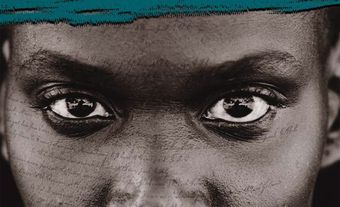

The role of Black people within the history of the fur trade is rarely considered. Black people were rarely in a position to write their own stories, so often those stories went untold. This owes to a complex set of factors including racism and limited access to literacy. Black people are also not the focus of many historical documents. However, historians have identified several Black fur traders working in different roles, and even an entire family of Black fur traders who left their mark on history.

An Overlooked History

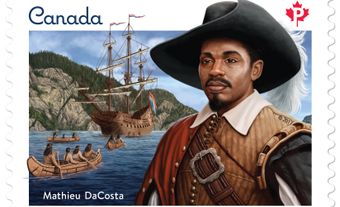

The fur trade drove Canada’s development as a colony. The presence of Black Canadians within its history, however, has been largely overlooked. In part, this is because historians’ interests have been elsewhere. But the omission has also owed to the misconception that the history of Black people in North America is mostly confined to the United States and farther south. For example, many Canadians are aware of York, the African American man who accompanied Lewis and Clark’s expedition from Missouri to the Pacific Ocean. But few can name a Black Canadian who acted in a similar capacity.

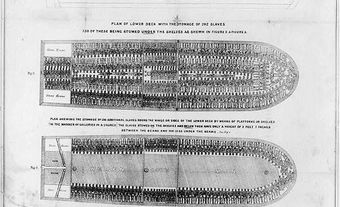

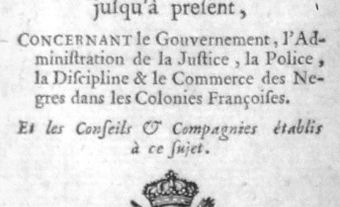

Moreover, many assume that Black history in Canada emerges from slavery in the United States. Yet, laws supporting slavery existed in Canada from the 17th to the 19th centuries. France’s Code Noir is a key example. Though it was not formally adopted in New France, it guided the actions of settlers engaged in the slave trade. It set standards for how enslaved people — both African and Indigenous — could be treated, acquired, exchanged and accounted for as property (see Enslavement of Indigenous People in Canada, Black Enslavement in Canada). The history of slavery in Canada partly shows the history of Black people engaged in or linked to the fur trade.

Roles of Black Fur Traders

The slave trade helped enrich France, England and their colonies. Enslaved people were seen as one of the many commodities that wealthy people owned. Because the fur trade was another major source of wealth, it included people who participated in the enslavement of others. Sometimes, fur traders themselves were enslavers. Some Black fur traders had been slaves, bought, for example, from trading posts with connections to slavery.

While White traders sometimes brought enslaved people on fur-trading expeditions, the master-slave power dynamic was less tenable in these contexts. This is because fur trading typically involved both isolation and close interdependence in small crews: cooperation and partnership were necessary for survival. Furthermore, without constraints on their movement, slaves would have had chances to escape. Given the greater degree of freedom to be found in the fur trade, some Black people likely even pursued the fur trade as a means of escape from slavery. Others were simply free and freely pursuing their livelihood.

Whether freely engaged or not, they were often subject to power structures that disadvantaged them compared to White traders. Typically, they worked in relatively low positions as middlemen (paddlers seated in the middle of a canoe), labourers, cooks or servants. Occasionally, they were steersmen, which was considered a skilled role (see Voyageur). But they also often served in the very important role of translator. It was common for them to know Indigenous languages because, like many frontiersmen, they married Indigenous women or grew up in mixed families ( see Métis).

There is evidence of many Black fur traders working in the industry. However, only a few are known by name and have stories that can be traced with any certainty.

Glasgow Crawford (also Glasco Crawford)

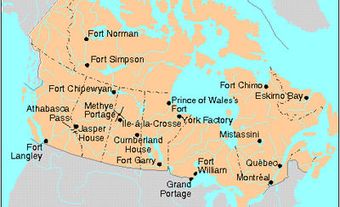

Glasgow Crawford worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) from 1818 to 1821. He was mainly a middleman but also acted as a cook. According to historian Frank Mackey, he worked in the Athabasca department (present-day Alberta and Saskatchewan) and later married a Kanyen’hekà:ka woman from Kahnawake, where the two eventually settled. During his time working for the HBC, he was involved in conflicts more than once, partly due to racist abuse, and partly due to his theft of staple items from the company store. At the same time, the HBC valued him for his language skills. He was said to speak English, French and Haudenosaunee languages fluently.

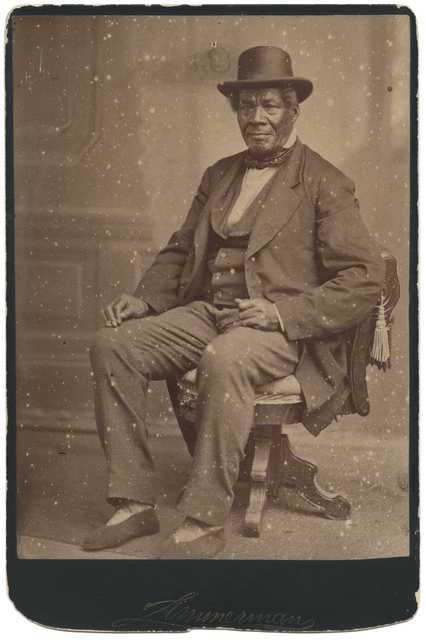

The Bonga family (also spelled Bungo, Bonza or Bongo)

The Bonga family is probably the best-known Black fur-trading family due to the number of surviving documents about them. Pierre Bonga was born in the mid- to late 1700s in the part of New France that is now Michigan. His parents, Jean and Marie-Jeanne Bonga, were enslaved people. Daniel Robertson, a British captain who was in charge of the post at Michilimackinac, may have brought Jean and Marie-Jeanne from the Caribbean or Montreal. When Robertson left his post, he also freed his slaves.

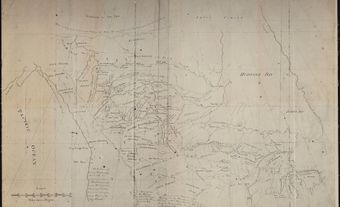

Pierre and a brother, Étienne, became fur traders, though little more is known about Étienne. Pierre was particularly active in the Red River region. He worked with the North West Company and accompanied well-known explorers such as Alexander Henry (The Younger) throughout the Pembina and Red River regions. Pierre primarily spoke French, but he could also speak Anishinaabemowin and regularly acted as a translator.

Pierre married an Ojibwe woman and had several children. Two of their sons, Stephen (also known as Étienne) and George, became fur traders like their father. Both sons were baptized and educated in Montreal. Stephen worked for the North West Company and George worked for the American Fur Company. They went on trading expeditions throughout the Great Lakes region that is now Minnesota, Wisconsin and Northern Ontario.

Stephen joined Donald McKenzie and John Rowand’s 1822 exploration of the Bow River. He is one of the first recorded Black people in the territory that would become Alberta. As an Anishinaabemowin speaker, Stephen often served as a translator and is one of the signers of the 1837 treaty at St. Peters (near Minneapolis, Minnesota). When the fur trade started to dwindle, Stephen settled in the Fond du Lac region along the St. Louis River in Minnesota and found other ways to make a living.

Bungo Township and Bungo Creek in Minnesota commemorate the Bonga family name to this day.

Joseph Lewis

Joseph Lewis worked in the fur trade in the western part of Rupert’s Land. Lewis was also among the first Black people to settle in this area. He is likely the first Black person on record in the territory that became Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom