Illustration, Art

The earliest printed image relating to Canada is a bird's-eye view of Hochelaga and environs, published by Giovanni Ramusio in Venice in 1556. This fanciful view owes more to the unknown artist's preconceptions about the nature of the country surrounding the future Montréal than to his immediate source, Jacques Cartier's written description of his visit to the Iroquois village in 1535.

Renderings of Explorers and Traders

Subsequent graphic renderings of the bare facts brought home by explorers and traders were to depend upon the interpretative facilities of engravers who had never visited the sights they depicted. This may likewise be said of the primitive sketches of Samuel de Champlain, published in his narratives of his voyages between 1604 and 1632; of Marc Lescarbot in his Histoire de la Nouvelle France (1609); of the botanist J.P. Cornut in his Canadensium Plantarum (1635-62); of Father François Du Creux in his Historia Canadensis (1660); and Father Louis Hennepin, in whose Nouveau voyage d'un pais plus grand que l'Europe (1698) is to be found the first recorded impression of Niagara Falls and perhaps the first true illustration of a Canadian landscape. In each case, firsthand experience was translated by second and third parties.

New France did not produce its own engraved imagery until after 1760, as it lacked both the market and the presses required for the printing of copper plates. The spread of British settlement in the Maritimes and in Upper Canada, however, included not only printers and publishers - and readers - but artists and engravers. The published views and charts of the topographers Thomas, Jefferys, Richard Short and Captain Hervey Smyth in the early 1760s, of J.W. Desbarres, author of The Atlantic Neptune, in the 1770s and 1780s, and of Joseph Bouchette in the 1830s, are testament to the interest that had been sparked in England by the establishment of a British presence in North America. These delineations of Halifax, Québec and other sites and sights may be described as "illustrations" only insofar as they were issued in multiple, reprographic formats, usually as bound or loose portfolios, with minimal letterpress.

The Military Artists

After conquest and colonization came exploration and exploitation. Almost from the beginning, probers of Canada's far-western, far-northern Pacific coast, and High Arctic regions felt duty-bound to back up their reports with their own or with colleagues' sketches and watercolours. This tradition, inculcated in the naval and military colleges as a discipline to sharpen perception and assist in the positioning of ordinance, extended roughly from the 1770s to the 1870s.

It embraces the published journals and voyages of the likes of James Cook (whose shipboard artist was John Webber), John Meares, Samuel Hearne, George Vancouver, Sir John Ross (whose 1819 Voyage of Discovery ... in His Majesty's Ships Isabella and Alexander features an aquatint after a drawing by a Greenland Inuit stowaway, John Sackhouse or Saccheuse), Edward Parry, G.F. Lyon, Robert Huish and F.W. Beechey.

Undoubtedly the most accomplished of the author-artists associated with boreal latitudes was George Back, whose on-site watercolours were first reproduced along with those of the equally gifted Robert Hood in Sir John Franklin's 1823 and 1828 narratives of northern expeditions. Back's own sketches, engraved by Edward Finden, grace his Narrative of the Arctic Land Expedition to the North of the Great Fish River ... (1836), but the stresses of his last, near-disastrous voyage, related in his Narrative of an Expedition in HMS Terror ... in the Years 1836-37), forced him to turn over the draftsman's role to his first lieutenant, William Smyth.

The disappearance of Sir John Franklin's 1845 expedition led to a renewal of public fascination with the polar and subpolar regions, as documented by numerous illustrated narratives. By the turn of the century, however, and the attainment of the North Pole and the traversing of the Northwest Passage, the attention of readers and publishers had turned to the Antarctic; the Arctic archipelago and islands would not be reclaimed for Canada until the expeditions undertaken for artistic purposes by members of the Group of Seven in the 1920s and 1930s.

By the 1770s, a new genre had entered the picture in the form of the illustrated land-travel narrative and its fictional and poetical counterparts (see Exploration and Travel Literature). A vast literature was an outcome of the arrival in the New World of entrepreneurs, settlers, tourists, naturalists, surveyors and fur traders with a penchant for diarizing and description. This printed material, as often as not, was complemented by engraved and lithographed interpretations of the scenery, buildings and peoples encountered during the course of journeys along waterways and the westward-advancing trails, roads and rails.

Perhaps the most pleasing such volume, from an artistic as well as literary point of view, is Travels Through the Canadas (1807), by a talented amateur exponent of the prevailing Picturesque style, George Heriot.

The year 1842 saw the appearance in London of 2 especially accomplished and influential publications: Coke Smyth's Sketches in the Canadas, and N.P. Willis's Canadian Scenery from Drawings by W.H. Bartlett, the former illustrated by lithographs, the latter by engravings. By mid-century, however, British interest had begun to wane, and North American publishers took over the issuing of travel and immigrants' guides, narratives and collections of views for European and - increasingly - domestic readerships.

The Introduction of Printing

The introduction of printing into Nova Scotia and Québec in the 1760s and 1770s, and Upper Canada in the 1790s, did not initially accommodate visual artists. What is considered to be Canada's first printed picture - a view of Halifax - appeared in the Nova Scotia Calendar in 1776.

Possibly the first engraved landscapes to be executed in Canada appeared in 1792 in John Neilson's Quebec Gazette: a view of Québec and another of Montmorency Falls, by J. Painter and J.G. Hochstetter respectively. The first known engraved portrait, also by Hochstetter, was printed in the Quebec Magazine in the same year. The capital of Lower Canada remained the hub of the graphic arts and printing industries until the ascendancy of Montréal in 1850s, and of Toronto in the 1870s and 1880s.

The Picture of Quebec, authored and illustrated by George Bourne, was published by David Smillie & Sons in Québec in 1829; Adolphus Bourne brought out views of Québec by R.A. Sproule in 1830 and, most significantly, Thomas Cary and Sons issued Quebec and its Environs by the military topographer James P. Cockburn in 1831. Bosworth Newton's Hochelaga Depicta (1839), featuring lithographs after paintings by James D. Duncan, was published in Montréal, while The British American Cultivator (1842), with wood-engravings by Frederick C. Lowe, was published in Toronto.

Up to this time, improvements in the standards of published illustrations were thwarted by the lack of trained engravers and lithographers to translate drawings or paintings into reproducible form. Work usually had to be sent to Europe or the US until skilled practitioners could be lured to Canada from abroad. Lithography, though invented in 1776, was not introduced into Upper Canada until Samuel Tazewell briefly established his lithographic press in Kingston in 1830.

It remained for Toronto's Hugh Scobie to make a success of the new technology, however, and the possibilities of this economical if cumbersome mode of reprography did not begin to be explored fully until tintstone lithography and its successor, chromolithography, and their abettor, the steam-driven rotary press, came to the fore in mid-century. As late as 1859, Paul Kane, author of perhaps the single-most important Canadian illustrated book of the 19th century, Wanderings of an Artist, had to resort to a London publisher to ensure that his paintings and watercolours were properly translated into chromolithographs and wood-engravings.

Agnes Dunbar Chamberlin had to make do with hand-colouring the black and white lithographs taken from her own watercolours to illustrate Catherine Parr Traill's Canadian Wild Flowers (1868), which did not appear in chromolithographic form until 1885.

The most common use to which lithography was initially put was the illustrated county atlas; later, it was adapted to the creation of advertising posters, billboards, trade cards and labels. A specialist in all these forms was the Toronto Lithographing Co, able to boast in the 1890s of being one of North America's largest and most advanced such firms. Its art department employed a number of the period's best-known artist-illustrators, among them W.D. Blatchly, William Bengough, J.D. Kelly, C.W. Jefferys and J.E.H. Macdonald. In 1909 the company was absorbed by Stone Ltd, which in turn joined Rolph and Clark to become Rolph, Clark, Stone in 1917. Hamilton, Montréal and Ottawa also supported major lithography houses.

Wood-Engraving

Wood-engraving came to Toronto in 1849 with the arrival of John Allanson, a Newcastle native who had trained under the master of the white-line block, William Bewick. Allanson's Anglo-American Magazine and Canadian Journal, both launched in 1852, were illustrated with views of Hamilton, Kingston and Toronto. Quality remained variable, however, until the immigration from London to Toronto of Frederick Brigden Sr. Buying out his partners, the Beale brothers, he renamed the company first the Toronto Engraving Co and then Brigden's Ltd. Catalogue, newspaper and trade periodical work became its forte.

Adapting to the new photomechanical processes that came along in the 1880s, the company flourished under the directorship of his artist son, F.H. Brigden. Brigden's opened a Winnipeg branch which, like its Toronto counterpart, attracted many well-known illustrators who also made reputations as painters and printmakers - among them Charles Comfort, H.E. Bergman, and Fritz Brandtner.

The scarcity of expert engravers in Montréal, and the growing numbers of skilled photographers, may have induced engraver William A. Leggo to formulate the world's first halftone reprographic process, Leggotype, in 1869. That year, the world's first magazine halftone appeared in the first issue of Canadian Illustrated News, published by G.E. Desbarats. The magazine survived until 1883 and was illustrated with Leggotypes up to 1871, when technical problems caused Desbarats to return to line-engravings as his mainstay.

Among prominent illustrators in his employ were William Cruikshank and F.M. Bell-Smith, who covered the Toronto scene, and Henri Julien, the weekly's Montréal artist. Though its population base and advertising clientele were not large enough to sustain so ambitious an undertaking, the paper inspired imitators, including Desbarats' own L'Opinion Publique (which shared visual content with CIN but was editorially independent) and Dominion Illustrated News, Canadian Graphic, and Saturday Night, which celebrated its 100th anniversary of continuous publication in 1987.

Grip was a journal devoted to politics produced by J.W. Bengough. He was author of A Caricature History of Canadian Politics (Toronto, 1886) and set up the Grip Printing and Publishing Co, which in collaboration with the Toronto Litho Co issued Canadian War News covering the 1885 North-West Rebellion. Grip Ltd, the graphic design company that grew out of the publishing concern, went on to employ Tom Thomson and most of the future Group of Seven - all trained as photoengravers, lithographers or illustrators.

The departure of their art director, A.H. Robson, in 1912, induced them to follow him to the rival firm of Rous and Mann Ltd or to seek careers as full-time painters of the Canadian wilderness. Group members Franklin Carmichael and A.J. Casson were subsequently lured to the leading Toronto silkscreening establishment, Sampson-Matthews.

The most ambitious Canadian publishing venture involving wood-engraving was Picturesque Canada. With text by George Monro Grant, it appeared in serial form in 1882-84 under the imprint of the Art Publishing Co, and in 2-volume book form in 1884. The publishers, H.R. and R.B. Belden, were American expatriates who had started out in Canada as producers of illustrated county atlases.

The art director, L.R. O'Brien, began to choose his subjects and commission artists and engravers as early as 1880. He encountered controversy almost immediately; however, his contention that the paucity of skilled Canadians meant that outsiders had to be given the task of depicting his country roused the fury of his chief rival, John A. Fraser, and precipitated Fraser's decamping for the US in 1882.

The Canadian contributors were O'Brien himself, Henry Sandham, Fraser, O.R. Jacobi, the marquess of Lorne, William Raphael, F.M. Bell-Smith and Robert Harris; the American contingent, headed by Frederick B. Schell and J. Hogan, vastly outnumbered its Canadian counterpart.

Setbacks in the 1870s and 1880s

The disappointment associated with Picturesque Canada and the economic depressions of the 1870s and 1890s drove more and more Canadians southward, led by Fraser and Sandham, who both enjoyed a measure of success as book and periodical illustrators in the last decades of the so-called "golden age of black-and-white." Their breakthrough into the American market attracted swelling numbers to follow in search of well-paying magazine, newspaper and book illustration jobs.

The wave, which had been anticipated by cartoonist Palmer Cox (inventor of "The Brownies"), portraitist Wyatt Eaton, and animal artist and writer Ernest Thompson Seton included J.A. Fraser's brother, W.L. Fraser, who edited Century Magazine; Jay Hambidge, later a prominent art theoretician, Charles Broughton and William Bengough, whose departure from Toronto in 1892 inspired coevals C.W. Jefferys, David F. Thomson and Duncan McKellar to follow.

Although the call of home and the displacement of the illustrator's role by that of the photographer made many return to Canada, a select few stayed to garner the rewards still to be won: Arthur Crisp, Arthur William Brown, Harold Foster, Robert Fawcett and Norman M. Price, the latter a book and magazine illustrator who had first made a name for himself in London as a founding member of Carlton Studios. This innovative advertising and publishing graphics house, founded 1902, was the brainchild of 4 former employees of Grip Ltd and members of the Toronto Art Students' League - Price, A.A. Martin, Arthur Goode and T.G. Greene - and employed J.E.H. MacDonald in 1904-07. Thomas Mower Martin, painted the watercolour landscapes for the most lavish successor to Picturesque Canada, Wilfred Campbell's Canada (1907), the front cover of which bears the Carlton Studios logo.

The Toronto Art Students' League (established 1886) fostered the cause of Canadian illustration and Canadian nationalism alike through the annual souvenir calendars it published between 1893 and 1904. Active contributors of decorative borders, lettering and drawings, which after 1895 were on explicitly Canadian themes, were C.W. Jefferys, C.M. Manly, Robert Holmes, F.H. Brigden, A.H. Howard, D.F. Thomson, J.D. Kelly, T.G. Greene, A.A. Martin, Norman Price and J.E.H. MacDonald. Especially brilliant are the art-nouveau cover designs of the otherwise obscure R.W. Crouch.

Intended to show off not only the skills of its contributors to potential clients and critics but the level of reproductive quality achieved by their printers, the calendars are proof that the supplanting of hand-engraving by photoengraving was not such a disaster as some opponents of the new medium had predicted. While betraying the influence of the leading American and European illustrators and designers of the day, they strike a distinctly native note in both style and content.

Though the league disbanded in 1904, to be replaced by the Maulstick Club, the Graphic Arts Club (later the Canadian Society of Graphic Arts) and the Arts and Letters Club, its legacy survived not only in the work of its most prolific and high-profile member, Jefferys, but in the paintings, illustrations and teaching activities of Manly, Holmes, Brigden and MacDonald, spiritual leader of the Group of Seven.

Jefferys went on to become Canada's most versatile all-round illustrator, adept at editorial and book as well as at newspaper and advertising work. Uncle Jim's Canadian Nursery Rhymes (1908), with text by David Boyle and drawings by Jefferys, may well be Canada's first colour illustrated children's book, but owing to the bankruptcy of its British printer it was never distributed in the country of its origin.

Similarly, his crowning illustrative achievements were the pen-and-inks he prepared for a projected but abortive edition of the works of Thomas Chandler Haliburton in 1915 (although it was published in 1956, after his death, under the title Sam Slick in Pictures). His only serious competitors as historical artists were his contemporary, J.D. Kelly, best known for his series of paintings for Confederation Life, and Kelly's successor, Rex Woods, probably the most technically accomplished practitioner in the field. His Québec equivalents were Henri Julien (as a master of pen-and-ink) and E.J. Massicotte, who after 1918 produced hundreds of drawings, paintings and engravings depicting French Canadian habitant life and customs.

These subjects were the stock-in-trade of F.S. Coburn, remembered as an illustrator for his interpretations in oils and pen-and-ink of the dialect poetry of W.H. Drummond, published in New York by G.P. Putnam's Sons. More ethnically authentic are the images provided by Symbolist painter Ozias Leduc to Dr E. Choquette's Claude Paysan (1869) and to Benjamin Sulte's Contes canadiens (1899); J.C. Franchère's decorations for his own Chansons canadiennes (1907); and M.A. Suzor-Coté for the most frequently illustrated piece of Québec fiction, Louis Hémon's Maria Chapdelaine (1916).

The exquisite tempera paintings executed by Clarence Gagnon for a deluxe Paris edition of this novel probably constitute the finest suite of book illustrations to be produced in this country, though Gagnon's pictures for L.F. Rouquette's Le Grand Silence Blanc (1929) come a close second.

Illustration and Design in the Early 20th Century

Nor were "legitimate" English Canadian artists reluctant to try their hands at illustration and design in the first third of this century, encouraged as they were by the enlightened editorial and art-directional policies of such supportive publishers as McClelland & Stewart, Ryerson Press (headed by Dr Lorne Pierce), Ottawa's Graphic Press, Macmillan (Canada), J.M. Dent (Canada) Ltd, Musson, and Rous and Mann Press Ltd.

Group of Seven members J.E.H. MacDonald, F.H. Varley, A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, F.H. Johnston, Frank Carmichael and Edwin Holgate all made significant contributions to the modernizing of the illustrated book in the 1920s and 1930s, as did their contemporaries Stanley Turner, W.J. Phillips, Bertram Brooker, J.W.G. Macdonald, Robert Pilot, Charles Comfort and A.C. Leighton.

Thoreau MacDonald, J.E.H.'s son, through his highly characteristic black and white work for Canadian Forum, Ryerson Press and his own private Woodchuck Press, deserves the title of Canada's most adept and well-loved book designer and illustrator. His production spans 6 decades, from the 1920s to the 1970s and, though much imitated, has never been equalled.

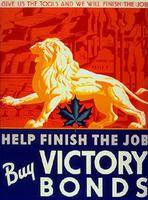

During both great wars, Canada's graphic artists, like its painters and sculptors, were called upon to support the national effort by contributing to the propaganda campaigns organized both by the federal government and by private industry (War Artists). The most noticeable form their endeavours took was the poster, WWI's most gifted exponent of which was Arthur Keillor. WWII's Harry Mayerovitch was a protegé of John Grierson of the National Film Board.

Post-World War II Illustration

After WWII, there was a brief flourishing of magazine illustration - both editorial and advertising-related - based on the American model, though the popular printed media were more and more heavily dominated by photography. Several artists made considerable illustrative and graphic design reputations for themselves in this period, including painters who exhibited regularly in the tradition of double callings established in Canada in the 1880s and 1890s: eg, Franklin Arbuckle, William Winter, J.S. Hallam, Jack Bush, Oscar Cahén and Harold Town.

The magnet of the US again attracted many of the finest talents. Unlike his ex-compatriot Doug Johnston, who reached the top of his profession in New York in the 1970s, James Hill came back to his native Toronto late in the same decade. Though less lucrative, the Canadian commercial art marketplace is also less voraciously competitive than its American cousin.

Periodical illustration has enjoyed a renaissance in the past decades, thanks to a half-dozen or so art directors who have given opportunities to a new generation of illustrators. Several of its members have taken advantage of the doors opened for them by the departure southward of their patrons and mentors and made entrées in the glossy big-circulation magazines. The precariousness of the Canadian publishing scene, as exemplified by the demise of such former venues as Liberty, Canadian Home Journal, Mayfair and Weekend Magazine, means that secure markets for quality work remain few and rates of pay are comparatively low. The highest degree of experimentation and innovation at present and likely for some time to come is to be found in the specialized field of computer graphics.

Book illustration over the past 30 years has become increasingly restricted to children's literature and school texts on the one hand, and to the limited edition livre d'artiste on the other. Among the most conspicuous names associated with the former category in the period 1950s-70s are Fred J. Finley, Selwyn Dewdney, John A. Hall, Leo Rampen, John Marden, Lewis Parker, Vernon Mould, Frank Newfeld, Carlos Marchiori, Elizabeth Cleaver and Laszlo Gal. Many of this company also authored the words they illustrated: witness R.D. Symons, Annora Brown, Illingworth Kerr, Clare Bice, James Houston, William Kurelek, Shizuke Takashima, Ian Wallace and Ann Blades.

Bice, Kerr and Kurelek are typical of the serious painters and printmakers who have made noteworthy forays into the field of book illustration in the past few decades. Others include Jean-Paul Lemieux, D.C. MacKay, Jack Shadbolt, Eric Aldwinckle, Philip Surrey, Allan Harrison, Lorne Bouchard, Saul Field, Laurence Hyde, Joe Rosenthal, Aba Bayefsky, Louis de Niverville, Dennis Burton, Tony Urquhart, Gordon Rayner, Greg Curnoe and Vera Frenkel, Paul Fournier, Charles Pachter and Glenn Priestley.

A related phenomenon is the incidence of books illustrated (and, occasionally, written) by Native Canadians, a genre that begins with Christie Harris's Raven's Cry (1966), illustrated by Bill Reid, and George Clutesi's Son of Raven, Son of Deer (1967), and continues with Norval Morrisseau's paintings for H.T. Schwartz's Windigo and Other Tales of the Ojibways (1969), Ashoona Pitseolak's Pitseolak: Pictures Out of My Life (1971), Francis Kagige's images for Prunella Johnston's Tales of Nokomis (1975), Peter Pitseolak's People from Our Side (1975) and Ruth Tulurialik's Qikaaluktut: Images of Inuit Life (1986).

Out of the tradition established by E.S. Thompson have emerged the school of so-called "wildlife artists" whose highly detailed work better fits the description of illustration than of fine art, and which has found itself between the covers of stacks of full-colour, folio-format books, most of them printed outside of Canada. The best-known of these pictorial naturalists are the ornithological painters J. Fenwick Lansdowne and T.M. Shortt, followed by George McLean, Glen Loates, Robert Bateman and their numerous imitators.

Today few, if any, Canadian illustrators can make a living from book or editorial work exclusively. Illustration as a craft and as an art survives because of the love and respect for it shown by a handful of publishers, authors, critics, historians, collectors, readers and the artists who keep the flame alive.

Also abetting this advance are such factors as:

• the growing numbers of publishers of illustrated children's books, such as Annick Books, Groundwood Books, Kids Can Press, Scholastic Canada Ltd and Tundra Books;

• showcases like the Milk International Festival for Children, the Word on the Street annual literary event held simultaneously on Toronto's Queen Street and streets in Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Halifax, and the various other provincial book fairs;

• facilities like the Canadian Children's Book Centre (which publishes Children's Book News) and the Toronto Public Library's Boys' and Girls' House, which in the Osborne and Lillian H. Smith Collections boasts one of the world's largest gatherings of children's books;

• the publication of such references as Sheila Egoff and Judith Saltman's The New Republic of Childhood (1990), Meet Canadian Authors and Illustrators and the CANSCAIP Companion;

• the appearance of agents specializing in illustrators as well as writers;

• the picture sections of the various awards that honour contributions to children's literature, such as the Mr Christie Award, the Smarties Prize, the Elizabeth Cleaver Award, the Ruth Schwartz Award, the Vicky Metcalf Award, the IODE Book Award, the Ontario Library Association's Silver Birch Award, the Canadian Library Association's Book of the Year Award, the R. Ross Arnett Award for Children's Literature, the McNally Robinson Award, and, perhaps most important, the Canada Council-administered Governor General's Awards for Children's Literature/Littérature de jeunesse (Illustration).

The first winners of the Governor General's award, introduced in 1987, were Marie-Louise Gay and Darcia Labrosse; 1988's winners were Kim LaFave and Philippe Béha; 1989's, Robin Muller and Stéphane Poulin; 1990's, Paul Morin and Pierre Pratt; 1991's, Joanne Fitzgerald and Sheldon Cohen; 1992's, Ron Lightburn and Gilles Tibo; 1993's, Mirielle Levert and Stéphane Jorisch; 1994's, Murray Kimber and Pierre Pratt; 1995's, Ludmila Zeman; 1996's, Eric Beddows; 1997's, Barbara Reid; and 1998's, Kady MacDonald Denton. The 1994 winner of the Ruth Schwartz Award, Northern Lights, The Soccer Trails, by the Inuit writer Michael Kusugak, with illustrations by Vladyana Krykorka, was selected for the Aesop Accolade List, the first time the American Folklore Society has recognized a book published outside the USA.

Another "mainstream" success is that of the Victoria, BC-based Ken Steacy, who started out as an airbrush illustrator working for corporate, editorial and comic-book clients such as Marvel Comics, then moved into the electronic realm, applying his abilities as a draughtsman to the creation of interactive CD-ROM games. In his four-part Tempus Fugit series, published by DC Comics, he performed all creative functions, including writing, artwork, lettering and colouring by airbrush, a labour-intensive process now made considerably easier by digital imaging. Steacy now writes and illustrates the Star Wars books. Calgary-born Todd MacFarlane created his cartoon character Spawn in 1992 and published it himself (rather than through a US comic book publisher); first issues sold more than a million copies. With the proceeds he created MacFarlane Toys, which is now North America's largest maker of action figures.

The animated cartoon - an increasingly politicized vehicle of expression - is another medium that has seen extraordinary advances since the advent of the MacIntosh desktop computer in 1984. Today, largely thanks to the internationally recognized computer animation course at Oakville, Ontario's Sheridan College, Canada is a net exporter of talent if not of "product" (again largely because of US control of manufacturing and distribution).

Following in the wake of the National Film Board of Canada's global success in this area are such independent or "fringe" animators as John Kricfalusi, creator of Ren and Stimpy on the Nickelodeon channel in the US, and Vancouver's Marv Newland (head of International Rocketship) and Danny Antonucci, creator of the Grunt Brothers - hard-edged, often scatological commentaries on late-twentieth-century society and TV culture.

Learning to respond creatively to the challenges presented by the "electronic canvas," multimedia and the information highway, as Oshawa's Andrew Wysotski and Toronto's Lacalamita have done, is a prerequisite for professional survival, but the love of creative, imaginative illustration in the older modes will doubtless remain strong, especially as nostalgia for what are deemed simpler and more innocent times sets in. Hence the popularity of illustrators like Mark Summers, Damian Glass, Kim LaFave, Wesley Bates and Gus Reuter, who are reviving such traditional techniques as scraperboard and wood-engraving and the hand-crafted book.

And while expressionism continues to be a popular stylistic influence (Emanuel Lopez, Paul Turgeon, Jerczy Kolasz), other historical art movements find their admirers among Canadian illustrators, whether it be the Italian Renaissance of Gerard Gauci and Ken Nutt, the turn-of-the-century academic realism of Linda Montgomery or the jazz age streamline moderne of Helen D'Souza. Eclecticism is the watchword of Canadian illustration as it approaches a new century and the radical changes in communications that await.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom