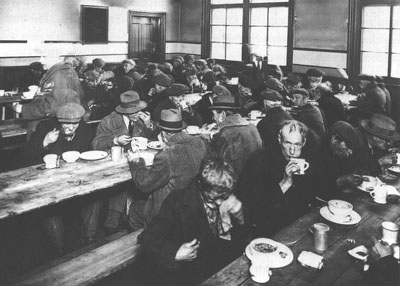

Great Depression

It was the trauma of the Great Depression that forced a change in social philosophy and state intervention. In 1930, with hundreds of thousands of Canadians unemployed, the newly elected Conservative government under R.B. Bennett legislated Dominion Unemployment Relief, which provided the provinces with grants to help provide relief. The government then opened unemployment relief camps run by the Department of National Defence, often in isolated locales, to give work at minimal wages to single unemployed men, and to keep them away from urban areas.

By 1935 the Conservative Party's stern resistance to social reform had been softened in the face of an economic catastrophe, with up to a quarter of the workforce believed to be unemployed. Continuing pressure from trade unions, and from relief camp workers and from social reformers for jobs, better wages and unemployment insurance, led Bennett to abandon reliance on the so-called natural "restorative" powers of capitalism in favour of social reform in Bennett's New Deal. This was introduced in a series of radio talks in January 1935. Later that same year, the Dominion Housing Act became the first permanent law for housing assistance. Bennett’s new interest in social welfare did not prevent electoral defeat in the fall of 1935. His government was replaced by a Liberal regime under William Lyon Mackenzie King.

Although the provinces objected on constitutional grounds to the New Deal's labour and social insurance reforms -- and the courts and the British Privy Council subsequently determined that the federal government did not have the power to pass such legislation -- the need for social reform was affirmed in the Report of the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations, created to examine the constitutional and social questions posed by the Depression. The Report recommended that the federal government take responsibility for employment and the employable unemployed, and the provinces for social services and for those people deemed to be unemployable, e.g., single mothers, pensioners and disabled persons.

The federal Unemployment Insurance Act was passed in 1940, after agreement with the provinces. A constitutional amendment to the British North America Act was necessary to give the federal government authority for unemployment insurance. The Tax Rental Agreements, arrived at with the provinces after protracted negotiations early in wartime, gave the federal government the right to collect income and corporate taxes for the duration of the war, a right it has retained to the present.

The Interventionist Phase: 1941–1974

Second World War

This phase marks the arrival of what is commonly called the welfare state. By the beginning of the Second World War, the economic and political lessons of the Depression had been well learned. Canadians increasingly accepted an expanded role of the state in economic and social life during the war, and expected this to continue after the war. To facilitate Canadian involvement in the war, Ottawa created a wide range of measures including the construction of housing, controls on rents, prices, wages and materials, the regulation of industrial relations, veterans pensions, land settlement, rehabilitation and education, day nurseries and the recruitment of women into the paid workforce in large numbers.

A wartime study in Britain by William Beveridge, released in December 1942, provided the promise of postwar employment and economic security. In the same month the federal government commissioned a report that offered similar promises for Canada — the Report on Social Security, prepared by Leonard Marsh and released in March 1943. The government largely ignored this and other wartime reports. Instead, Mackenzie King settled on a political compromise. At first this consisted of the creation of family allowances in 1944 — in order to undercut the wartime surge in electoral support for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, Canada’s social democratic party, founded during the Depression.

After re-election in 1945, the Mackenzie King government moved to dismantle much of the apparatus of state intervention constructed during the war. The White Paper on Employment, which appeared the same year, expressed the government's belief in the approach to economic management which followed from the work of the economist J.M. Keynes. The economy would be managed to produce full employment by providing assistance to private enterprise rather than by engaging directly in economic activity — or by providing further social welfare measures.

Still, at the Dominion-Provincial Conference that year, the King government presented the Green Book proposals, which included social assistance and hospital insurance measures, in order to gain concessions from the provinces on income and corporation taxes. The provinces did not agree, and the proposals were not subsequently revived until more than 10 years later.

Louis St. Laurent

Still, pressures for social reform continued. Under the postwar government of Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, public housing, federal hospital grants and assistance programs for disabled and blind persons were initiated. A trade union campaign for changes in pensions led to the creation of universal old-age pensions for those over 70, and means-tested old-age security for those between 65 and 70 in 1951–52. The new legislation required agreement from the provinces for a constitutional amendment. For the first time, cash benefits were extended to Aboriginal people.

An amendment to the Indian Act in 1951 extended the application of provincial social welfare legislation to Aboriginal people. One result was the disastrous program initiated in several of the provinces to take Aboriginal children into the care of the state, and to adopt many out to non-Aboriginal parents. In the 1960s these programs accelerated, leading to what became known as the “sixties scoop.”

The first permanent program for the funding of social assistance, the Unemployment Assistance Act, was put into place in 1956 after pressures from private charities and the provinces, which could no longer support the cost of relief at a time of increased unemployment.

John Diefenbaker

In 1957, the Liberal government was defeated in favour of the Progressive Conservatives under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. During this period, permanent programs for the funding of hospitalization, higher education and vocational rehabilitation were introduced or extended. The Diefenbaker government also introduced Canada’s first federal human rights legislation in 1960, and extended voting rights to Aboriginal people living on reserve.

The conflict in Saskatchewan as a result of the introduction by the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation government — of Canada’s first medical care insurance program in 1961 — led to a challenge to the program in 1962. The resulting “doctors’ strike” did not succeed, and medicare survived both this and the election of a new Liberal government in 1964. The popularity of medicare led Diefenbaker to appoint Saskatchewan judge Emmett Hall to head a Royal Commission on Health Services to investigate the possibility of a national medical insurance program. In 1964, Hall recommended a national program based on the Saskatchewan model. Diefenbaker also appointed Kenneth Carter to lead a Royal Commission on Taxation which recommended that all forms of income should be treated the same way for tax purposes (“a buck is a buck”).

Lester Pearson

The Liberal Party was returned as a reform-oriented government under Prime Minister Lester Pearson in 1963, on a cyclical economic upsurge. Influenced by the American "war on poverty," by the necessity to maintain the political support of the newly formed New Democratic Party (NDP), and by provincial reform initiatives, Pearson presided over the introduction of three major pieces of social legislation which constituted the last building blocks of the Canadian welfare state: The Canada (and Québec) Pension Plan, (1965) — which established a national compulsory contributory pension plan; the Canada Assistance Plan, (1966) — which consolidated the federal Unemployment Assistance Act, and assistance programs for persons who were physically disabled, together with provincial programs for single parents and people who were unemployed. It also made federal cost-sharing available for a range of social services including day care; and Medicare — which established a national system of personal health insurance administered by the provinces.

To these were added the Guaranteed Income Supplement, (1965) and the gradual reduction over the subsequent five years of the age of receipt of the universal pension to the age of 65. Also added were an increase in post-secondary education funding, and the consolidation of hospital, Medicare and post-secondary education funding in the Established Programs Financing Act, 1964, 1967 (see Intergovernmental Finance).

The National Housing Act was also amended in 1964 to provide loans on favourable terms to provincial housing corporations, clearing the way for more public housing. In the same year, the Indian ration system was transformed into a parallel system of Aboriginal social assistance, based on provincial legislation in each of the provinces. Only Ontario had an agreement, signed in 1965, to cover 100 per cent of on-reserve costs of social assistance and services. The point system was also introduced into the Immigration Act during the 1960s, paving the way for a substantial increase in immigration, particularly from Asia and the Caribbean.

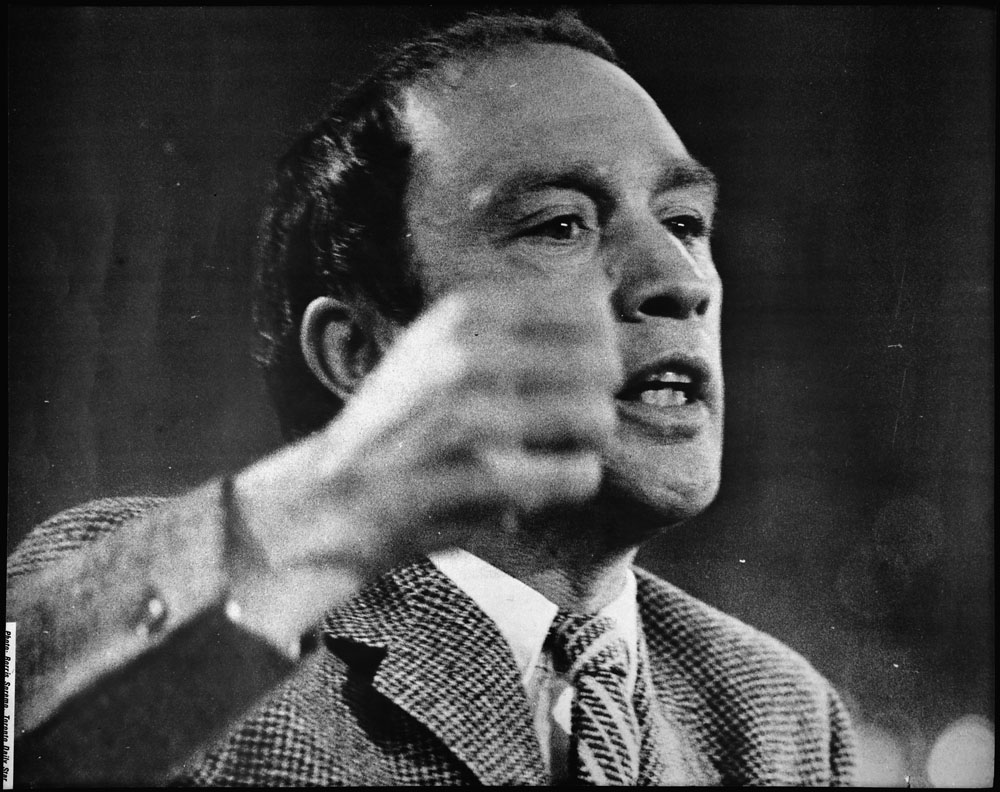

Pierre Trudeau

In 1969, the new Liberal government of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau brought in the ill-fated White Paper on Aboriginal issues which intended to abolish the Indian Act. It brought out a torrent of criticism which led to the withdrawal of the paper and the birth of the modern Aboriginal movement. In 1971, the government substantially expanded the coverage and benefits of Unemployment Insurance. Seasonal workers were included for the first time. With the support of the NDP, a Trudeau minority (1972–74) introduced some reorganization of Income Tax, the expansion of the National Housing Act to cover co-operative and non-profit assistance, and the first significant increase in Family Allowance since 1945.

The Social Security Review, launched in 1973, was intended to lead to joint federal-provincial expansion of public social services and assistance for the working poor. The Review was stalled by the lack of agreement between Ottawa and the provinces, especially Québec, and overtaken by economic decline. By this time, Québec, led by Premier Robert Bourassa, wanted greater autonomy in providing social programs. It was a prelude to the debates which would follow and which put social welfare policy at the heart of constitutional conflict.

The only further reform to appear was the child tax credit, in 1978 — an innovation that for the first time used the tax system to provide a social benefit, although the funds for it came from an equivalent reduction in the value of the Family Allowance.

Fourth Phase: Austerity and Constitutional Conflict 1975–2015

Expansion of Spending

In the 1970s, social spending began to increase as a result of the expansion of the range and number of social programs between 1964 and 1973. Increased funding made it possible to improve income security, particularly for the elderly as a result of the Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, for persons with disabilities, for single parents, and for the unemployed. Parents received a larger degree of income support for their children with additional funding for the federal Family Allowance.

Provincial social services, particularly child welfare and child care, improved in quantity and quality as a result of Canada Assistance Plan funding. Post-secondary education was expanded to cover a wider section of the population. And provincially administered health care became widely available for the first time as provinces began implementing medicare. In Québec, the Castonguay-Nepveu Report, 1971, led to the creation of a provincially run system of community health and social centres.

As unemployment grew, programs such as unemployment insurance and social assistance automatically expanded, pumping more income into the hands of people unable temporarily to provide for themselves. The impact of these latter increases on public spending was particularly evident from the mid-1970s, when the economy entered a period of decline after 10 years of growth.

Pressure on Spending

In the 1970s and early 1980s, rising inflation and the growing demands of newly unionized public sector employees increased demands on public expenditures as well. These conditions ushered in a new conservative political approach in which previous Keynesian beliefs were turned upside down. Decreasing government expenditures, particularly for social programs, was held to be the way to return to economic prosperity. The resultant unemployment was intended to reduce pressures for wage increases, to moderate inflation and to provide a stimulus to private economic development. Although inflation did moderate, relatively high unemployment meant continuing demands on social programs expenditures.

Agreement was reached in 1977 on the Established Programs Financing and Fiscal Arrangements Act between the provinces and the federal government, for a new set of formulas to distribute federal revenues — for health care, hospitalization and post-secondary education, and for equalization between the provinces. With amendment, this would remain the way Ottawa would share revenues with the provinces for the next 18 years.

Many of the methods begun in the early 1980s to control social spending have been used by governments since that time. These methods have include reducing eligibility and benefits, particularly under unemployment insurance and social assistance; "privatizing" provincial social programs by contracting out responsibility for services (particularly those relating to children and the aged); raising revenues through medicare premiums and user fees; decreasing social-program budgets relatively if not absolutely; taxing back assistance benefits; and terminating some social programs — for example, the federal Family Allowance in 1989.

The passage of the Canada Health Act in 1984 effectively ended the process by which physicians in some provinces had been opting out of medicare in order to charge higher fees.

Brian Mulroney

The election of a new Conservative government under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in 1984 brought in a repudiation of the postwar commitment to full employment, and to the role of government in the social well-being. The new government received or initiated several reviews of social policy: the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Economic Development, the Forget Commission on unemployment insurance, the Neilson Task Force Report on the Canada Assistance Plan, and a House of Commons Special Committee on Child Care.

Between 1984 and 1993, the federal government introduced a range of measures to reduce expenditures on social programs including gradually reducing old-age security benefits at middle income levels and above; eliminating family allowances; reducing the range of workers covered by and the benefits available under unemployment insurance; and limiting cost-sharing under the Canada Assistance Plan in three provinces in 1990.

Four other developments during the Mulroney years are worth noting for their implications for social policy. The signing of the Free Trade Agreement in 1988 and its passage later that year after an election fought over it, led into a substantial economic downturn especially in southern Ontario in the 1990s. With rising unemployment, the federal Conservatives were concerned that unemployed workers would soon be applying for cost-shared provincial social assistance. Fearing a rising funding commitment under the Canada Assistance Plan, Ottawa in 1990 placed a ceiling on the level of funding it would provide, forcing the province of Ontario to push its funding percentage to well beyond the 50/50 cost-sharing of the legislation. It was the beginning of the end of the Canada Assistance Plan.

Also in the same year, a violent confrontation between Aboriginal people and the police and military at Oka, Québec, led to a Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1991. The Commission's 1996 report recommended improvements in social services, health care, housing, education and social assistance.

In 1981-82 the Trudeau government had patriated the Canadian Constitution, with a new Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, Quebec had not ratified the changes. In 1987 the Mulroney government undertook new discussions with the provinces which resulted in the Meech Lake Accord. A key feature was the capacity of each province to opt out with compensation of any federal initiative in areas of provincial jurisdiction. This was aimed at federal social program funding, which successive Quebec governments had objected to since discussions on the Victoria Charter in 1971 failed over social policy. The provinces had three years to consider the Meech Lake Accord but not enough of them passed it to lead to ratification.

In 1992, another round of discussions led to the Charlottetown Accord, a further effort to create conditions that would convince Quebec to ratify the 1982 Constitution. Section III of the Accord set out conditions on federal spending in areas of provincial jurisdiction. It was also agreed to add a clause on Canada's Social and Economic Union, which included commitments to health care, social services and benefits, access to housing, food and other necessities, education, the protection of the rights of workers, and full employment. In October, 1992, the Accord was defeated in a pair of public referendums.

It is important to note the emergence of food banks, food programs, and the re-emergence of shelters for homeless people as a major part of the Canadian welfare state during the 1980s. The increase in the cost of housing in major cities, the growth of unemployment, the failure of both minimum wages and social assistance payments to keep up with the cost of housing, and the failure of governments to provide care facilities for people with persistent mental illness are among the continuing reasons for the growth in these charity-based institutions, and in homelessness, on the streets of Canadian cities.

Jean Chrétien

A new federal Liberal government under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien was elected in 1993. A discussion paper, Improving Social Security in Canada, was released in October 1994. It provided recommendations in four different areas: employment services, unemployment insurance, student loans and the Canada Assistance Plan.

The Chrétien government passed some program authority to the provinces. This would meet the demands of Québec in particular for greater social program autonomy, while also meeting the federal government’s agenda of greater austerity by reducing its social program commitments. Agreements with the provinces were negotiated to transfer responsibility for housing, and for employment support and training under unemployment insurance.

The 1995 budget announced the termination of the Canada Assistance Plan in 1996 and significant reductions in federal funding for social assistance, post-secondary education and health care. In 1996 the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) replaced the Canada Assistance Plan. Between 1994 and 1998 the government cut $6.3 billion in health and social program transfers under the CHST.

The termination of the Canada Assistance Plan opened the door for numerous changes to provincial social assistance programs. Influenced by developments in the United States, several provinces brought in their own versions of workfare, placing greater pressure on those who were deemed employable to find employment and leave welfare. In some instances people with addictions, and female single parents, were deemed to be employable and subject to workfare requirements.

The Chrétien government also made major changes in key federal social programs. The most significant reform of unemployment insurance since its expansion in 1971 took place in 1996 and 1997. Renamed Employment Insurance (EI), the revised program required 30 per cent more hours worked to qualify for new entrants and re-entrants, as well as other cuts and restrictions. The resulting EI surplus was eventually absorbed into the government’s effort to reduce the deficit and the debt.

Starting in 1996, the federal government conducted consultations about the reform of the Canada Pension Plan. From its inception in 1966, it was organized so that current contributions and accumulated surplus would provide the funds to pay out pensions. Ottawa decided to gradually increase the contribution rate to 9.9 per cent by 2003, at which point it would be stabilized at that level. The government also decided to create a crown corporation to hold and invest the funds collected but not needed to payout. The new organization was called the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB). Eventually all of the assets of the Canada Pension Plan (but not the Québec Plan) would be transferred to the new Investment Board.

In early 1997, federal-provincial discussions led to an agreement to create a new co-ordinated children’s benefit. The 1997 federal budget proposed the creation of a National Child Benefit system based on combining the Child Tax Benefit and the Working Income Supplement into one program. Federal-provincial discussions also proceeded on the development of a National Children’s Agenda and on a new program of income support for people with disabilities.

Also in 1997, the provinces and the federal government began further discussions on co-operation, which led in February 1999 to the Social Union Framework Agreement (SUFA) — signed by the federal government and all provinces except Québec. It was subject to review after three years. Section five — about spending for social programs — set out a spending arrangement in which Ottawa could initiate a direct (to individuals) program in the four areas of social benefits, social services, post-secondary education and health care with three months’ notice. New Canada-wide initiatives would require the agreement of a majority of provinces and changes to existing social programs would require consultation at least a year before renewal.

After the loss of substantial funds from health care, social assistance, social services and post-secondary education, successive federal-provincial agreements in 2000, 2003, and 2004 put funds back in. A year 2000 Agreement on Health Renewal and Early Childhood Development put in $18.9 billion, and $2.2 billion for early childhood development. A 2003 Accord on Health Care Renewal called for $34.8 billion for health care over five years. It also called for a new Canada Social Transfer (CST) and a Canada Health Transfer (CHT), a division of the block transfer into two parts effective 1 April 2004.

Paul Martin

Chrétien’s Minister of Finance was Paul Martin, responsible for implementing the federal reductions in social and health expenditures in the 1990s, and for negotiations that led to increased contributions to the Canada Pension Plan. Martin became prime minister in 2003. The following year he negotiated the 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care with the provinces, which would increase health funding by $41 billion. The purpose in part was to respond to the recommendations from the Report of the Royal Commission on the Future of Health Care (2002), led by Roy Romanow.

In November 2005 Martin reached the Kelowna Accord with the provinces, territories and Aboriginal organizations — an agreement to put $5.1 billion more funding primarily into Aboriginal education, health, and housing. But the Accord was rejected in 2006 by the new Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

Stephen Harper

Harper also cancelled a plan negotiated between the provinces by the Martin government on expanding child care spaces. Instead, the Conservatives passed the Universal Child Care Benefit which provided $100 a month per child to households caring for a child under the age of six — a program with a strong similarity to the Family Allowance cancelled by the Mulroney Conservatives on the grounds that it went to all households with a child regardless of income. The Harper Conservatives argued that the Universal Child Care Benefit would offer household choice of how to provide care for children.

The New Veterans Charter introduced in 2005 by the Martin government was passed into law in 2006. It was criticized by veterans’ organizations because it substituted lump sum payments for the long term, monthly support previously paid to disabled soldiers. A change in 2011 brought back some annual payments. As of 2015, the Charter still remained the subject of controversy.

The Harper government has focused much of its attention on the tax system, with three goals: reduce the size of government through reducing the growth of government revenue; put more money into the hands of citizens, especially those with higher incomes; and encourage more women to stay at home with their children.

The 2007 federal budget included an increase to age 71 of the time when holders of Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs) must begin taking funds out. In 2009, the Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) was introduced, allowing taxpayers to put savings and investments into a special account in which capital gains, dividends and interest are not taxable. By 2015, TFSAs could shield the gains from as much as $41,000 per account. Since its returns do not affect eligibility for the Old Age Security or the Guaranteed Income Supplement, the TFSA has been widely used by seniors as an alternative to a savings account. The 2009 budget also introduced an increased tax credit for children, an increase in the age credit and income splitting for seniors.

Harper's 2011 budget added additional benefits to the Guaranteed Income Supplement, and a $2,000 Family Caregiver tax credit. The 2012 budget increased the age of eligibility for the Old Age Security (and the Guaranteed Income Supplement) to age 67 starting with citizens who are 54 in 2012. Presented as a measure to assure the financial stability of the plan, there was little evidence to suggest these retirement programs were not sustainable. With evidence of the reduction of poverty among seniors due to these programs, critics expect that implementation starting in 2023 will lead to more seniors in poverty. For those who could afford to wait, the budget announced that the government would make it possible to defer the Old Age Security in return for higher benefits.

Erosion of Welfare State

Over the past 40 years successive federal and provincial governments have been focused on social expenditure control if not reduction. What has evolved is a return to the distinction between social programs for people with disabilities who are considered unemployable, and social programs for the non-disabled who are considered employable — and who should return to the labour market as soon as possible. Provincial and territorial social assistance programs have redefined single parents, mostly women, as employable, and subject to the same pressures to return to work. Only Québec introduced a major program to provide high quality child care at low cost. Child benefits which were increased substantially during the period have resulted in fewer children in poverty, especially those living in single parent households.

Since 1975, as a result of changes in social service programs and income support programs, social welfare has been eroded. One indication is the growing number of soup kitchens and food banks which have appeared since the 1980s across Canada. Another is in the growing numbers of the homeless. Without sufficient housing programs for people with psychiatric illness, and without sufficient social housing, the number of people living in shelters and on the street has been growing. A positive development has been the advent of Housing First programs in Toronto and elsewhere in the country, with the focus on helping homeless people into their own housing.

Social programs are still designed to deal with unemployment as a "contingency," an unusual occurrence, and not as the regular feature of economic and social life that it has become. This fact will no doubt continue to exert considerable pressure on future welfare state policy.

The aging of the population is also likely to become a major issue. As people live longer there will be a greater need for home care and for long-term care. Assisting Canadians to save more for their own retirement is another growing need. While the Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement have helped to keep many from poverty, there is a need to expand the Canada/Québec Pension Plan to provide greater replacement income in the future. Tax credits and deferred savings plans like the Registered Retirement Savings Plan have provided considerable benefit largely to higher-income households but such individual savings programs have not assisted the bulk of the population.

Resolving Aboriginal land claims, and improving education, drinking water, and housing in Aboriginal communities are the immense challenges to be faced by future governments, with Aboriginal leaders. Assisting the increasing numbers of Aboriginal people living off reserve is a further challenge.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom